![]()

PART 1

ECONOMIC GROWTH AT THE CROSSROADS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

It Really Is the Economy, “Stupid!”

| | We should double the rate of growth, and we should double the size of the American economy! JACK KEMP | |

QUICKLY AND OMINOUSLY, bottles of drinking water have appeared on grocery shelves all over the world.1 Remember, it wasn’t that long ago when a bottle of water was a novelty for a grocery store. It wasn’t too surprising to see these bottles appear in big cities where the tap water tasted like chlorine for decades. But suddenly, bottled water is the norm, city and country alike.

Recently I was in Missoula, Montana, a place I hadn’t been in 25 years. Back then Missoula was a small town surrounded by wild country, known as the “gateway to the Rocky Mountains.” Now with well over a hundred thousand people, it is surrounded by middle-class McMansions: big sprawling houses with big sprawling lots, sprawling over the shrinking valleys and hills. Commercial development is concentrated in and around town, while agricultural activities cover much of the remaining landscape. Only the federally owned mountains in the distance remain undeveloped, though there are plenty of roads through them as well, and plenty of visitors doing plenty of things. And the grocery stores in Missoula have aisles full of drinking water, numerous brands and grades for quenching the thirst of everyone from carpenters to CEOs.

If people in Missoula, Montana, have to drink bottled water to feel safe—or simply to avoid a bad taste in their mouth—what does that say about the grandkids’ water supply over the vast areas of the United States that will be far more developed than Missoula?

When you buy bottled water, you have choices among spring water, distilled water and filtered water. The spring water, of course, tastes better (if it truly comes from a spring) and is more expensive. No one should take a spring for granted. It doesn’t just bubble up like upside-down manna from heaven. A spring is a natural seep where the water table, or aquifer, meets the surface of the land. Sometimes the water trickles down to a stream or brook, but most of the time it just seeps back into the ground a few feet away. In any case, a spring is a wonder to behold. Tall trees grow there and wild animals gather to drink. In dry country, you can spot a spring from miles away. All who have lived in the desert know how the sight of a distant spring brings a palpable sense of relief on a hot, dry day.

But springs can run dry, especially when you pump them. When I worked for the San Carlos Apache Tribe (which occupies a 1.8 million-acre reservation in Arizona) in the 1980s, business consultants convinced the tribe to sell bottled water from a large spring at the base of the Natanes Plateau. The plateau is the site of one of the most southwestern ponderosa pine forests in North America. Deer, turkeys, mountain lions, bears and the biggest elk in North America live in this forest. At its southern edge, the plateau ends abruptly at the thousand-foot Nantac Rim, which is inhabited by Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep. At the base are more deer, plus pronghorn antelope and javelina.

Arizona has a monsoon climate. It doesn’t rain a lot in Arizona, but when it does, it rains. When it rains on the Natanes Plateau, which is tilted to the north, most of the water goes charging into the Black River, and much of the rest evaporates quickly. What remains seeps into the soil, providing water for the forest and its wildlife. Some of it even seeps out the bottom of the Nantac Rim, providing water for the bighorn and javelina—and now, apparently, for the water-bottling company. I asked the consultants if they knew anything about the water capacity of the plateau, and they admitted they knew nothing of the sort. But of course the thought of this 200-square-mile plateau running dry left them incredulous.

The Natanes Plateau might not go dry for a long time, but that’s the point: we don’t know. All we know for sure is that water demands are increasing, and the water supply is not. And the plateau is a metaphor for society’s nonchalance toward water supplies. The grandkids will be even more incredulous than the water bottlers when the price for a bottle of spring water goes from $1 to $2, then $5 or more, as increasing demand ensures. And the grandkids of the San Carlos Apaches will be just as incredulous when the invisible hand of the market starts pumping the Natanes Plateau faster, when the ponderosa pines begin to thin, and when the world’s biggest elk retreat across the Black River, off the reservation, heading for the White Mountains.

Of course, once spring water is exorbitantly priced, people may simply resort to the substitute of distilled water (whereupon the price of that will rise) or even, heaven forbid, tap water! We can count these as two notches—from spring water to distilled water, from distilled water to tap water—out of the quality of life for the grandkids, and these are not small notches. If you’ve ever quenched your thirst with a good, cold drink of spring or well water, you know what I mean.

