![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Early Years

As South Carolina State opened its doors in 1896, other doors were slamming shut on African Americans throughout the South and across the nation. Segregation laws mandating the separation of the races on railroad coaches, trolley cars, and steam boats, and in parks, auditoriums, and rest rooms proliferated in the aftermath of Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Black men were excluded almost entirely from the political system in South Carolina with the adoption of the 1895 constitution. Following the departure of John W. Bolts from the general assembly in 1902, there were no longer any black men serving in the state legislature. Because only qualified voters were eligible to serve on juries, very few black men and no women were summoned for jury duty.1

The epidemic of racial violence so closely identified with the South in the late nineteenth century continued unabated. One hundred and thirteen black men, four black women, and three white men were lynched in South Carolina between 1889 and 1918. On December 28, 1889, eight black men accused of killing a local merchant were forcibly removed from the Barnwell County jail and lynched. Frazier B. Baker, the newly appointed postmaster of Lake City, was killed in February 1898 by a mob of three hundred to four hundred people who did not want a black man supervising the town post office. During the Phoenix riot in Greenwood County later that year an unknown number of black men—perhaps a dozen—were slain after a white Republican candidate for Congress made an issue of black voting rights.2

Ten black men and one white man were lynched in Orangeburg County between 1880 and 1924. On January 6, 1897, a young black man, Lawrence Brown, was lynched less than three miles from the recently opened college. Brown allegedly burned a barn belonging to R. E. Wannamaker. Brown’s body was found along the railroad track near present-day State A&M Road between St. Matthews Road and Route 601 in close proximity to land S.C. State would acquire some four decades later for a campus farm. Brown’s family filed a lawsuit against Orangeburg County to recover damages, but a local judge dismissed it.3

It was in the midst of this depressing racial climate that Thomas Miller assembled a faculty and staff in Orangeburg to undertake the creation and operation of an educational institution that would serve the state’s nearly eight hundred thousand black residents. But the appearance of the buildings and grounds that had been acquired from Claflin did not impress the first students who arrived at the new college that September and October 1896. James A. Pierce, one of those students, later recalled that it was “a very unattractive place with roads running in every direction and ending up at no particular place. Deep gullies made by heavy rains were all through the center of the campus.”4

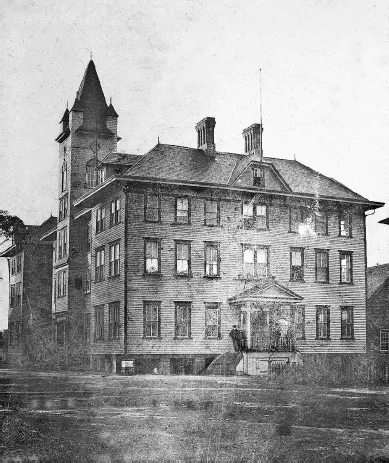

The first of three Bradham Halls was built in 1897 in part by students with timber harvested from the campus. It served as an academic building and dormitory, and it contained administrative offices. Named after one of the first members of the board of trustees, Major D. J. Bradham, it burned to the ground on November 24, 1909. Courtesy of Historical Collection, South Carolina State University

The eight-acre campus had no running water, no sewer system, and no electricity. Fenn Cottage was a six-room structure inherited from Claflin, and it needed renovations before it became the president’s residence. In the meantime Miller and his wife resided in town while their children remained with an aunt in Grahamville in Beaufort County. After Fenn was remodeled, the Miller family occupied one room that served as a bedroom, kitchen, dining room, and pantry. The five remaining rooms housed female teachers by night and were transformed into classrooms by day. For three months in 1896, twenty-five young men lived on the second floor of an eighteen-by-thirty-foot laundry building known as the Old Red Inn. It was an annex of the industrial building that had also been acquired from Claflin. For a brief time the first floor served as a chapel.5

