![]()

1

The Plantation as a Social Institution

Introduction

The problem of the plantation, whose lusty revival in tropical countries we are now witnessing, is a part of the larger problem of what Teggart calls “politicization,” the process of state-making, of bringing men under new and more stringent forms of control.1 Concerning the state there are a large number of interpretations, and many explanations of classes, castes, and forms of forced labor, such as slavery, have been advanced. But there is very little in the literature of social science that might be called a theory of the plantation. Any effort to supply such a theory will face at the outset certain fundamental questions: What is a plantation? Why does the plantation arise in some areas and not in others? What is the natural history, i.e., the cycle of change, of this institution? Concerning questions of this sort, answers have come mainly from students of colonization. These students have, in general, sought to explain the plantation mainly in terms of climatic influences or causes.2

It is the thesis of this study that the plantation is to be regarded as a political institution which has a natural history very much like that of other types of political institutions as, for instance, the state. The plantation, so far as it may be regarded as a political institution, is one that exists for the purpose of bringing land into new and higher uses through the medium of an agricultural staple which is sold on the metropolitan market. The plantation arises out of settlement, out of the contact and collision of diverse racial and cultural groups on a frontier, as a means of maintaining and realizing original economic purposes. It acquires its institutional characteristics in the process of meeting and finding some sort of solutions to its most persistent problems: the problem of operating at a profit and of getting and controlling an adequate supply of cheap labor. Its purposes are industrial; its means for achieving these purposes are political. It is a political institution in so far as it introduces, or evolves, and enforces order where there has been disorder and uncertainty among individuals who have been torn out of former group relations and left disorganized and unattached. The plantation arises as the personal “possession” of the planter who is able to acquire it, to enforce his authority, and incidentally, to compose conflicts and settle individuals on the land. In the process an aristocracy and a peasantry are established with appropriate attitudes of loyalty, responsibility, and control.

Amid a multitude of details and a variety of entangled considerations of general interest the theme we seek to keep clearly before the reader is that the plantation is an incident in the conquest, settlement, and exploitation of a frontier area, and that its changes mark the changes in the frontier itself. The general process in which the plantation originates and develops is designated by Teggart as politicization.

Politicization, on its objective side, seems to denote a relative transition from a form of society in which the collective force is diffuse and whose integrating principle is consanguineous or totemic, to another in which power is usurped by, or delegated to, particular individuals, or a class of individuals, and whose unity is based upon locality. For the understanding of how human institutions have come to be as they are the importance of this transition can hardly be exaggerated. Or such was the conviction of Sir Henry Maine:

The history of political ideas begins with the assumption that kinship is the sole possible ground of community in political functions; nor is there any of those subversions of feeling, which we term emphatically revolutions, so startling and so complete as the change which is accomplished when some other principle—such as that, for instance, of local contiguity—establishes itself for the first time as the basis of common political action.3

For Teggart, the problem of politicization arose in connection with his inquiry into the proper uses of history in the study of how man and his institutions have come to be as they are, or, more abstractly, of historical events in relation to social change. It is observed that “political organization is an exceptional thing, characteristic only of certain groups, and that all peoples whatsoever have once been or still are organized on a different basis.”4 Various theories that have been proposed in explanation of the fact that political institutions are unequally distributed among the peoples of the earth are examined and rejected by Teggart. Two of these are the familiar theories of geographical and of racial determinism.5 Teggart’s point of view, as an historian, is to accept man “as given,” to leave aside all questions of innate differences, and to regard change as ensuing “upon a condition of relative fixity through the interposition of shock or disturbance induced by some exterior incident.”6 In migration is sought the major source of these shocks and disturbances.

Political institutions arise at the termini of routes of travel, at “points of pressure,” where collision and conflict have broken up kindred groups.7 Collision and conflict, in breaking up the older organization, have the effect of liberating the individual man from the customary dictation of his group “as a result of the breakdown of customary modes of action and of thought, the individual experiences a ‘release’ in aggressive self-assertion. The overexpression of individuality is one of the marked features of all epochs of change.”8 This aggressive self-assertion and individual release

has been the necessary prelude to the emergence of territorial organization and the institution of personal ownership. However far apart these elements may appear in modern life, in the beginning they are identical, for the fundamental characteristic of political organization is the attitude of personal ownership assumed by the ruler toward the land and the population over which he has gained control—an attitude expressed to this day in the phrases “my army” and “my people.” . . .

