CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Region, Repertoire, and Genre

Two vignettes from my earliest fieldwork in the Chhattisgarh region of middle India stand out as interactions that set into play what became the central questions of this study. I spent the first month on the field visiting villages on the Phuljhar borderlands of Chhattisgarh in search of a fieldwork base. Realizing not all villages would be “equal” in the number of performance genres available, the festivals celebrated, and the castes represented, I planned to ask for general performance repertoires by gender, caste, and village and take these into consideration in my choice.1 Seated in the courtyard of a high-caste, Aghariya Chhattisgarhi village headman (gauṇṭiyā) in the first village I visited in September 1980, surrounded by a large crowd of household and neighborhood women, I tried out my survey strategy by rather simplistically asking “what kinds of songs they sang” (using the Hindi words gīt and gānā); drawing blank stares, I tried again, this time being more specific by asking if they sang songs at their weddings. Their categorical answer of “no” was surprising, since I had found numerous appearances of womens wedding songs (vīhā gīt) in printed collections of Chhattisgarhi folklore available in the library at the University of Wisconsin. It was only several days later that I began to realize that Chhattisgarhi usage of the word gānā (to sing), without being placed in relationship to a particular genre of song (such as vīhā gīt), is limited to male, professional singing—and this the women did not do. I realized that while I knew the Chhattisgarhi terms for “song” and “to sing,” I did not know the indigenous rules of usage for these terms; inappropriate usage had resulted in miscommunication. I did not yet know the indigenous “ways of talking” about folklore, genre, and performance.

The second vignette also began on this initial tour of potential field sites, but it reached closure only several months later. This time, the village was a primarily Oriya-speaking one. I had learned by now that I needed to be more specific in my enquiries about repertoire, so I asked the women of a high-caste Kolta family whether they sang vīhā gīt at their weddings. They enthusiastically assured me that they did: “Of course we sing them at our [hamar] weddings.” This was the village in which I eventually chose to live for four months before moving to the town of Dhamtari in Chhattisgarh’s heartland. I had already left, however, when the wedding season began five months later; and I traveled six hours by bus to return to the village for the wedding of the daughter of this same household. After a full day of ritual, beginning with the turmeric anointing (haldī lagānā) of the bride and now close to ending with her vida (ritual of farewell, sending her to her in-laws), there had not yet been a single women’s song. I reminded my friends of their earlier assertion, with what I’m sure was a note of exasperation, “I thought you said that you sang vīhā gīt at your weddings.” They laughed, and one explained, “When we said we, we didn’t mean our caste, we meant Oriya women.”

This initially frustrating fieldwork experience images the complex ways in which folklore genres help to identify, delineate and give identity to folklore groups and communities. The assertion that “we sing at our weddings” was made to me as a newcomer to the region and an outsider to the village. The speaker was identifying on a general level with the Oriya-speaking community of Chhattisgarh, even though it is women from ādivāsī (tribal) castes, and not her own, that sing these wedding songs. Close to five months later, the same speaker found it humorous that I had interpreted the “we” so specifically, by caste; however, it is probable that she would not have made such a broad identification between community and genre when speaking to me after I had lived in that same village for several months and had become more familiar with the indigenous terminologies of the system of Chhattisgarhi genres and their rules of usage.

Over the initial weeks of looking for a village in which to live and the months that followed during which I visited many other villages, my questioning regarding performance repertoires became more refined. I began to frame the questions with a phrase I had heard in many of the initial responses I had received, “Here in Chhattisgarh.” I would follow this with a question such as, “What kinds of festivals do you celebrate/observe (kyā kyā tyohār manāte hai)?” or I would give specific examples of the kinds of performance genres with which I had heard other villagers respond, such as candainī or the suā nāc. A core repertoire of genres gradually emerged from the varied responses, one that was repeatedly identified with the region Chhattisgarh. If conversations continued further or if we started to talk more specifically about one of the individual genres, the genres often began to be identified with smaller social groups (according to caste, gender, or age). The Oriya Kolta women mentioned above were not alone in identifying with Chhat-tisgarhi or Oriya genres on a sliding scale of inclusive identity, depending on the context and identities of conversational partners.

The focus of my study consolidated around this indigenously identified repertoire of Chhattisgarhi performance genres. I became interested in the repertoire as a system of genres, in its boundaries, terminologies, and internal organizing principles. As I listened to what performers and audiences talked about most when discussing or commenting on particular genres and performances, it gradually became apparent that a central organizing principle of the repertoire is the social identity of those to whom a genre “belongs”; genres are categorized on the basis of this social identity more commonly than on the basis of form or thematic content. I have used these principles of indigenous repertoire and genre as an interpretive frame through which to enter the analyses of six representative genres performed in the central plains of Chhattisgarh and in the border region of Phuljhar.

The first three genres considered in this book are female ritual traditions, and the last three are male-performed narrative genres in which female characters are central. The bounded regional repertoire of which these are a part presents to us a strikingly female-centered world. Female performers and/or characters are active and articulate and frequently challenge or defy brahminic (frequently male) expectations of gender. In this performance world, men, too, confound gender roles: a male storyteller assumes a mother’s voice in noticing the subtle early signs of her daughter s pregnancy; a male character takes on female disguise to protect himself in an all-female kingdom in which he is seemingly helpless; men appropriate a particular female genre to displace its defiant voice. This play of gender and genre in the Chhattisgarhi repertoire contributes to the construction of a particular regional cultural ethos and is key to its understanding.

