![]()

I BEGAN MY 20-YEAR FORAY into the world of sustainable building as an idealistic and completely inexperienced amateur wanna-be homeowner — just a guy with big dreams, very limited means, and almost no idea of the complexity of the task I was attempting. Armed with one book (and no internet!) and great intentions and expectations, I plunged my family into a long-term adventure that changed all of our lives.

Though I wouldn’t trade my personal experience for any other, I will gladly attest to the flaws of my naive approach. In fact, so flawed was this way of doing things that for two decades I have centered my life around helping others find their way to their own dream green home without hitting as many of the snags and making as many mistakes as I did.

There are many times in our lives when we make rash decisions and don’t adequately prepare ourselves for a task. Most of the time, making a less-than-ideal choice isn’t that big a deal — a poor choice can get chalked up to “live and learn.” However, poor choices in home building can be extremely costly, and the results can have real and serious implications for decades to come. When your life’s savings and a vast amount of your time and effort are on the line (not to mention large quantities of the planet’s current and future resources), “oops” is not a word you want to hear! The world of homebuilding is not a place you want to wander in blind and be directed by hard knocks.

Sadly, I have watched an awful lot of people plunge into homebuilding only to make the same, predictable, costly and demoralizing mistakes that I did. I have seen many homes built well-over budget that also underperformed — never meeting the high expectations their owners had at the outset.

As much as I’d like to be able to offer a “silver bullet solution” that would guarantee quick-and-easy results, I’m afraid there is no fast track, sure-fire method to figuring out how to build yourself the best possible home. I have spent two decades deepening my knowledge of how to make a really good building, and I still have lots to learn. It’s a vast subject, and the determining factors are many: climate and site, local regulations, available resources and skills, and, of course, budgets, which vary widely, as do individual considerations of comfort and aesthetics. There is no one “perfect” way to balance all of these factors; each project requires unique adaptations.

The uniqueness and “specificness” of homes — which I believe is essential for making a house into a home — has been largely abandoned for a one-size-fits-all simplicity that suits the needs of the large-scale construction industry but has done a large disservice to humans, the built environment, and the planet. This is not to say that good homes cannot be simple, but rather that the pathways to arrive at a good home design are as varied and many as the number of people who need and want homes.

Challenges and Rewards

We are at the beginning of a major period of disruption in the building industry. Pressures from many directions are forcing important changes in the practice of home design and construction, including more stringent energy efficiency codes, concerns about occupant health, and the imperative to reduce carbon footprints and change to clean energy sources — all of which are having dramatic effects on how we build. The cost of property, materials, and labor has been on a steep incline for over a decade. It is a constant challenge to find the best ways to meet a reasonable budget target and achieve a high level of performance, and if the intention is to also use the healthiest possible materials, the challenge is amplified. Add in a dash of aesthetics and a fair share of bureaucratic red tape and regulatory hurdles, and you have a serious challenge on your hands.

The effort required to prepare yourself for this particular adventure is great, and the decision to move forward must begin with acknowledging that you are about to engage in a process that will be all-consuming for at least a couple of years. If this idea doesn’t appeal to you, don’t go down this path. Give this decision the weight it deserves. Put it on par with decisions of the magnitude of changing your career, going back to school, or moving to a new city or country.

But before I discourage you from even considering setting foot on this path, I should mention the incomparable satisfaction that comes from settling down for an evening in a home that you have designed and built for yourself, your family, and your friends. In a world where many of the archetypal “coming of age” moments are absent or watered down, weathering your first literal storm sheltered in your own home is a great and deep satisfaction. And if you can manage to get through that storm with the lightest possible footprint on the planet and the healthiest possible environment surrounding you, the satisfaction goes beyond just a personal achievement and becomes something that will be an integral part of your life and a legacy that will live long beyond your time on this planet.

