![]()

Part One

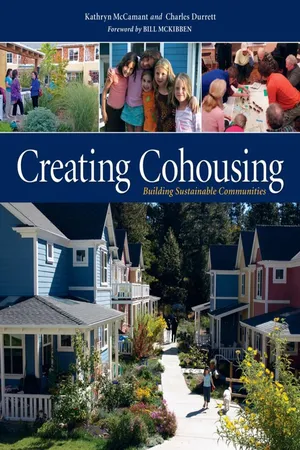

Introducing Cohousing

As we observed in our first edition of this book, traditional forms of housing do not address the needs of most Americans. As dramatic demographic and economic changes continue to shape our society, many of us feel the effects of these trends in our personal lives. Many people feel alone, isolated, and disconnected: they are mis-housed, ill-housed, or unhoused. Cohousing helps individuals and families to find and maintain the elements of traditional neighborhoods — family, community, a sense of belonging — that are so sorely missing in our society. Pioneered in Denmark, the cohousing concept reestablishes many of the advantages of traditional villages within the context of twenty-first century life.

Dinner outside at Cotati Cohousing.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Addressing Our Changing Lifestyles

After work, I pick up groceries while my husband picks up the kids from childcare. Once we get home, we cook dinner, clean up, and put the kids to bed. We don’t have time for each other, let alone anyone else. There’s got to be a better way.

— a working mother

Over two decades ago, as a young married couple, we began to think about where we were going to raise our children. What kind of setting would allow us to best combine our professional careers with child rearing? Already our lives were hectic. Often we would come home from work exhausted and hungry, only to find the refrigerator empty. Between working and housekeeping, where would we find time to spend with our kids? Relatives lived in distant cities, and even our friends lived across town. Just to get together for coffee we had to make arrangements two weeks in advance and when the time arrived, we usually didn’t really have the time, but did it anyway. Who knew when we’d be able to get together again next? Most young parents we knew seemed to spend most of their time shuttling their children to and from childcare and playmates’ homes, leaving little opportunity for anything else.

So many of us seemed to be living in places that did not accommodate our most basic needs. Even if we saw a house we could afford, we didn’t really want to buy it. We dreamed of a better solution — an affordable neighborhood where children would have playmates and we would have friends nearby, a place with people of all ages, young and old, where neighbors knew and helped each other.

Professionally, we were amazed at the conservatism of most architects and housing professionals, and at the lack of consideration given to people’s changing needs. Single-family houses, apartments, and condominiums might change in price and occasionally in style, but otherwise they were designed to function much as they had for the last fifty years. In reaction, we had both already designed different types of housing. And we began to recognize that our own frustrations were indicative of a larger problem — a diverse population was attempting to fit itself into standardized housing types that were simply not appropriate for them.

The needs of a diverse population are far better served by cohousing than by traditional single-family homes.

The Loss of Community

For the last few decades, contemporary postindustrial societies such as the United States and Western Europe have been undergoing a multitude of changes that affect housing needs. The modern single-family detached home, which makes up 69 percent of American housing stock, was designed for a nuclear family consisting of a breadwinning father, a homemaking mother, and two to four children. Today, this household type is in the minority. In fact, even the family with two working parents is no longer predominant. The single-parent household is the fastest-growing type for the first time in American history, and for the first time ever, more than half of the women over eighteen in this country don’t live with a husband. Well over a quarter of the population lives alone, and this proportion is predicted to grow as the number of Americans aged 60 and over increases. Moreover, the trend toward suburban sprawl and single-family houses on large lots has fragmented our communities. Across America, too few houses are being built in and around the cores of towns and cities, and far too many are being developed several traffic jams away from downtown.

The ever-increasing mobility of the population and the breakdown of traditional community ties are placing more and more demands on individual households. These factors call for us to reexamine the way we house ourselves, the needs of individual households within the context of a community, and our aspirations for an increased quality of life. And to create a more sustainable way of life, communities need to build within existing neighborhoods to link land use and development with municipal services, public transportation, and infrastructure.

