![]()

Part 1: Collapse, 1838–1859

The Vodou gods have charged me to convey to Jamaica a few emigrants from Jacmel. . . . This is a different story.

—René Depestre, Hadriana dans tous mes rêves, 1988

![]()

One: The Opportunity of Freedom

George William Gordon had the future of Jamaica uppermost in his thoughts when he arrived for a special meeting at the Half Way Tree courthouse in the parish of St. Andrew. On that morning in August 1842, Gordon—a merchant and colored representative of the St. Andrew vestry—and the men who preceded him through the heavy doors of the courthouse hoped for new opportunities for Jamaica. They came ready to take action on an issue that had occupied them for four years: the opening of unrestricted trade and communication between Haiti and Jamaica.

Commercial relations and regular travel between the two close neighbors had been prohibited for decades owing to their radically opposite positions: Haiti was a free nation; Jamaica was up to August 1838 a slave colony. It was perhaps not coincidental that the meeting took place on the fourth anniversary of full freedom in the colony.

Freedom promised to end many things. For the collection of men in the hot Half Way Tree courthouse, one of the benefits of emancipation should be the removal of restrictions against communication with Haiti. It was an esteemed group. Along with George William Gordon was his white father, Joseph Gordon, custos (short for custos rotulorum, the principal Justice of the Peace and Keeper of the Rolls of Justices of the Peace) of the parish, member of the colonial Assembly, planter, and estate attorney, who was called to chair the meeting. The gathering was rounded out with several magistrates and businessmen. In his opening remarks, Joseph Gordon noted that a number of “respectable gentlemen” from the parish had requested the special meeting, the purpose of which was to draft a formal supplication to Queen Victoria that Jamaican ports be opened to “unrestricted intercourse” between the two islands. After decades of formal separation, Gordon averred, the moment had long arrived for a “more social footing with a neighboring island.”1 The opening of the ports would allow for a flow of people and commodities back and forth. The “respectable gentlemen” argued strongly that this sort of exchange could only redound positively to the economic development of each island as they both headed toward an uncertain future following the decline of their once wealthy sugar industries. But Haiti had shown signs of economic recovery. Far from being an economic failure, the republic continued an active export trade, and there was the possibility for greater development. Mr. Wilson, a member of the committee who had recently visited Haiti, presented hard evidence. The meeting listened keenly to Wilson’s observations about Haiti’s potential. There was “plenty of mahogany” that could be traded for profit in Jamaica. In Haiti, corn was “little used,” and direct trade would encourage cultivation of the crop in Jamaica. There were also cattle and ground provisions aplenty in Haiti that could be sold and transported cheaply to Jamaica. Jamaica in return could supply Haiti with dry goods. Wilson’s report affirmed the hopes of the merchants of the great benefits to be achieved by closer ties with Haiti in the midst of increasing economic challenges in the sugar sector.

After a unanimous vote, a petition was drafted, signed by Joseph Gordon, and later sent to the queen. The confidence of its drafters in the necessity of Haitian and Jamaican contact was apparent in every line: “Having now nothing to dread but contemplating the promotion of our colonial prosperity, it appears to us, your Majesty’s memorialists, that industry and commercial enterprise will be increased by a free intercourse with a country the resources of which are very considerable—that by a direct and regular trade with that island our people will not merely augment their own welfare and happiness, but contribute in a proportionate ratio to the financial resources of the Mother Country.” Although the language of the petition was overlaid in fraternal rhetoric, commercial motives were central. Jamaica’s economy was unsteady, and anxiety over the fate of its major crops was palpable. A consistent reduction in sugar output, the island’s main staple export, threatened Jamaica’s once privileged position. Haiti, a republic more than double the size of Jamaica, could provide the sort of boon that Jamaican commerce needed. “Suspicion has happily given way to confidence,” the petition continued, “and even the former opposers of this measure admit that the interests of Haiti and Jamaica will be promoted, and the capital of this island be directed into a substantial and legitimate channel.”2

The men in the Half Way Tree courthouse—in the main members of a rising brown political class—were resolute on the advantages of greater contact with Haiti. But the weakening plantocracy remained skeptical as to what “unrestricted intercourse” could mean for Jamaica. In 1842 Haiti was a stable nation with obvious potential. It was also a republic birthed in a revolution led by ex-slaves. The difference of this experience from Jamaica’s was the foundation for the restricted contact in the first place. In Haiti the reasons were always clear: Haiti, a free country, would not treat with or consume products grown in the slave colony of Jamaica. For Jamaica, panicked planters feared that free movement of Haitians might lead to the adoption of radical ideas in Britain’s premier West Indian colony. This trepidation remained among the plantocracy in 1842 even as Jamaica, now a land of freedpeople, was undergoing profound transformation.