Oh yes, and there is the fact that much of the bottled water we buy is nothing more than tap water to begin with! But that’s another story.2

Missoula and San Carlos are among my first-hand observations related to the water supply of the United States, but most people who work with natural resources have their own water stories. Meanwhile moms and dads and even older kids, no matter how removed from the outdoors, have seen bottled water prices creeping upward. Anyone who’s still complacent about water should read Unquenchable: America’s Water Crisis and What To Do About It.3 Robert Glennon, one of America’s leading water supply experts, documents how aquifers—big ones—are running dry in the United States. Many or most regions in the world have water problems that are more dire than in the United States, most notably the Middle East, central Asia, most of Africa and much of Australia.4 The problem isn’t only water shortage; the human economy is polluting our water supplies world-wide even as they decline in quantity.5

If you aren’t ready to acknowledge that water shortage and water pollution are real and serious problems, you should probably stop reading now. Unless you want to consider your grandkids’ food.

When you go to a grocery store in the United States today, it’s hard to imagine that food could ever be a problem. If you’ve tried growing your own food, you realize that the bounty in the grocery store is truly breathtaking! The cereal aisle alone looks like a library. But when you look at the dozens of brands, it is also humbling to remember they are all made of just a few things: wheat, oats, corn and rice, for the most part. Then there is the meat section with its hundreds of cuts, grindings and delicacies. Almost all the beef, pork and poultry, however, was raised or fattened on wheat, oats, corn, milo and soybeans. The fish section is represented by a few dozen species, and the produce section by a few dozen fruits, vegetables and herbs. That basically does it. On we go through the grocery store, seeing this basic set of species presented in boxes, bags, bottles and cans (supplemented generously by refined sugars and a host of chemicals).

Except for some of the chemicals, this bounty is ultimately dependent on three things: soil, water and sunlight. Soil and water, at least, deserve our immediate attention.

We have already considered water, but now let us tie it to food production. The fact that we get so much of our drinking water shipped to us from remote places like the Nantac Rim is partly because so much groundwater closer to town is drawn for crop irrigation. Irrigation accounts for about 40 percent of all freshwater withdrawals in the United States.6 Our cities tend to be in plains and valleys near gently sloped agricultural areas, while the best bottled water comes from the steeper hills and mountains of the United States, Canada, Europe and Latin America. In California, where the vegetable crop alone is worth billions of dollars annually, agriculture accounts for 85 percent of water use. We are competing with our farmers, who keep most Americans and much of the world fed, for water! If this trend is not halted, at some point we will be faced with a choice between hunger and decent drinking water. Long before such a dire dilemma, of course, the city fountains will be shut off, our lawns will dry up and we won’t be taking many baths.

It makes you wonder: shouldn’t we cut down on some of the fountains, lawns and baths now? Some of them, at least, to buy some time for the grandkids? To buy some time while we figure out the bigger picture?

