![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Fertile Ground

TRANSPLANTING USED TO MAKE ME VERY NERVOUS when I first started farming. There’s something about gently holding tiny leek seedlings between my two fingers. They look more like a blade of grass with a clump of delicate roots on one end. My maternal instincts kick in. I feel the urge to protect the leeks from the cold of late April. Quick, get them tucked into some rich, loamy soil; then water to prevent those roots from drying out.

Come harvest time six months later, my relationship with those baby leeks evolves to a power struggle. I need a damn potato fork to dig out those buggers. The mature leeks’ roots are now so entrenched in the soil it takes serious effort to harvest them. I’m careful, however, to avoid damaging the roots. Leeks with an intact root system store in our root cellar readily for months.

Those leek roots quickly embraced their soil and established a strong hold and spread out to absorb nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and other nutrients.

According to Colorado State University Extension, 80 percent of plant disorders begin with root and soil problems. A plant becomes stable through strong roots, safely anchoring the plant and lessening the threat of soil erosion. Roots significantly affect a plant’s ability to adapt to different soil types as well as its ability to tolerate stress and change, which increasingly happens as a result of climate change. According to the Academies of Science, representing 80 countries, 95 percent of climate researchers actively publishing climate papers endorse the consensus position that climate change exists. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) cites that the Earth’s average temperature has risen by 1.4°F over the past century and is projected to rise another 2 degrees, to 11.5°F, over the next hundred years.

Roots represent our foundation, that grounding from which we grow. Our history plays a leading role in determining our future. Our roots shape our perspectives and outlook in life and our future farming endeavors. Roots also define our relationship and connection to our past. Before catapulting into careers in farming, let’s step back and understand from where we came. We’re part of a greater past, shared with our soil sisters who have been growing food for centuries. Unfortunately, much of this work has gone unrecognized or underappreciated in most of history. Taken for granted. Anyone traveling to some so-called developing countries may see this social inequality still vividly playing out today.

In this chapter, we pay homage to and learn from our shared history as women in agriculture. I’ll examine our personal history, reflecting on our life experiences to this point and considering how we can use them to fertilize our farming future.

“I have never felt more like a woman than the day I dug my hands into the soil for the first time. I’ll never forget the feeling of my hands after my first season of farming.”

— Natasha Bowens, author of The Color of Food

Natasha Bowens volunteering on an urban farm in Brooklyn during her hopping days.

Condensed history of women growing food

While female farmers appear to be the new fresh hipsters, step back and place today’s trendiness in historical perspective. Our boots have been on the ground growing food for a long, long time. Families, communities, and the world eat because of women. The paleo diet may be the modern rage, but women were the first food gathers back in those cave people days of yore.

Agriculture involving crop seeding and domestication of plants and animals started popping up on the human history radar around 10,000 years ago, and this role of household food management continued for women as food preservation and preparation techniques evolved from fermenting to baking. For those of you with kids in the house, someone in the past 24 hours probably has wandered through the kitchen inquiring, “What’s there to eat, Mom?” From the cave to the contemporary pantry, we’re the ones the world turns to when hunger hits.

While this role of food provider and preparer serves a vital role in society, female contribution in this category has historically gone unrecognized. If a tree falls in the woods and it isn’t posted on Facebook, did it really happen? Status updates can be misleading. How many seeds have we planted and peas have we shucked? While we know how many hamburgers McDonald’s sold last year — 75 per second, adding up to over 225 million — we have no idea how many home-made dinners have been served by women over that same period. In 1994, McDonald’s executives announced at the annual owner-operator convention that they would stop counting hamburgers served because the count had surpassed the 99 billion hamburger mark. Franchise operators changed their signs to the catchall “billions and billions served.” I’m tempted to hang a little glowing neon on my farm door too: “Woman-grown food served inside. Way beyond billions served, for 10,000 years and counting.”

“My grandmother’s laughter and her love of pie, the farm, and her family are the roots of my work. Living with fullness is honoring your ancestors and allowing their hopes to stay alive through you and your work.”

