eBook - ePub

Agriculture and the Confederacy

Policy, Productivity, and Power in the Civil War South

- 364 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agriculture and the Confederacy

Policy, Productivity, and Power in the Civil War South

About this book

In this comprehensive history, R. Douglas Hurt traces the decline and fall of agriculture in the Confederate States of America. The backbone of the southern economy, agriculture was a source of power that southerners believed would ensure their independence. But, season by season and year by year, Hurt convincingly shows how the disintegration of southern agriculture led to the decline of the Confederacy’s military, economic, and political power. He examines regional variations in the Eastern and Western Confederacy, linking the fates of individual crops and different modes of farming and planting to the wider story. After a dismal harvest in late 1864, southerners — faced with hunger and privation throughout the region — ransacked farms in the Shenandoah Valley and pillaged plantations in the Carolinas and the Mississippi Delta, they finally realized that their agricultural power, and their government itself, had failed. Hurt shows how this ultimate lost harvest had repercussions that lasted well beyond the end of the Civil War.

Assessing agriculture in its economic, political, social, and environmental contexts, Hurt sheds new light on the fate of the Confederacy from the optimism of secession to the reality of collapse.

Assessing agriculture in its economic, political, social, and environmental contexts, Hurt sheds new light on the fate of the Confederacy from the optimism of secession to the reality of collapse.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agriculture and the Confederacy by R. Douglas Hurt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: Southern Optimism

“The year opens full of troubles to the once United States,” wrote an Alabama farmer. As the fateful year of 1861 began, many southerners worried about the possibilities of war and disunion and anxiously awaited the course of events. Farmers hoped for the best politically but feared the worst as the South moved irrepressibly toward civil war. In Virginia the new year brought sunshine and snow, the first brightening the spirit and the second bringing soil moisture for the spring crops. Farmers considered both a good omen. Across the South as they went about the rhythm of the season, killing hogs, packing pork, making bacon, splitting fence rails, and stripping tobacco, agricultural life differed little from the past. Daniel W. Cobb, a farmer and slave owner in Southampton County, Virginia, had his hands working in the fields cutting corn and cotton stalks and burning brush along the ditches and fences to prepare his land for plowing and planting and to improve its appearance. His bondsmen thrashed cowpeas for seed, built fences, and plowed while slave women followed planting cotton and corn. In mid-January he sold 3,735 pounds of cotton from his fall crop for 11 cents per pound, 2 cents less than the average price of 13 cents on the New York market, but a consistently low price in this range since the mid-1820s, which scarcely paid his expenses. Cobb did not expect the price to rise soon.1

Overall, however, farmers and planters remained optimistic. They considered agriculture another form of southern power that would command national and international respect and recognition if war could not be averted. The creation of a new nation would be good for agriculture. In January one southerner wrote, “The absurdity of our importing Hay from Maine, Irish potatoes from Nova Scotia, Apples from Massachusetts, Butter and Cheese from New York; Flour and Pork from Ohio, and Beef from Illinois, is apparent at a glance. . . . Let us at least show the world that we are AGRICULTURALLY INDEPENDENT.” War would mean an end to dependency on northern food supplies. Agriculture and its product, food, would help win the war.2

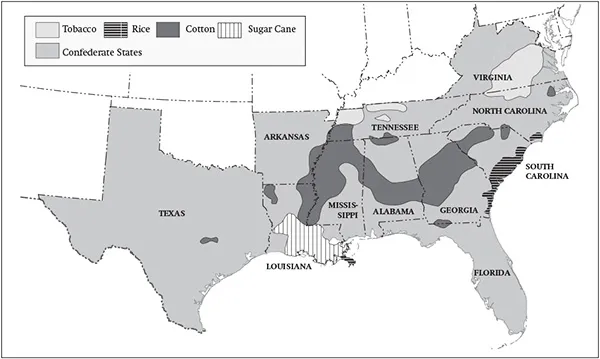

MAP 1. Major Crops of the Confederate States of America, 1861. Map prepared by Kayla M. Flamm.

