![]()

SHIPWRECK AT CAPE ROMAIN

Shortly after the American Revolution, an Englishman in his early thirties, Jonathan Lucas,* was shipwrecked at Cape Romain near the Santee Delta of South Carolina. Nature’s fury could not have brought together more auspiciously on those sandy shoals a problem and its solution, for the young Englishman was destined to transform the rice industry in America.

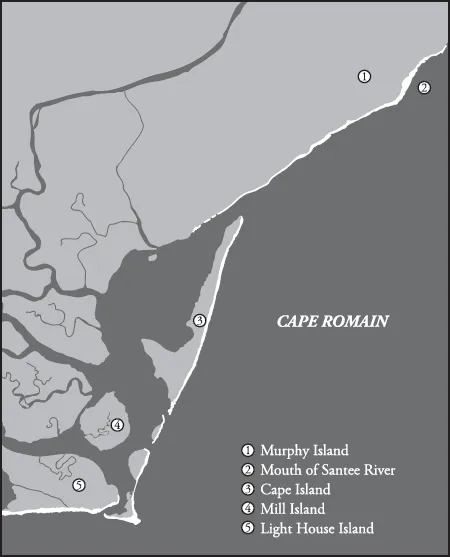

The shifting sands at Cape Romain are barrier islands, behind which lay acre after acre of cypress river swamps and marsh lands devoted to the cultivation of rice for sale on such a scale that Robert Mills (1781–1855), Charleston native and Washington Monument architect, called them gold mines of the state.† After the Revolution the tidal method of rice culture supplanted the inland swamp method, but the extremely successful yields produced a processing bottleneck that Lucas, a millwright, observed as he made his way through the delta.

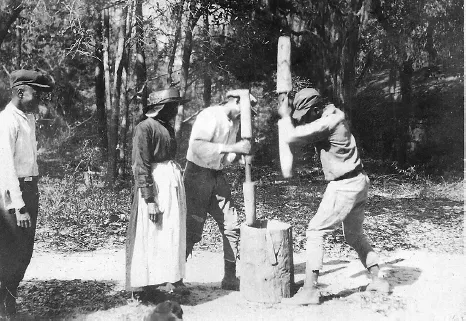

Lucas pondered the question of how to process the rice speedily as an agricultural predicament needing an industrial solution. The planters confronted a dilemma in which increasingly successful rice crops were hampered by counterproductive, nonmechanical preparation. This son of generations of successful mill owners and builders in western England watched how the grain was milled partly by hand, partly by animal power. The milling processes were tedious, destructive to the laborers, and exhausting to animal power. Lucas identified a problem in the separating of the husks from the grain: planters told him that a slave was lucky to pound out by hand, in wooden mortars with pestles, a bushel to a bushel and a half a day.