Chhattisgarh as a Geographic and Historical Region

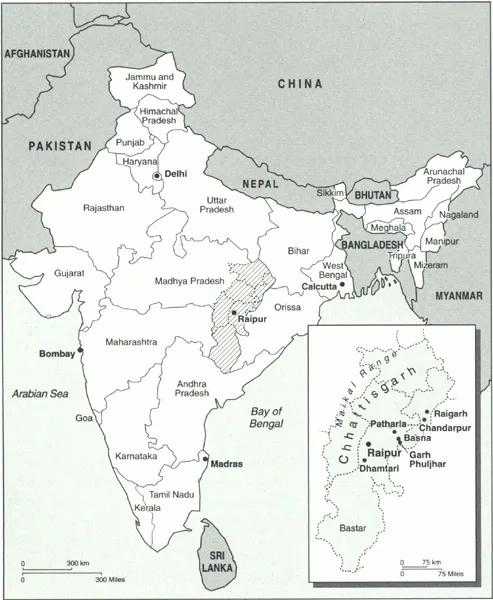

Modern Chhattisgarh is a geographic, historical, cultural, and linguistically defined region of eastern Madhya Pradesh, bordering Orissa, made up of five districts.2 My own fieldwork was confined to Raipur District, in two distinct areas, one in the district’s heartland and one on the periphery of both the district and the region. Chhattisgarh consists of a large rice-growing plain, watered by the Mahanadi River and its tributaries, and the surrounding hill regions. To the northwest, the plain is bounded by the Maikal Hills, to the west by the Satpura mountain range, to the south by the hills marking the border of Bastar, and to the east by the hills separating Chhattisgarh from the province of Orissa. Historically, the geographic barrier of these hills has helped to isolate Chhattisgarh from surrounding regions and has been a contributing factor in the development of Chhattisgarh as a politically and historically defined region. Obviously, the strength of these hills as boundaries has been minimized by modern transportation systems and popular-media channels such as radio, television, and film.

Map 1. Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh

The Chhattisgarhi plain is a heavily populated, fertile agricultural area. The construction of a canal system from the Mahanadi River has made possible double rice crops in many parts of the plain. The boundary hill areas are both less populated and less fertile, the original home of much of the tribal population of Chhattisgarh. Today, however, a high percentage of the tribal population lives in the plain and has been integrated into the local Hindu caste hierarchy, as independent castes.

Before Indian independence in 1947, the plains and hills were also differentiated on the basis of land revenue and tenure into the khalsā and zamīndārī systems, respectively (Weaver 1968:153–155). Under the khalsa system, every village and its surrounding land was controlled by a mālguzār, who was responsible to the central ruling power. The zamīndārī estates of the hill and forest regions were often as large as several hundred square miles and incorporated many villages. Each village was under the administrative power of a tḥekedār, who was responsible to the zamīndar, who in turn paid revenues to the central power. The zamīndār were often quasi-independent from the central ruling power and were themselves called kings (rājā). In 1951 the khalsā and zamīndārī systems were merged for purposes of revenue administration (Verma 1973:4).

The early history of Chhattisgarh reveals a characteristic pattern of minor kingdoms whose kings were often from junior branches of major ruling families to the north but who had gained semi-independence from centers of ruling power, partly because of the geographic distance from those centers. This history indicates that, although centrally located in middle India, Chhattisgarh was under primarily northern political influence, rather than under the domain of southern ruling powers.

The name Chhattisgarh is popularly believed to mean “the land of thirty-six forts,” chattīs meaning “thirty-six” and garḥ meaning “fort.” A. E. Nelson finds inscriptional support for this popular conception in a Khalari inscription that states that King Simhana, the second ruler of the junior Ratanpur branch, conquered the eighteen forts of the enemy. Presumably, this was half the territory ruled by the Haihayas in Daksina Kosala; therefore, the entire territory would have included thirty-six forts. But Nelson acknowledges that in all probability this was not the original derivation of the name, for the name Chhattisgarh does not appear in a single inscription. He believes the more likely derivation is from “Chedisgarh,” or “the forts of the Chedi lords,” since the Haihaya rulers were a younger branch of the Chedi dynasty who continued to be proud of the name (1909:49).

C. U. Wills has reconstructed, on the basis of the scant evidence left after the Maratha invasion, a Haihaya administrative political organization that also accounts for the concept of thirty-six forts (1919:197–262). He speculates that the system was five-tiered, beginning with the smallest unit of the village. Twelve villages formed what was called a barḥon, derived from the Chhattisgarhi word for “twelve.” Seven barḥon formed a caurāsī or garḥ (caurāsī means “eighty-four”; every garḥ or caurāsī consisted of eighty-four villages). The next tier was the northern and southern branches of the Ratanpur dynasty, each ruling over eighteen garḥ. Finally, the entire kingdom would have consisted of thirty-six forts under the dominion of the senior ruling family at Ratanpur. Wills contends that while the precise numbers were probably more theoretical than actual, these ...