In New Orleans, 217,834 bales of cotton awaited shipment and prices ranged from 7 1/2 cents to 11 1/2 cents per pound, and dealers and shippers conducted “considerable business.” A thousand hogsheads of sugar, 1,500 barrels of molasses, and 13,743 hogsheads of tobacco also awaited loading on the ships moored along the landing. Ample supplies of corn and flour and some 2,400 sacks of oats had arrived from St. Louis, all offered at good prices for merchants and farmers. In Jefferson City, Texas, cattle sold for $14 to $35 per head. Nearly wild or “piney woods hogs” brought 5 cents per pound while hogs fattened with corn sold for 6 1/2 to 7 1/2 cents per pound. Overall, agricultural prices remained consistent with the previous year (see Appendix), but the volume of sales brought money into merchants’ and farmers’ pockets.3

Agricultural abundance, not scarcity, seemed only a niggling problem. A report from Texas indicated that the “prairies swarm with fat beeves,” and cattlemen worried about declining prices from oversupply. Even so, good rains “cheered” Texas farmers and planters who prepared to seed cotton and looked forward to an “abundant harvest” of wheat. In February and March, Mississippi planter James Allen had ten plows and twenty-four mules breaking ground for corn and cotton, and his field hands followed with hoes and bags of seed. In all, they planted 220 acres of corn and 566 acres of cotton. For Allen and planters like him, the spring of 1861 seemed a time for business as usual.4

Yet, while spring brought another planting season, it now had a new urgency because nearly everyone across the South sensed the certainty of war, and southerners were optimistic about their prospects on the battlefield. Committed farmers and planters dedicated to increasing the production of grain, vegetables, meat, and fodder in a bountiful land would feed the armies while meeting the food needs of the civilian population. Southerners treated rumors that the North would win any war between the sections by starving them into submission as ludicrous. One Texan spoke for all southerners when he said, “If we make plenty to eat, both breadstuffs and meat, we cannot suffer.” The South could not lose.5

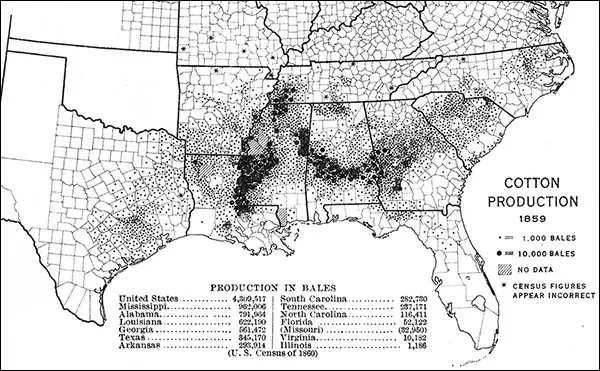

By early March, a little more than a month before P. G. T. Beauregard’s artillery fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston’s harbor, the record-breaking cotton crop of 1860 had been tallied. Everyone agreed that it had been “extraordinary,” with 4,675,000 bales picked, including 52,413 bales of long-staple Sea Island cotton that averaged 33 cents per pound for $118 per 350-pound bale, a total value alone of $6,184,754. British and European manufacturers of fine lace and muslin purchased virtually the entire Sea Island crop, as they had during previous years. Short-staple cotton averaged 11 cents per pound, a low but necessarily acceptable price given the lack of alternatives. In Atlanta yellow corn brought 90 cents per bushel and white corn a nickel more, but on the Richmond market corn sold for as low as 60 cents per bushel and cotton 9 to 12 1/2 cents per pound, while wheat brought from $1.35 to $1.55 per bushel—prices little changed from the past few months. Agricultural and food prices soon would vary widely across the South depending on crop conditions, transportation, supply, hoarding, and speculation as well as military activities and the vagaries of the weather.6

On April 12, the day of the southern attack on Fort Sumter, agricultural prices held firm. In Mississippi, planter Robert B. Alexander reported that people in town greeted the news with “great rejoicing.” Few if any farmers or consumers thought about panic buying or hoarding, which always increased farm prices in wartime. A week later agricultural prices remained steady or increased slightly except for a decline in tobacco attributed to “a want of confidence in buyers to purchase in the present unsettled condition of the country,” as sales lagged on the Richmond market. “There is little or nothing doing,” one observer reported, “owing to the excitement prevailing throughout the country.” At the same time, 1,250 bales of cotton sold in New Orleans in a single day, with the price increasing to 12 cents per pound. Southerners, however, felt secure knowing that their farms produced abundant food and fiber while reports circulated from Washington, D.C., that the city suffered from a “great scarcity” of corn and other provisions. No one feared that the food supply would fail for soldiers or citizens. One Georgian contended, “We can feed our army twelve months without buying a dollar’s worth.”7