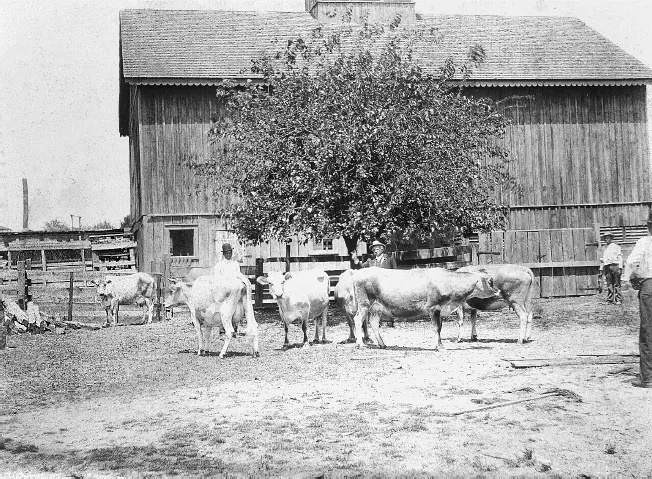

Bradham Hall was completed in early 1897. It was an impressive three-and-a-half-story structure built largely of pine and oak timber that had come from trees cut down on the campus. Miller had acquired a used sawmill, and students and faculty members contributed much of the labor in the construction of Bradham. The multipurpose facility would serve as a dormitory for men, women, and female teachers. It included a dining hall, a chapel, classrooms, a library, an accountant’s office, and President Miller’s office. The new college also had a 130-acre farm that featured a barn, two mules, a small herd of dairy cattle, and a flock of chickens.6

THE A&M MISSION AND THOMAS E. MILLER

The college was a land-grant institution that would offer instruction in agricultural and mechanical skills as well as teacher training. Because so many of the state’s black youngsters did not have access to primary and to secondary education, S.C. State would serve as a public school and a normal school during its earliest decades rather than as a bona fide college. There was a desperate need to provide basic education to a large portion of the state’s black youth. As of 1900, 53 percent of the adult black population in South Carolina was illiterate, and just 45 percent of black children between the ages of ten and fourteen were enrolled in school.7

As an A&M institution, South Carolina State would offer instruction in keeping with the models established by Samuel Chapman Armstrong in 1868 at Virginia’s Hampton Institute and by his disciple, Booker T. Washington, at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute in 1881. Students would master agricultural and vocational skills as well as a dedication to hard work, thrift, and morality that would enable them to become productive members of society. In an address at the Bamberg County Colored Fair in 1897 President Thomas Miller explained the mission of S.C. State. “The work of our college is along the industrial line. We are making educated and worthy school teachers, educated and reliable mechanics, educated, reliable and frugal farmers. We teach your sons and daughters how to care for and milk the cows, how to make gilt-edged butter, how to make cheese, what kind of fertilizer each crop needs, the natural strength and productive qualities of the various soils, and last to make a compost heap and how to take care of it. We teach them how to make a wagon, plow and hoe, how to shoe a horse and nurse him when sick. We teach your children how to keep books and typewrite, we teach your girls how to make a dress or undergarment, how to cook, wash and iron. We teach your boys how to make and run an engine, how to make and control electricity, we teach them mechanical and artistic drawing, house and sign painting.”8

Miller’s commitment to agricultural and mechanical training belied his own educational experiences and career. He was a lawyer and a politician who had a curious and intriguing upbringing. He was born in 1849 in Ferrebeeville in Beaufort District. His mother was Mary Bird, a slave with a very fair complexion and blue eyes. She was owned by Proctor Scriven, who was also Miller’s father. Scriven was stabbed to death in 1850, and Miller would then take the name of his stepfather, Richard Miller. Mary Bird died when he was nine. He attended schools for free black children in Charleston and, by his recollection, mostly raised himself.