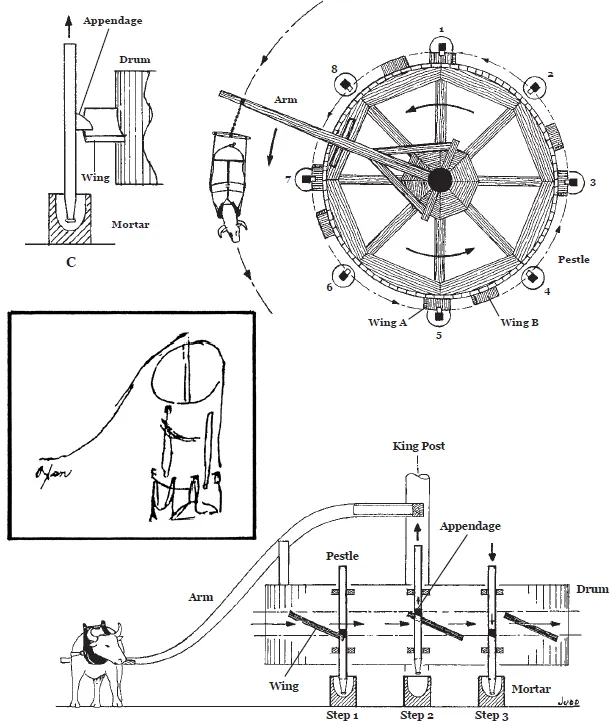

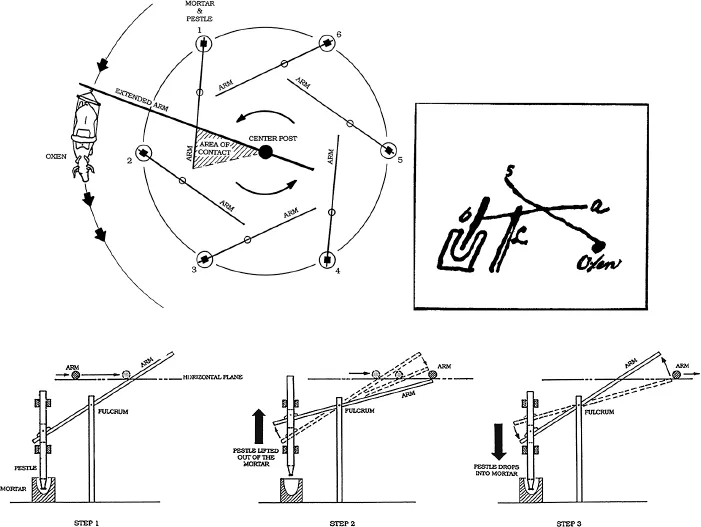

He viewed primitive rustic mills turned by animals, which revolved around pecker machines, so named because the pecker struck somewhat like a woodpecker pecking a tree. This was the simplest and probably the earliest type of rice mill used in South Carolina. The cog mill, in which upright pestles were driven by a horizontal cog wheel, was the second type. Lucas calculated that three to six barrels of rice per day was the maximum yield from these two types of animal-powered mills.*

FIG. 1. Cape Romain, St. James’ Santee Parish, South Carolina, where Jonathan Lucas was shipwrecked. Lucas Family Collections. Map adapted by Lynne Parker.

FIG. 2. Mortar and pestle. From Blakes Plantation, St. James’ Santee Parish. Photograph courtesy of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina.

FIG. 3. Cog mill drawings by William Robert Judd

In both these types of wooden mills, the rice was ground to separate the chaff from the grain. Hand-powered wind fans then blew the chaff away. Next the rice was beaten in the mills until sufficiently polished and cleaned from the flour. Afterward it sifted through different-sized wire sieves before being packed in barrels. Both the pecker and cog mills were operated by human, horse, or oxen power, with oxen preferred. No matter which system of power was utilized, milling was agonizingly slow, labor intensive, and anything but cost efficient. It was obvious that the rice planters were hampered from truly efficient crop preparation and marketing by an antiquated production process.

FIG. 4. Pecker mill drawings by William Robert Judd

John Bowman, an innovative but eccentric South Santee River rice planter, had come to the United States from Glasgow, Scotland, to speculate in Florida land but instead settled on a Georgia plantation. He later moved to St. James’ Santee Parish, where he married Sabina Lynch Cattell, daughter of Thomas Lynch and Elizabeth Allston and the widow of William Cattell. Through this marriage Bowman came into possession of Peachtree Plantation and the Lynch lands on the South Santee, which his wife inherited when her brother, Thomas Lynch Jr., signer of the Declaration of Independence, was lost at sea. Bowman underscored the plight of his fellow rice planters to Lucas and asked if he could build a machine to clean rice quicker. Lucas said he would attempt to do so.

Another account has Lucas meeting Bowman not at Bowman’s South Santee plantation but in Charleston. According to that version, Bowman, while on King Street in downtown Charleston, noticed a windmill on the gable of a wooden store where Lucas lived. He discovered that Lucas had constructed the mill and needed work. Impressed with his obvious talents, he convinced Lucas to come to Santee.

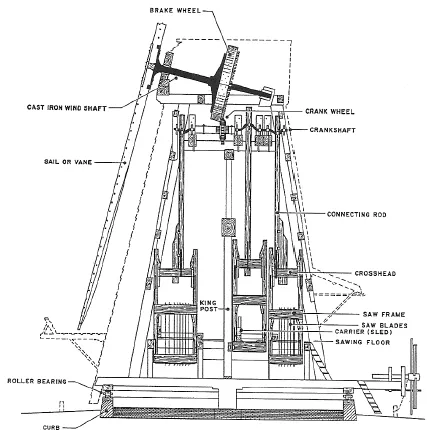

FIG. 5. Wind-powered sawmill and windmill shaft. A hypothetical reconstruction of the wind-powered sawmill erected on Mill Island, near Cape Romain, in 1793 by Jonathan Lucas I. Drawn by William Robert Judd.