Others, however, saw the looming danger of a long war. A Union blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, closure of the Mississippi River, and the presence of northern armies stifling agricultural trade would end any southern reliance on northern breadstuffs, forage, and livestock to feed urban and slave populations. Northern flour, packed pork, butter, eggs, hay, mules, horses, and farm equipment that southerners relied upon to help meet their food needs would no longer move south, and Confederates would suffer from this loss of trade. Patriotic optimism about the power of Confederate agriculture could change sharply from theory to reality. One Virginian urged farmers and planters to seed large crops because “we must depend on ourselves, and may have no other source of supply but our own soil.” He foresaw high prices for “everything eatable,” during the next twelve to eighteen months. His prediction proved true, but he underestimated the duration of the war. Even so, Virginians could see a bit of the future based on escalating food prices resulting from fears of a blockade. Those who had money and access to food began stocking supplies, an act that some called senseless hoarding.8

Still, the spring crops looked more than encouraging. Georgia and Alabama farmers anticipated an “abundant” wheat crop and admired “good stands of corn.” One Texan remarked that “the wheat crop is very promising; times getting a little easier.” Across the South “unusual quantities of grain” had been planted. In middle Tennessee farmers anticipated the best wheat crop since 1855, while Arkansas farmers considered it the largest crop in acreage and the best quality ever planted. In Tennessee the General Assembly asked farmers “to devote the breadth of arable land in the State to the culture of grain and grass.” Many southerners were uncertain whether northerners and international traders would obey the impending blockade of the coasts and rivers. Northern pork, grain, and other agricultural products might still reach southern markets. But southerners also believed that “hereafter our supplies will be raised at home.” The southern agricultural landscape could meet all military and civilian needs with proper development and adjustment, such as planting cotton lands with corn. Some Virginia observers even considered the early blockade of the James River beneficial because the strawberry crop stayed home rather than heading to traditional northern markets, and Virginians enjoyed the “luxury” of a plentiful crop. One Georgian reported that the North could never starve the South into submission, and remarked that if the northerners were not careful they would be “on their knees to us for bread.”9

On April 29, President Jefferson Davis informed the Congress in Montgomery that “a bounteous Providence cheers us with the promise of abundant crops. The fields of grain which will within a few weeks be ready for the sickle give assurance of the amplest supply of food for man; whilst the corn, cotton, and other staple productions of our soil afford abundant proof that up to this period the season has been propitious.” When Virginia governor John Letcher issued a proclamation prohibiting the export of flour to northern cities, southerners believed that northerners would pay a high price in hunger for their folly of driving the South from the Union.10

One observer cautioned that “this revolution will cost us some sacrifice,” but in the heady days of spring, optimism prevailed over such views amid the excitement of war. Few planters, farmers, or other southerners with independence on their minds saw a “dark uncertain future” or the possibility of anything but better days once freed from northern oppression. Yet cautiousness became recognizable by late April. One Georgian observed, “No one is speculating in land, or negroes, or any other species of property.” Farmers paid their debts and took an optimistic but wait-and-see approach to the future. In the meantime, they planted more corn. Agricultural advisers who spoke through the newspapers urged farmers to plant corn because the grain and meat trade with the Northwest via the Mississippi River would be cut off by northern armies. At the same time, Confederate soldiers would require great quantities of meat. The result would be high prices for corn, pork, and beef. “Everything that can be eaten will bring high prices and ready cash,” one contemporary noted, and he urged farm families to raise chickens and turkeys and to make butter because those commodities, too, would produce good profits. Southern farmers could be prosperous and patriotic. From Louisiana came the boast that the South could produce all of the breadstuffs, beef, and pork that it needed. Agriculturally speaking, the South was already independent.11

By May the corn crop began to sprout in Virginia, and rice and cotton broke through the soil in the Carolinas, leading one observer to report that the “vast” cotton fields in South Carolina had mostly been planted in corn. By mid-May the Georgia wheat crop neared its harvest, and the corn crop had begun to silk and tassel. Southerners remained convinced that the region’s agricultural capacity would prevail, so rich were the lands, so productive were the plantations and farms, and so committed were farmers across the South to meeting civilian and military needs for the war effort. While some realized that the times were now “critical,” they had enough confidence in the Confederate army and their own productive ability to continue planting cotton even though the Union blockade and Confederate policy closed all but a few domestic markets. Cotton had always meant consistent, dependable money in the bank, and even when southerners needed corn, wheat, pork, beef, and other agricultural products, many farmers and planters would not totally abandon this crop.12