The crucial point to be observed here is that kingship and territorial organization represent simply the institutionalization of a situation which arose out of the opportunity for personal self-assertion created by the breakup of primitive organizations and it should be understood that just as the relative stability of the older units follows from the fact that every human being is born into a given group and becomes assimilated to this in speech, manners, and ideas, so, in this new organization, the status quo operates to perpetuate itself, and the mere fact of its existence becomes an argument for regarding it as ordained by some super-mundane power.9

The Plantation Defined

The plantation, as here considered, is a large landed estate, located in an area of open resources, in which social relations between diverse racial or cultural groups are based upon authority, involving the subordination of resident laborers to a planter for the purpose of producing an agricultural staple which is sold in a world market.10 In discussing the plantation we are, of course, not limiting ourselves to any one historic institution; rather we are dealing with the generic, the typical plantation. Each historic plantation area may show unique characteristics, but the above mentioned features they all hold in common. There are a number of social and economic organizations which, while closely related to the plantation, differ in one or more important respects from it. We may notice a few of these.

The manor represents a situation where economic self-sufficiency has entered the mores as something of an ideal and rent rather than profits is sought. Contrarily, the plantation depends upon the development of trade and transportation. But the manor actually has much the same history as the plantation. Both the lord and the planter exercise judicial functions and become eventually officials of the state.

The ranch is related to the plantation, but, because it produces a commodity which ordinarily can transport itself to market, it is usually located further inland than is possible for commercial agriculture without cheap transportation. The ranch also is an institution for bringing land into new and higher uses. The labor economy of the ranch, however, diverges sharply from that of the plantation at the point where it becomes possible by means of mounted laborers to manage large numbers of livestock. The cowboy, mounted, wild and free, has little in common with the routine stoop-laborers of the plantation.

The plantation differs from the so-called large power farm, such as is devoted to wheat cultivation on the Great Plains, by the presence of operations demanding a uniform type of unskilled labor. On the plantation, machine methods for such operation either do not exist, or are uneconomic. In the absence of adequate seasonal labor it becomes necessary for the plantation to maintain sufficient labor throughout the year to meet the requirements of the peak.

The large agricultural mission is another way of bringing land into higher uses and exhibits another aspect of the process of politicization. Like the plantation it may produce staples for sale on the market, but the agricultural mission is fundamentally an institution maintained specifically for the assimilation and education of the native. Although the plantation is frequently justified as training in “regular work and healthy exercise,” we may safely say that training and education are rarely serious motives of the planter in operating a plantation. The test of plantation success or failure is the return of the investment which it gives, and the predominance of motives other than those of profit-making is sufficient to change it into some other sort of institution. The plantation governs its membership, therefore, not for the glory of God, but for the material advancement of His planters. Nevertheless, although no part of the planter’s motive, the plantation is a powerful agency of assimilation and acculturation.

The Plantation and Colonization

The history of the plantation is bound up with the discovery of new lands and the expansion of commerce, with the steamship, the railway, and other new means of transportation. It is bound up with the growth of colonies and cities, and of a world market. It is, in short, a colonial institution producing for the world market what the Germans call kolonialwaaren, i.e., sugar, spices, etc.11 Colonization is one way of extending the community’s frontier.

Students of urban institutions and areas, the slum, for instance, have found it necessary to understand each area and institution in the wider context of the entire urban community, the area over which there is competitive cooperation. Likewise the plantation, as a colonial institution, cannot adequately be understood apart from the economic and geographical coordinates which constitute the world community.