It would be a few years, however, before Lucas’s mechanical genius brought this project to fruition. First he had to get established financially and make a home in Carolina for himself and his new wife, the former Ann Ashburn (1752–1838) of Whitehaven, Cumberland County, England. His first wife, Mary Cook, had died in 1783. The new couple had immigrated to America, leaving behind the five children from Lucas’s first marriage—Jonathan II (born 1775); Jane (1777); Moses (1779); John (1781); and Joseph (1783).

Jonathan Lucas moved to Hog Island to build a windmill for Bowman. Hog Island was in Charleston Harbor near Mount Pleasant. Across from Hog Island, the public road ended at the junction of Shem Creek and Hog Island Channel, where the ferry made its crossings to Charleston. While the couple was living at Hog Island, their first child, Ann, was born on December 15, 1786. The windmill probably provided power for a sawmill. The mill’s harbor side location maximized the effect of coastal breezes and winds. It was also an advantageous location for a sawmill, with nearby shipyards, the city, and the adjacent plantation country.

FIG. 6. Carleton Lodge, Cumberland, England, near Egremont. Ancient home of the Lucas family. Lucas Family Collections.

In spite of these advantages, Lucas did not stay long at Hog Island; John Bowman had not forgotten his quest to find an engineer who could solve the husking problems of rice milling. In 1787, at Bowman’s Peachtree Plantation, Lucas, with his interest in mechanics, built the first completely successful water-powered rice-pounding machine that was fed by an impounded reserve of water. Bowman’s Run was the name of the stream formed when the swamp was banked to create a reserve for the water to run Lucas’s mill. The revolutionary mill operated from a pond or reserve impounded alongside the South Santee River. Since the lowcountry was too flat for waterfalls, Lucas’s design was activated by undershot waterwheels.

Thus Lucas transformed the rice culture. He was the Eli Whitney of the rice culture, though he slightly preceded Whitney’s similar transformation of the cotton culture. These two men played pivotal roles in ushering in the agricultural revolution in the United States. Their expertise would bind the South to two labor-intensive, lucrative crops heavily dependent on slave labor, a dependence that was shattered only by the Civil War.

Previously the rice planters’ predicament was similar to that faced by short-staple cotton planters, whose slaves could in a day’s work separate by hand only a few pounds of fiber from seeds. In 1788 Carolinian John Hart had applied for a patent on a machine to gin cotton, and Georgian William Long-street had developed a steam-powered roller gin in 1792, but it was Whitney who drew on existing devices and expertise to develop an improved gin to remove the bottleneck in cotton production, just as Lucas had done for the rice culture with an improved pounding mill.*

FIG. 7. Fairfield Plantation, circa 1730), St. James’ Santee Parish. Lucas Family Collections.

Both Lucas and Whitney made revolutionary breakthroughs in relatively short periods of time. Lucas had been in South Carolina only a few years, and Whitney had arrived in Georgia at Mulberry Grove Plantation in 1792. Basically Whitney had broken the logjam in cotton ginning by adding three features to a roller gin, and Lucas, by the ingenious use of undershot waterwheels, achieved a similar triumph in the rice business.

For the next half century, Jonathan Lucas, his son and grandson of the same name, and his son William constructed his remarkable new rice mill along the “rice coast” of Georgia and South Carolina and in England, Holland, and other European sites. Lucas mills were also built in Egypt and India.

Lucas’s achievement was timely. By 1787 the rice market had stabilized following the erratic price activity after the Revolution. Also, the traditional rice marketing associations among Charleston merchants, New England merchantshippers, and British trading houses had been restored. In addition there was an increase in rice mill construction prompted by the availability of capital in South Carolina and the new technological innovations incorporated in the Lucas rice mill design. Among Lucas’s technological innovations was the construction of a rolling screen for sifting rice. He was zealous in defending his claim and brushed aside the aspirations of James Dillet, who had actually received a patent for the screen. In 1789 Dillet advertised that he had obtained a patent for a rolling sifter, and he warned planters of legal consequences for using Lucas’s mill. They were to apply to his attorney, Theodore Gaillard at 53 Meeting Street in Charleston, for a license for which they had to pay a royalty or else incur a penalty of paying a threefold price. Lucas retorted with a published article telling rice planters to ignore Dillet’s advertisement, since he, Lucas, had been the first to suggest the application of a rolling screen for sifting rice. Not only that, he had constructed a rolling screen years before Dillet received his...