The Colony by 1842

Fear lay at the center of slavery. The captives on the plantations feared daily torture by the planters; the planters feared violent retaliation by the enslaved, who vastly outnumbered them. In Jamaica fear was acute. After the 1791 outbreak of the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue and the achievement of Haitian independence in 1804, fear of a similar occurrence in Jamaica kept the planters on high alert. Unusually large numbers of British troops were stationed in Jamaica between the 1790s and 1815. Their presence was an obvious deterrent to armed insurrection and slave rebellion.3 The most important organized rebellion against slavery in Jamaica following the Haitian Revolution occurred in 1831, after a recession in troop deployment. The event was recorded by contemporaries as “the Baptist War,” and by history as the Christmas Rebellion. Two days after Christmas a group of enslaved blacks in the western parish of St. James were led by a black Baptist preacher, Sam Sharpe. “Daddy” Sharpe and his rebels torched parts of the plantations in areas such as Leogan (named after the Haitian town of Léogâne), Blue Hole, and Content, before the rebellion crossed into neighboring parishes of Trelawny, Hanover, St. Elizabeth, and Westmoreland.

The motive for the insurrection was the false belief that freedom had been granted by the queen but withheld by the planters. The rebellion lasted ten days. After more than 200 plantations were damaged, the insurrection was crushed by the army. The loss in property damage was extensive. The human cost was devastating: more than 500 blacks were killed, most as punishment after the event. The Baptist and Wesleyan missionaries on the island were also blamed for the uprising and victimized in its aftermath. The planter elite arrested some of the missionary preachers, including the popular William Knibb, and launched an assault on the non-Conformist churches. The result was the destruction of fourteen Baptist and six Wesleyan chapels. The leaders of the Baptist and Wesleyan missions that survived returned to England, where they provided gripping testimony to Parliament on the disturbance and the horrors of slavery.

Metropolitan support for immediate abolition was profound. British newspapers, churches, and civic organizations passionately advanced the abolitionist cause. James Phillippo, a prominent Baptist leader in Jamaica, wrote about the power of this popular support after the rebellion, which pushed forth that “liberty, immediate and unconditional, the birth-right of every man, should be at once enjoyed by Africans and their descendants, throughout the British dominions, equally with other subjects of the realm.” Two years later some of the freedom that Sam Sharpe and his followers believed to have been granted, then denied, became real when the British Parliament passed a bill declaring that slavery was “unlawful throughout the British colonies” and that “all and every one” under six years old and born after 1834 were free.4

For Jamaica the end of slavery was only hastened by the Christmas Rebellion. The course of abolition began much earlier in fact, even before the Haitian Revolution. In the last quarter of the eighteenth century and especially after the U.S. War of Independence, a complex and often contradictory antislavery movement grew slowly in England and eventually developed into a crusade that spread across Europe and the United States. This vast social revolution pulled together a disparate group of reformers and petitioners with various motives for supporting the ending of the centuries-old institution of Atlantic slavery. Abolitionism undermined the Jamaican planter class, which became a symbol of decadence, abuse, and licentiousness. By the early nineteenth century, the movement had matured tremendously and gained popular and political support in England. The abolition of the slave trade in 1807 was its first victory, and with the Slave Emancipation Bill in 1834—significantly thirty years after Haitian independence when the fear of its violent spread had reduced—it achieved its greatest success.5

The transition to freedom in Jamaica was gradual. “Full freedom” for all men, women, and children did not arrive until August 1838, four years after an intermediary period of unfree labor in a system of apprenticeship. Apprenticeship was prima facie an effort toward the smooth transition in the colony to the revolutionary change of emancipation, a period of adjustment for both planters and freedpeople. The benefits were largely to the planters. Apprenticeship provided a safety valve for those who feared a brutal retaliation by the freedpeople if complete freedom was awarded. In addition to continued—though limited—unpaid labor until 1838, the planters across the British Empire were awarded £20 million as compensation for the loss of their human property, but the freedpeople received no restitution for their years of enslavement.6 For the apprentices the system was meant as a transition to life outside slavery. The administration of the system was supervised by stipendiary magistrates, appointees of the Colonial Office, charged with preparing the apprentices for full freedom.