In the world-wide economic “web of life” peoples and regions maintain more or less specialized divisions of labor in an organization which is sometimes called the Great Economy. The Great Economy creates the occupational “places,” or jobs, which are relatively stable and which a succession of individuals may fill. This is one ordinate of the world community. The other is the still more stable geographical base upon which the Great Economy is overlaid. By the world community we mean that competitive and cooperative organization which is observed in the distribution of individuals, or groups of individuals, on the map, and which we seek to analyze into a system of spacial relationships between such individuals or groups of individuals. In the world community the location of institutions is seen not merely as a fact but as a problem, the problem of understanding the processes that determine their spacial position.

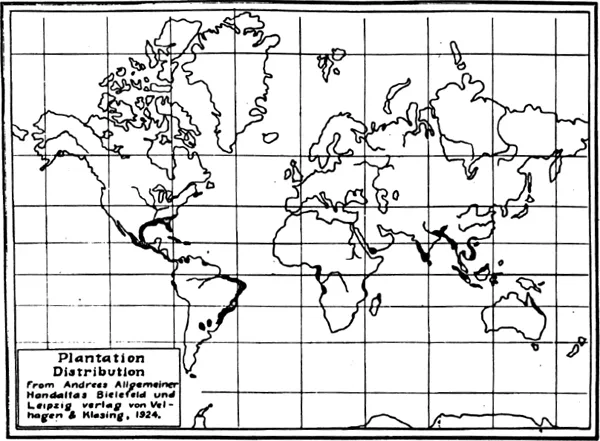

The accompanying map is intended to give some conception of the present distribution of plantations in the world community.12 Plantation areas are predominantly in tropical or semi-tropical regions forming a belt about the equator all around the world. The most absolute extent to which they are fixed on continental coasts and archipelagoes in this belt indicates their relation to cheap ocean transportation. It is only by way of the ocean that any commodity enters the world market; the world market exists, for one reason, because ocean transportation is relatively so cheap that competition becomes world-wide. It is no accident, therefore, that the islands of the East and West Indies, with easy access to cheap ocean transportation, have been among the most important centers of plantation agriculture.

The tropical and semi-tropical distribution of present plantations has suggested to certain students that the explanation of the plantation may be found in climatic influences or causes. As previously stated, such is the usual explanation of students of colonization. The work of Keller may briefly be considered as representative of this interpretation.13 Many, if not most, of the varying geographical factors influencing the form and development of colonies are, according to Keller, finally correlated with differences in climate, and climate, for all practical purposes in the study of colonization, may be broadly divided into tropical and temperate. “[A]griculture is the only important primary form of the industrial organization common to colonies of all latitudes and altitudes” and, therefore, is “the only criterion of classification of adequate generality, not to mention importance.”14 Agriculture is adjusted to climatic conditions with all variations between temperate and tropical climates. Colonies based upon temperate agriculture become farm colonies, whereas those based upon tropical agriculture are characteristically plantation colonies.

The temperate farm colony is marked by economic and administrative independence, democracy, and equality. Its unit of organization is the family, and the population is fairly well divided between the sexes. Hence there is little contact with native women and no mongrel population. The farm colony is also characterized by free labor.

The tropical plantation colony, on the other hand, presents a marked contrast to the temperate farm colony in almost every respect. “The colonists are few in number, they do not contemplate an extended stay, and are represented preponderatingly by males: the racial unit is thus the individual, not the family.”15 In consequence, relations with native women produce a mixed-blood population. The motive of the colonists is to exploit the resources of the country for the home market, but since “vital conditions do not permit of the accomplishment of plantation labors at the hands of an unacclimatized race,” laborers must be imported from other tropical regions if the natives cannot be coerced.16 “Plantation colonies have regularly been the seats of wholesale enslavement,” and the abolition of slavery leads only to various substitutes and subterfuges.17

The two opposing types of frontier agricultural organization grow out of differences in climate and in turn set up a different labor economy and a different social organization. This statement would seem to summarize Keller’s explanation of the tropical or semi-tropical distribution of plantations. The limitations of the explanation as a theory of the plantation may be pointed out.

The plantation is a frontier institution which depends upon the development of trade, and the basis of trade lies in the exchangeable differences of peoples and areas. If the basis of trade is solely the difference in degree of industrial development between frontier and market, the exploitation of resources, agricultural or mineral, may be almost entirely independent of climatic cond...