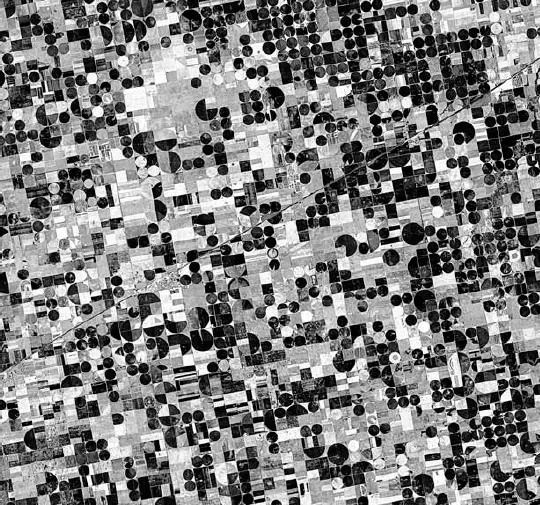

FIGURE 1.1. Satellite photography of pivot irrigation on roughly 720 square miles near Garden City, Kansas. Liquidation of the Oglala aquifer sets up one of many supply shocks awaiting future generations. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Meanwhile, the average citizen of the Western world seldom thinks about the soil, or “dirt.” It’s been a long time since an American president warned, “A nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.”7 Soil amounts to only a few inches or, on richer lands, a few feet of the Earth’s surface. When we farm, soil is exposed and runs off into rivers and eventually the oceans. Eroded soil is replaced over geological time by the decomposition of rock and organic materials, but the rate of replacement doesn’t nearly keep pace with the rate of erosion. Soil erosion in the United States is ten times faster than the natural replenishment rate; for China and India it’s 30 to 40 times faster.8 It’s not a declining problem, either, not even in the US where great pride is taken in the pace of agricultural innovation and technology. In the 1980s the soil lost on American farmland amounted to 1.7 billion tons annually.9 Two decades later the figure was 3 billion tons annually.10 It’s not surprising that crop yields have been reduced over vast areas of the United States. In many areas agricultural production would be non-existent—certainly not competitive in the market—were it not for massive applications of fertilizers.

The next logical thing to consider, then, is where the fertilizer comes from, and how it gets to the fields. It comes primarily from natural gas and phosphate rock, and it gets to the fields via train, truck and tractor. The cost of phosphate rock is increasing, even faster than the price of gasoline.11 Even for those economists who simplistically define scarcity as rising price (as opposed to an obviously diminishing resource) phosphate is becoming scarcer. Of course, for the rest of us, scarcity is a matter of common sense. A limited thing becomes scarcer as we use it up! For us, not only phosphates are becoming scarcer, but petroleum too, whether or not prices are proving it at any particular moment. Meanwhile the trains, trucks and tractors used to transport phosphates run on petroleum.

Not too long ago an economist absurdly remarked, “Worldwide, oil has been growing more plentiful, but for all we know it may some day become more scarce”.12 This telling observation was based on the fact that the price of oil had declined over the previous two decades. In other words, new oil discoveries of existing oil and the development of extractive technologies more than kept pace with demand during that period of time. But really, “growing more plentiful?” Most people know that oil is the product of organic material decay, but that doesn’t mean oil is constantly being produced, making it a renewable resource like timber or fish. Oil deposits represent organic material decomposed millions of years ago in rare events that produced “source rocks,” which then had to be buried between 7,500 and 15,000 feet below the Earth’s surface to generate oil.13 A phrase such as “growing more plentiful” is a huge red flag waving over the field of economics. It is hard to think of a good analogy for such a statement, but it is roughly akin to saying, “The food on my plate grows more plentiful, even as I eat! After all, each movement of the fork to my mouth costs me no more calories than the preceding movement. In fact, with the calories I’ve just converted, I’m finding it easier to move the fork, so there must be more food there, not less.”

FIGURE 1.2. Pivot irrigation in the Wadi As-Sirhan Basin of Saudi Arabia, February 21, 2012. Fields in active use appear darker, fallow fields are lighter. Most are approximately one kilometer in diameter. As in Kansas, the water is pumped from underground. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

The grandkids’ plight may or may not hinge upon an oil shortage. If the renowned petroleum geologist Kenneth Deffeyes is right, however, it may be you and I who deal with the shock of severe oil shortages. Deffeyes studied under Marion King Hubbert, who in 1956 predicted the peak of American oil production would occur in the early 1970s. Hubbert was subjected to widespread ridicule in academic and industry circles, but he was right. In fact, his prediction was a smidgen conservative, for by 1970 American production of crude oil started to fall. Three years later, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) capitalized on this development, shocking the world with 300–400 percent increases in crude oil prices and plunging the United States and Europe into the biggest recession since the Great Depression.

FIGURE 1.3. Tar sands mining operations north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada. Credit: George Wuerthner

Deffeyes grew up in the oil fields and spent his life in the oil business, progressing from a roughneck to a researcher of the highest scientific credentials. He built upon Hubbert’s model and extrapolated it to the world, reporting his findings in Hubbert’s Peak (2001). He predicted the peak in world oil production would occur bet...