Since the first edition of this book, these factors have become more apparent, as has the dire need for solutions, both environmental and social. We continue to believe that cohousing provides a model to address these issues — and now, since the publication of our first book, more than 120 cohousing communities have been built in North America, with another 50 plus in the planning phase or under construction. Cohousing provides a serious template for living lighter on our planet and improving people’s quality of life in child- and senior-friendly neighborhoods.

A Danish Solution

In the mid 1980s, as we searched for more desirable living situations for ourselves, we kept thinking about the developments we had visited while studying architecture in Denmark several years earlier. After numerous futile efforts to obtain information in English about what the Danes were doing, we decided to return to Denmark and find out for ourselves. The first edition of this book, published in 1988, was about what we found. This third edition is based on our work with cohousing communities in North America and elsewhere over the past twenty years, and built on those initial Danish findings.

The first cohousing development was built in 1972 outside Copenhagen, Denmark, by 27 families who wanted a greater sense of community than that offered by suburban subdivisions or apartment complexes. Frustrated by the available housing options, these families created a new housing type that redefined the concept of neighborhood by combining the autonomy of private dwellings with the advantages of community living. It was a perfect fit for their contemporary lifestyle. Then, as now, their custom neighborhood was people- and elder-friendly. Its very design created opportunities for daily household cooperation in activities like meals and childcare. Along the way, their neighborhood placed a small footprint on the land and deemphasized the automobile — in fact divorced the automobile from the very paths that people walked, talked, and played on.

Then, like today, each household in a cohousing community has a private residence; each one is designed to be self-sufficient and has its own kitchen. But every household also shares extensive common facilities with the neighborhood, such as a large common house that includes a big kitchen and dining room, children’s playrooms, workshops, guest rooms, and laundry facilities. The common facilities, and particularly common dinners, are important aspects of community life for both social and practical reasons.

By 2010, more than 700 of these communities have been built in Denmark, with many more planned — an astonishing number considering that Denmark has a total population of five million. They range in size from 6 to 34 households, with the majority between 15 and 33 residences. In Danish, these communities are called bofællesskaber (directly translated as “living communities”), for which we have coined the English term “cohousing.” The cohousing trend continues throughout Europe, the United States, and Canada, with new projects being planned and built in ever-increasing numbers. In Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, Canada, and now New Zealand and Australia, more and more people are finding that cohousing addresses their needs better than “traditional” housing choices. Likewise, cohousing communities are evolving to fit our ever-changing and ever-broadening definitions of a household to accommodate single parents, single elders — even families of six.

Residents share a pleasant dinner together on the common terrace.

Imagine . . .

It’s five o’clock in the evening, and Michelle is glad the workday is over. As she pulls into her driveway, she begins to unwind at last. Some neighborhood kids dart through the trees, playing a mysterious game at the edge of the gravel parking lot. Her daughter yells, “Hi, mom!” as she runs by with three other children.

Instead of frantically trying to put together a nutritious dinner, Michelle can relax now, spend some time with her children, then eat with her family in the common house. Walking through the common house on her way home, she stops to chat with the evening’s cooks, two of her neighbors, who are busy in the spacious kitchen preparing dinner — baked turkey breast with mushroom sauce and mashed potatoes, with steamed carrots and broccoli on the side. Several children are setting up tables in the large dining area nearby. Outside on the patio, some neighbors share a pot of tea in the late afternoon sun. Michelle waves hello and continues down the lane to her own house, catching glimpses of the kitchens of the houses she passes. Here a child is seated, doing homework at the kitchen table; next door, John ritually reads his after-work newspaper.

After dropping off her things at home, Michelle walks through the birch trees behind the houses to the childcare center, where she picks up her four-year-old son, Peter. She will have some time to read to Peter a story before dinner, she thinks to herself.

Michelle and her husband, Eric, live with their two children in a housing development they helped design. Not that either of them is an architect or builder: Michelle works at the county administration office and Eric is an engineer. Six years ago they joined a group of families who were looking for a realistic housing alternative. At that time, they owned their own home, had a three-year-old daughter, and were contemplating having another child — partly so their daughter would have a playmate in their predominately adult neighborhood. One day they noticed a short announcement posted on a message board at their local grocery store:

Most housing options available today isolate the family and discourage a neighborhood atmosphere. Alternatives are needed. If you are interested in:

• ...