Apprenticeship was undermined by problems in labor relations between the apprentices and the planters. Rather than prepare for the radical adjustment toward free wage labor and the expected reduction in available workers, planters used the opportunity to extract as much from their apprentices as they could. The system was without merit. Production levels did not rise appreciably. Even worse, change in status did little to improve treatment on the plantations, and apprentices suffered brutal conditions and punishment.

Two British Quakers from Birmingham, Joseph Sturge and Thomas Harvey, visited Jamaica in 1837 and reported on the abuse of apprentices on the plantations and the use of the treadmill in the island’s prisons, practices eventually outlawed in 1840. The apprentices responded to the system’s failure by asserting their own agency in negotiating, as far as they could, the conditions of their labor. This foreshadowed things to come.7

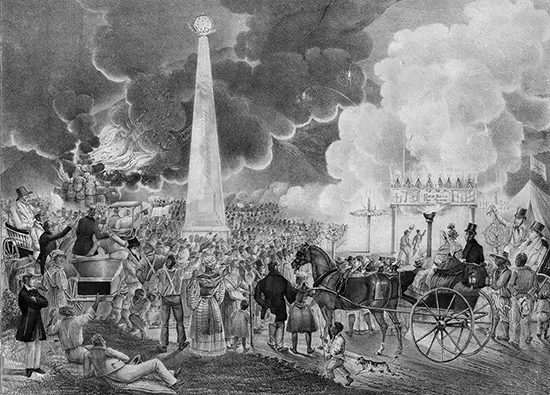

But apprenticeship was also terminal. When it ended on the morning of 1 August 1838 people across Jamaica were jubilant. On that day more than 300,000 people became free citizens equal in law to all other Crown subjects on the island. “One, two, t[h]ree, All de same; Black, white, brown, all de same, all de same,” was one of several popular refrains chanted in the streets. Thousands of freedpeople spent the morning in churches, “crowded almost to suffocation,” according to one witness. In Spanish Town, the capital of Jamaica, banners, flags, and a wreath of laurels were part of the elaborate decorations that captured the power of the event with inscriptions: “Slavery is no more,” “Freedom’s come.” Other inscriptions were writ across flags handed out to the gathering crowds—“The 1st of August, 1838, never to be forgotten through all generations”; “England, land of liberty, of light, of life”; “Am I not a man and a brother?”—as mementos of the overwhelming effect of liberation.8 At a large pageant in Kingston, a prostrate figure dramatically represented the columns of justice and freedom raising an emancipated person in the shadow of Britannia donned with the cap of liberty.9 The celebrations went beyond Jamaica’s shores to the United States and Haiti.10 Jamaica had now joined Haiti as a postslavery society.

A. Duperly lithograph of emancipation celebrations at the race course in Kingston, 2 August 1838. Courtesy of the National Library of Jamaica.

The 1838 celebrations stretched on for days, but it would take much longer for the full impact of freedom to resonate. The freedpeople appeared to grasp the value of their freedom far better than the planters or abolitionists had expected. In spite of the attempts of the transitory apprenticeship years, the planters were not fully prepared for what followed. The freedpeople devoted their attention not to estate labor on major staples, sugar and coffee, but to the cultivation of their own food crops, a practice that had its genesis in slavery. The cultivation of provision grounds and the new market for produce in the postemancipation era of wage labor led many freedpeople away from the estates to work on other properties. Attempts by the planters to keep their laborers dependent on the estates with high rents failed. Disputes and gradual movement away from the estates followed.11

Demographic change altered the island’s landscape. The thick cluster of mountains in the cool, verdant interior and those scattered across its principal coasts became sites of mushroom communities of small freeholders. Thousands of acres of land were taken up by free settlers. Without provisions from the Crown or the colonial Assembly, freedpeople built their own villages independently or with the assistance of Baptist missionaries, who remained a preeminent source of religious and practical support. By 1842 there were more than 100 free villages in Jamaica.

In the lowlands below were the sugar estates, vast unbroken tracts of canefields that consumed much of the rural scenery in every parish save Kingston. By 1842 they were beginning to show signs of degeneration. In the western parishes some of the estates damaged in the Christmas Rebellion were partially overgrown with their works still in ruins a decade later.12 In an effort to attend to labor shortages on the estates, planters began importing indentured immigrant laborers. In 1841 more than 1,000 liberated Africans, principally from Sierra Leone, came to the island after an unsuccessful attempt at white indentured labor.13 This experience later motivated planters to launch large-scale indentured immigration from India and China.

In these early years, though, the want of continuous labor pressured planters to briefly contemplate importing workers from places much closer, including the southern United States and neighboring Haiti. In 1842 a British special commission sent to in...