Thomas Miller has the dubious distinction as the only person ever employed by S.C. State who wore a Confederate uniform during the Civil War. As a youngster he was employed to ride the train and deliver the Charleston Mercury to railroad stations between Charleston and Savannah. In 1864, with the Confederacy facing grave manpower shortages, he was employed at the ripe age of fifteen as assistant conductor on the railroad. With the railroad under the direct control of the Confederate government, Miller was compelled to wear the gray uniform. In early 1865 he was captured by Union troops and briefly imprisoned near Savannah. After his release he accompanied the Twenty-Fourth New York Regiment, a black unit, when they returned to their home state, where he enrolled in public school for a time in Hudson, New York.9

He attended Howard University and graduated from Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University in 1872. Then Miller enrolled in law courses at South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) during Reconstruction, when black men were admitted to that institution. He was admitted to the bar in 1875 and practiced law in Beaufort, where he had been elected school commissioner in 1872.

By education and experience, President Thomas E. Miller was a lawyer and politician. As the president of a land-grant institution, he had to familiarize himself with the campus farm and several of its four-legged residents. Notice he has his right hand extended in a “V for victory” salute. Courtesy of Historical Collection, South Carolina State University

Miller served in the state house of representatives and then the state senate from 1874 to 1882. He became chairman of the state Republican Party in 1882. He lost election to the U.S. House in 1886 but defeated William Elliott in 1888 after a prolonged electoral controversy. Miller served in the U.S. House in 1890 and 1891. He lost his bid for reelection in 1890 in another contentious election dispute. In 1892 he lost to George W. Murray, another black man, who made a campaign issue of Miller’s light complexion. Murray denigrated Miller as “Canary” because of his fair color. While continuing to practice law in Beaufort, he ran successfully for the state house of representatives in 1894, and in 1895 he was elected as one of the six black delegates to the constitutional convention in which he played such a pivotal role.10

FACULTY AND STUDENTS

With one exception the faculty that Miller assembled in 1896 lacked agricultural and mechanical training. Robert Shaw Wilkinson, a native of Charleston, was a graduate of Oberlin College. He taught at the black State University in Louisville and received a honorary Ph.D. from that institution in 1898. He would be a professor of mathematics, mechanics, and physics at S.C. State. William R. A. Palmer, who had taught at Claflin, attended Howard University and Drew Theological Seminary. He was a professor of ancient and English classics. Isaac N. Cardozo attended Oberlin and taught mental and moral science as well as pedagogics. Matthew W. Gilbert attended Benedict College and Colgate University. He taught history, political science, and modern languages.11

The only ranking faculty member in 1896 who possessed agricultural training was John Wesley Hoffman, who taught agriculture and agricultural chemistry. He claimed a Ph.D. and had attended Howard University, Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University), and Harvard University. Hoffman taught with Wilkinson at the State University in Louisville in the early 1890s. Nelson C. Nix was a Claflin graduate who taught mathematics. Louise Bonneau Fordham graduated from Charleston’s Avery Institute and earned a bachelor’s degree while first teaching art and drawing and then history at S.C. State. Henry P. Butler taught literature, logic, and Latin. He was a graduate of Lincoln University. In addition there were several faculty members who had little or no college education who taught many of the agricultural and industrial courses.12

More than 80 percent of the students who made their way to S.C. State in its early years came from farm families. Although by 1900 black people were amassing land at a more rapid rate than white people and by 1910 over one-quarter of black farmers cultivated their own land, most of them held small parcels. Black families owned 84.1 percent of farms between three and nine acres. But black farmers possessed only 28.6 percent of the value of all farm property in South Carolina. Still most rural black families in South Carolina did not possess even small farms. They struggled to survive as sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Poverty and not prosperity marked their lives.13

However, those young people who were able to attend S.C. State in its formative years came mostly from families who owned land and were on the upper economic margins among rural black residents. In 1904 W. T. B. Williams, who was a black field agent for the General Education Board, visited the college and reported landownership among student families. “For instance, in one class 31 out of 54 came from farms of more than 10 acres. 19 of these came from farms over 100 acres. 1 had 400 acres, 1 had [indecipherable] and 1 had 800 acres. 11 of the remainder owned homes in towns and cities.”14

The most education that most of the state’s black youngsters could aspire to—including those from land-owning families—amounted to little more than basic instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic. The chance to attend secondary school was exceedingly remote. There was not one black public high school in South Carolina in 1900. The state spent a paltry $1.30 for each black child actually attending school, and 55 percent of black children ...