![]()

PART I

Attitudes

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Garden Farming

New and old at the same time, garden farming has historical antecedents and contemporary examples all over the world. At its simplest it is no more than the efforts of people to provide for their own needs from their immediate surroundings, work that connects us directly to our Neolithic ancestors. Dressed up in the patriotic colors of Victory Gardens during World War II, garden farming grew 40% of America’s produce.1 Small farms are still the pattern in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Poland, Slovenia and many other developed Asian and central European countries.

In the Soviet Union, where the state-run collective farms were notoriously inefficient and food shops were often empty or offered limited supplies, the Russian people learned to supplement their diet from produce grown at their dachas, small summer cottages just beyond the urban fringe. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, these peri-urban garden farms were a lifeline that prevented mass hunger. People simply planted extra rows of potatoes and cabbages, and when they couldn’t get fuel to drive out to the country, took the bus or rode a bike. Private allotments surrounding cottages today grow 50% of the country’s vegetables, fruits and dairy on 7% of the land.2

These and other examples throughout this Permaculture Handbook will show that much of garden farming is about meeting household needs — what in permaculture is called self-reliance — a term that I distinguish from the more commonly used phrase, self-sufficiency. Self-sufficiency implies not needing any supplies from outside. Many 19th and early 20th century farms in Europe and the US were self-sufficient, buying only salt, tea or yard goods and other luxuries. Self-reliance, on the other hand, is about taking responsibility for one’s own household needs as part of a resilient local economy. Trade and barter will be important components of a self-reliant economy. In the US, Amish communities produce a great deal of their own food, clothing, tools and household goods locally, but they are also involved in a great deal of trade. Where there is no local source for some items, they are purchased by mail order from other Amish producers or even “English” neighbors or commercial concerns.

Building Self-Reliance

Self-reliance is an aim of the permaculture design system. At the household and community level it increases security and independence, thus resilience, or the ability to absorb shocks and disturbances and to recover quickly from them. Self-reliance reduces dependence on distant sources and suppliers and thus reduces the energy intensity of food and other essentials, shrinking our ecological footprint. By meeting most of our own needs, we minimize the damage and dependency caused by global trade, more easily regulate our consumption and conserve resources. We also bolster our own capacity for survival and prosperity as well as our ability to aid others around us. Self-reliance is not about isolation, nor is it a dogma; rather it describes a rational hierarchy of independence and interdependence from which we can make ethical decisions about what we consume...and what we produce.

My own permaculture teacher, Lea Harrison, told a story that has remained with me about self-reliance. When visting the flat lowlands of Nepal in the 1980s to teach permaculture, she saw — in an area called the Terai — many small farms with neat fields of millet, mustard, wheat and lentils, but there were few trees. As her hosts showed her around one village, she spotted a woodland across the valley which seemed to be of a very different character from the farms surrounding it, so she asked if they could take a look. It turned out to be the home compound of Mrs. Rai, a woman who ran a school for neighborhood children. Welcomed as a foreign dignitary, Lea was shown the grounds, which featured edible and economic species of every type; the children were pursuing their studies out-of-doors, under the tree canopy. Lea asked her Nepali host how she had come to this place, and why it was so different from all the farms around it. Mrs. Rai laughed and replied, “Well, you see, if I needed it, I planted it. And this is what happened,” explaining that her method was to grow everything that she and her students would use for food, fiber and medicine. The result was a food forest of the sort that Lea had been teaching her own students how to plant and cultivate. As we have learned time and again, no one has a monopoly on good ideas.

We each begin our journey toward self-reliance with the most essential elements and those we can supply most easily, and we continue replacing things we consume with things we produce (or eliminating consumption of needless items altogether), until it ceases to be economically sensible or practical to do so. For example, our southern Indiana household is unlikely anytime soon to grow tea or lemons, or to forge our own wrenches or strike our own nails. We haven’t turned off the water from the public system, but we use very little of it and should the need arise, we could supply our own for many months (or indefinitely) from roofwater caught and stored in tanks. We continue to shop in local markets, but we have food put by and we grow a lot of our own. Each year we increase the amount we grow and the amount we store, as well as the amount and variety of things we sell or trade. We are well started on the path to self-reliance, and I hope this book will encourage and empower you to set out on that path — and to make great strides along it.