It’s my hope that you can make your project a forward-looking legacy, one that provides you and your family with all that they need while also achieving the goal of sustainable development — nicely defined by the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”1

![]()

![]()

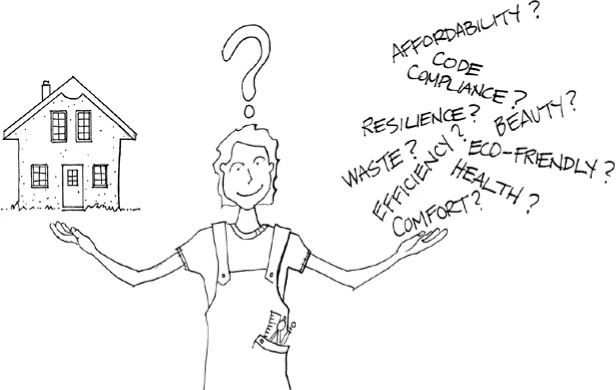

MOST BOOKS ABOUT HOME DESIGN jump right into the process of actually putting a house design to paper (or, in the modern context, to a software program). We’re not going to get to that stage for a while. Of course, this is an essential part of designing a sustainable home, and it will be covered here in reasonable detail, but designing a sustainable home requires much more than putting lines onto a drafting board in the right order. It needs to start not with drawings, but with goal setting.

The fact that you are reading a book about sustainable home design indicates that you have an interest in setting a goal for your project that in some way addresses key issues of personal and/or societal sustainability. However, each of us probably means something different when we use such a term — and the words we use may themselves be different. Terms such as sustainable, healthy, eco-friendly, natural, green, environmentally-sensitive, and net zero are often used — sometimes interchangeably — to describe the kind of better home an owner desires.

Measurable outcomes as the basis of decision-making

It just won’t work to begin your home design based on a couple of turns of phrase and a vague notion of what they mean to you. This book is not a treatise on semantics, so we’re not going to try to define any terminology for you. Instead, we are going to focus on defining the actual goals that you are setting out to achieve when you use such terminology. Rather than relying on simple taglines, we’re going to focus on well-defined goals and measurable outcomes. If you can knowledgeably set the targets you’d like your project to hit, your chances of succeeding are vastly increased.

Understanding Your Objectives

The unique intention of this book is to help you understand, define, and refine your objectives so that you can make informed choices — from initial siting considerations, through personnel decisions, and down to the level of individual material and system selections. It is critically important to acknowledge that your goals can be undermined by poorly informed choices at any stage of your project. If you fail to set appropriate goals at the “meta” level, then the chances of your project succeeding are greatly reduced, and if you do not ensure that each individual choice you make — throughout the process — adheres to the goals you’ve set, the results will likewise be undermined.

A good building means different things to different people.

For example, it is the goal of many homeowners to create an energy-efficient home. At the “meta” level, this would involve setting a hard target — for example, meeting current Energy Star or Passive House standards. With this kind of clearly definable goal, it becomes possible to make informed and appropriate design, material, system, and personnel decisions. In this case, the clear goal of meeting a particular efficiency standard would narrow down the selection of design professionals to those trained to meet that standard, and it would help with the selection of insulation materials, doors and windows, and mechanical systems appropriate to meeting the standard. Any choice that would subvert the larger goal is easily discarded in favor of one that harmonizes with the overall intention of the project.

Much of this book is dedicated to helping you set these overarching goals because clarity on the relatively small list of guiding issues greatly simplifies the very large list of decisions that need to be made during a design/build project.

Learning to think “sustainably”

The mechanics of decision-making are quite straightforward: we weigh up all the pros and cons of competing choices, and we choose the option that has more pros than cons.

What makes it onto the scales during decision-making, and why?

The process is no different when you are aiming to make a sustainable home, but the way in which we draw up the list of pros and cons includes some factors that are very often overlooked. We have to check some deeply ingrained biases if we are going to make the best choices.

New ideas versus established solutions

When considering new solutions, our approach tends to be one of two extremes. There are those of us who are inclined to accept the promises of a new solution without applying much rigor toward finding out if the promises are true, and there are those of us who tend to dismiss the promises of new solutions, also without the application of much rigor in our examination.

One of the first questions I am often asked when discussing new approaches to building is: “Does [insert name of material or system] really work?” This is an entirely appropriate and important question to ask, and it’s not unusual that we should have this question when faced with something new. The “new solution paradox” is that we typically only ask it of new solutions, and completely fail to question existing, accepted solutions. There is an assumption that the ideas, materials, and systems we use commonly have somehow been “proven” to work, that they have been rationally measured and found to be the best means to achieve a particular end. In the realm of building materials and systems, however, development, testing, and establishment of industry standards have been far from rational and well-proven processes. As most readers of this book are already aware, most of our accepted solutions have not been developed with any coherent ecological principles or human health ideals in mind....