In late May, Union forces gave no sign that they possessed the organization, strength, and leadership to bring a quick end to the war. Although General George B. McClellan issued overblown reports about his success against Confederate forces near Grafton and Beverly in western Virginia, few southerners worried about a northern invasion, which, they believed, their armies would squelch in a heartbeat. While McClellan drafted reports to enhance his career, Virginia farmers sold more cattle on the Richmond market than the butchers needed; the price declined to $4.25 per hundredweight, and the demand for hogs remained limited at $.07 per pound. In North Carolina, Piedmont farmers received 12 1/2 cents per pound for their bacon, a good price not driven by shortage. In Tennessee, beef brought an acceptable $.05 per pound, while eggs sold for $.20 a dozen, chickens $.15 each, and butter $.15 per pound. Farmers marketed hay for $1 per hundredweight. In Jefferson County, Mississippi, one farmer reported that the corn and sweet potato crops looked “good” and the cotton “tolerable well.” Mississippi farmers continued to sell corn at $1 per bushel, pork at $26, and flour at $12 per barrel respectively. Abundance seemed normal and certain, and food and agricultural prices consistent and reasonable. A bountiful agricultural sector would ensure independence and enable southerners to “combat tyranny to the bitter end.” Reports of Yankee soldiers shooting cattle, stealing horses, destroying wheat crops, and impressing slaves in attacks from Hampton to Warwick Court House in Virginia caused less concern for the losses to the farmers who experienced the raids than anger about the “brute force” levied against civilians.13

By May the blockade of the Mississippi River had halted shipments of northern flour and corn, and these provisions had become scarce in some locations, increasing prices. Soon flour brought $15 per barrel and corn $2.50 per bushel in Hardin County, Texas. Spring rains, however, gave farmers the confidence that they would soon harvest a three-year surplus of wheat. Despite the annoyance of the blockade, southern farmers and planters considered themselves the chosen people of God, who gave them signs of his blessings. After a good and timely rain, one Tennessee farmer wrote, “Providence has smiled on us, has thwarted the designs of a sectional majority in their intentions of starving the southern people into submission.” The agriculture of the Confederacy was too powerful for that outcome. Texas optimists also considered the blockade beneficial to farmers who sold their wheat to local millers, who in turn hauled flour to the coast, where residents now ate bread made from wheat raised in Texas instead of flour from Illinois. “Hurrah for the blockade!” one Texan wrote. “Nobody hurt.” Another contended that if farmers learned to provide their own seed potatoes and garden seeds, they could become even more independent of the North. In this sense the blockade could be “truly a blessing to Texas, ultimately.”14 southerners knew that cotton was “King” for their economy. They also believed that it gave them considerable diplomatic leverage, even power. From the plantations and farms came “white gold,” which created a global network of trade and European dependence on southern agriculture. By 1860 slaves cultivated approximately two-thirds of the world’s cotton in the South. William Lowndes Yancey, a “fire-eater” secessionist from Georgia, had told northerners not long before the South declared independence that “England needs our cotton and must have it.” Southerners intended to pursue a free, international trade policy that would serve its diplomatic, political, and economic interests, but when President Lincoln imposed a blockade on southern trade after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the Confederate Congress retaliated by prohibiting trade with the North and by prohibiting the export of cotton except through Confederate ports or Matamoros, Mexico. The threat of a complete southern embargo of its cotton became clear. The Charleston Mercury asserted to Great Britain, “The cards are in our hands and we intend to play them out to the bankruptcy of every cotton factory in Great Britain and France or the acknowledgment of our independence.”15

MAP 2. Cotton Production, 1859. From O. C. Stein and O. E. Baker, Atlas of American Agriculture, part V, section A: Cotton. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918.

The British proclamation of neutrality worried Lincoln and his advisers because, according to international law, such a declaration permitted trade with the Confederacy. Trade would prolong the war, during which time British cotton reserves might become depleted, forcing Britain to break the Union blockade to ge...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Agriculture and the Confederacy

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Southern Optimism

- Chapter Two: Confederate Apprehension

- Chapter Three: Western Troubles

- Chapter Four: Eastern Realities

- Chapter Five: Western Losses

- Chapter Six: Eastern Hard Times

- Chapter Seven: Western Collapse

- Chapter Eight: Last Things

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index