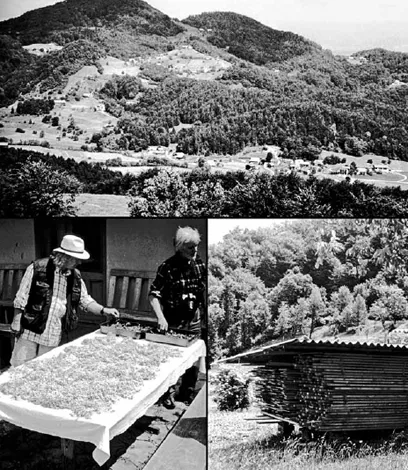

Self-reliance is an important aim for any society that hopes to endure the challenges of the coming decades. When I visited Slovenia in 2005, I saw a small nation of small communities. The capital Ljubljana has the population size of Madison, Wisconsin, or Windsor, Ontario, while the whole nation is about as big as New Hampshire. It has a temperate climate somewhat similar to that of eastern Pennsylvania, stretching between a narrow coastline on the Adriatic Sea and the Julian Alps. Throughout the countryside and in small towns, almost every house seemed to have a garden. Up the hills behind the houses were rows of grapevines, which my friends told me enabled most households to make their own wine.

Slovenia is a prosperous nation of two million people, a former Yugoslav republic that has become a member of the European Union. When we visited, the roads, rail lines and other infrastructure of the country were in good shape, and the markets and shops seemed to be full of a wide variety of goods. There were many cars in use, most of them fairly new or in good condition. The food we ate was of good quality and served to us in generous amounts. The people looked trim and healthy. There was little evidence of environmental contamination or pollution. By any standard, Slovenians enjoy a good quality of life, but the nation also demonstrates a high level of self-reliance at the household level.

Feeding the Cities

The idea that our towns and cities could feed themselves with a little help from the suburbs and the countryside nearby may strike most observers as preposterous, but, as this book attempts to show, the present state of agriculture and energy supply is so unstable that food security for town and country alike depends on our willingness to undertake self-reliance. There is no shortage of examples to inspire us. Hong Kong, one of the most densely settled territories on Earth, still managed during 2010 to grow a considerable amount of the poultry required by its inhabitants on land within the tiny enclave.3 Havana today, as a result of changes in post-Soviet Cuban agriculture, has over 35,000 urban gardens producing about half the fresh food consumed in that city of two million, plus a market selling local produce in each one of its 2,000 neighborhoods.4

Tenochtitlan, a pre-Columbian city of 200,000 on the site of modern Mexico City, was substantially fed from intensively cultivated water gardens nearby. Historically, food from these gardens traveled to market by canoe.5 Remnants of the gardens, called chinampas, persist today and are grown on raised beds in the shallow lakes.

Land is meticulously cared for in Slovenia, and domestic self-reliance is high: only single trees or small patches of forest are cut. Stacks of lumber can be seen curing throughout the countryside. Drying hay is roofed, and the flowers of elder and other perennials are harvested for home use and market. [Credit: Peter Bane]

Canals in the shallow lakes provide boat access to chinampas in Xochimilco, south of Mexico City. [Credit: Scott Horton]

New York at the turn of the 19th century was fed by a complex and productive garden agriculture on Long Island and from small farms up the Hudson Valley and in New Jersey. The term truck farming comes from the practice of trucking produce from farm to city markets, a matter of a few hours travel by horse-drawn wagon.6

Nor is the practice of self-reliance remote from us in either time or space. Today in North America, the fastest growing forms of agriculture are small peri-urban farms of less than 20 acres growing vegetables for market.7 Much of this movement is driven by a demand for local and organic food stemming from concerns about personal and ecosystem health. And quite a bit of it is off the official radar. North Americans are learning to be discerning food consumers, and farmers markets are burgeoning.8 This also means that many more people are choosing to start farming than at anytime since World War II.9

A New Sustenance

When the history of the 20th century is written two hundred years from now, one of the things I imagine writers will recognize as contributing the most to human evolution is the emergence of what is loosely termed organic agriculture. By that I do not mean the codification of certain practices under sanction of the US Department of Agriculture, but a broad movement that preceded and gave rise to that codification and which is likely to outlast that august but deeply corrupt agency. Rather, I point to forms of farming and gardening that generate soil fertility as well as crops for market and consumption — farming that can regenerate landscapes, ecosystems and even whole societies. Humans have practiced agriculture for 10,000 years without understanding why it works, and as a consequence most long-term agricultural practices and the civilizations built on them have collapsed from one or another failure to maintain ecological balance. Again and again, soils became exhausted, salted from irrigation, eroded because of plowing; the climate changed because too many trees had been cut or the population increased beyond the ability of farmers to provide food.

Faster than almost any other civilization, North Americans have destroyed their soils by plowing, poisoning and salting with fertilizer and irrigation. [Credit: erjkprunczyk via Flickr]

To understand the profound importance of regenerative agriculture, the kind of farming that builds natural capital, we need to see it not as a fringe or retrograde...