— Nancy Vail, co-founder and co-director of Pie Ranch, Pescadero, California

Invisible work and grass ceilings

Invisible and invincible. Two words close in spelling but worlds apart in meaning. They both narrate the story of the history of women farming and raising food. Until as recently as the late 20th century, women’s farm work and accomplishments never received much recognition when considered against the male-dominated paradigm. It’s like our tomatoes harvested or eggs sold never existed. The Census of Agriculture, conducted every five years by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), the statistical branch of the USDA, provides comprehensive agricultural data, which plays a big role in determining our nation’s agriculture and food policy. The census started counting women farmers only in 1978, two years after I dressed up as Laura Ingalls for Halloween. Despite this lack of acknowledgment, our boot heels stood firmly entrenched into the soil, fostering a foundation for a legacy that is blooming and — slowly — being recognized today.

The fact that, throughout most of history, women could not legally own property played a major role in gender inequity in agriculture. In 1887, one third of states still provided no protection for a married woman’s property. Once a woman personally sold anything grown on the farm, even if she raised it 100 percent herself, it legally transferred to her husband. By the 1900s, nearly every state had laws in place allowing a married woman to own property and sue in court, but practices and customs prevented their widespread adoption and situations were always even more challenging for women of color.

“Well into the twentieth century, farm assets were still in the husband’s name,” shares Dr. Jenny Barker-Devine, associate professor of history at Illinois College and author of On Behalf of the Family Farm: Iowa Farm Women’s Activism since 1945. “The IRS classified the wife as a dependent, which made it extremely difficult for a woman to claim property and farm assets of her husband in the event of his death or a divorce.” Property rights most likely went to the next of kin, such as brother.

“We refer to nature as ‘Mother Nature,’ and to Earth as ‘Mother Earth.’ As a woman, awareness of our innate wisdom and connection grounds me, gives me confidence to push past limiting beliefs, and helps me blossom in my work. I believe it is time for women to reconnect and raise the energy and consciousness of our planet. Each of us, in our own individual ways, will help heal our Earth.”

— Nirav Peterson, founder of Mother Earth Solutions, co-founder of Hendrikus Organics, Issaquah, Washington

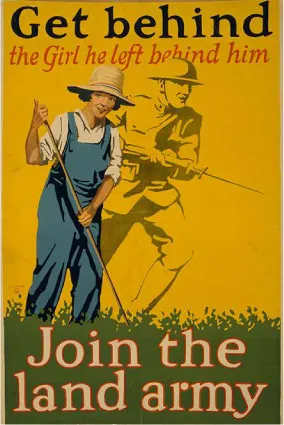

“Understanding our history makes us stronger and able to plan for a better future,” explains Dr. Rose Hayden-Smith of the University of California, a leading authority in the history of women growing food. She is the author of Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. “Women have long played an integral role in raising food, from home gardens to the farm fields, yet those contributions have gone largely unrecognized and thereby undervalued.”

One such example is the role women played in food security during World War I. Blending patriotism with planting parsnips, the Women’s Land Army of America (WLAA) officially organized in 1917 and ultimately recruited nearly 20,000 largely middle-class urban and suburban women during WWI to enter the US agricultural sector and work as wage laborers at farms, dairies, and canneries, often in rural areas where American farmers urgently needed help while the male labor force fought on the front lines.

“The WLAA wasn’t all about patriotism. Many of the women involved saw this as an opportunity to earn a wage and advance the idea that women were fully capable of such work,” adds Hayden-Smith. Inspired by similar programs started a few years earlier in the United Kingdom and Canada, the WLAA brought women of differing economic and geographic backgrounds together to till the soil, bridging urban and rural experiences as well as class differences, and challenging contemporary stereotypes relating to women’s role and work.

“Thousands of women, including wealthy socialites and debutantes, took an enormous chance by stepping out of their traditional roles to join a home front mobilization effort. By becoming farmers, these women challenged society’s understanding of the kind of work that women were capable of,” continues Hayden-Smith. “Before we earned the right to vote in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment, we served our nation with our hands in the soil. The WLAA played an important role as part of this larger argument that women deserve full citizenship….”

“The message reversed after WWI when the men returned from war and took their farm jobs back,” says Hayden-Smith on why the WLAA didn’t continue during peacetime. “When the war ended, it was seen as an act of patriotism to give your job to a returning soldier.”

An underlying cause of this lack of representation of women in agriculture stems from women’s traditional role as wives. “Historically, a woman was connected to the land through the men in her life, whether it was her father, brother or, most likely, a husband in marriage,” adds Barker-Devine. “Women primarily iden...