![]()

Chapter One:

Beyond Zero: The Time Value of Carbon

by Erin McDade

A Global Carbon Limit

IN DECEMBER OF 2015, the world came together in Paris for the United Nations’ 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21), and signed the historic Paris Climate Agreement. This agreement commits almost 200 countries to helping limit global temperature increase to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.”

These temperature increase limits are in response to the international scientific community’s widely accepted two-degree Celsius tipping point. Global temperatures have been increasing steadily since the industrial revolution, but the scientific community believes that if we can peak our global increase and begin to cool the planet before we gain two degrees, the effects of climate change will be reversible. In other words, if we meet this target we can return the planet to pre-industrial conditions. However, scientists believe that if we pass that two-degree threshold, the effects of climate change will begin to cascade, spin out of control, and become irreversible.

Buildings Are the Problem; Buildings Are the Solution

In addition to the historic signing, COP21 made history by hosting its first ever Buildings Day in recognition of the crucial role that the building sector must play in reducing global CO2e emissions. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that constructing and operating buildings accounts for nearly half of all US energy consumption and fossil fuel emissions. Globally, cities consume nearly 75 percent of the world’s energy, mostly to build and operate buildings, and cities are responsible for a similar percentage of global emissions. The building sector is a significant part of the climate change problem, but this also means that if we can eliminate carbon emissions from the built environment, we can significantly reduce overall emissions, ameliorating and potentially even solving the climate change crisis.

Zero by 2050

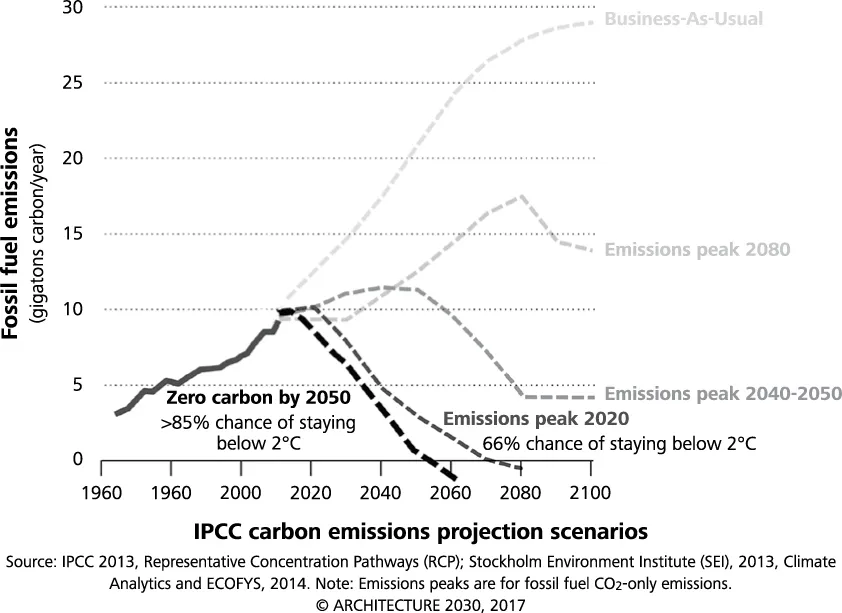

According to the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the organization that hosts the annual Conference of the Parties, global temperatures have already increased by 0.85 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times, meaning that we’re nearly halfway to our maximum temperature increase threshold. In order to predict future temperature increases as they relate to fossil fuel emissions, the IPCC periodically publishes projections based on a number of global patterns, ranging from business as usual to aggressive emissions reductions. In 2013, prior to the Paris Climate Agreement, the IPCC published four projection scenarios. The business-as-usual scenario, in which our consumption of fossil fuels continues to grow exponentially, projected that we would pass the two-degree tipping point around 2040. Even the more aggressive reduction scenarios, in which global emissions peak between 2050 and 2080 and then begin to diminish, showed us passing a two-degree increase near 2050. While an extra decade below two degrees would certainly be an improvement, following these projections would simply be delaying the inevitable — climate change would still spin out of control and become irreversible. The fourth and most aggressive scenario published, in which global emissions peak and begin diminishing in 2020, gave us our best chance of staying below the two-degree Celsius threshold, but unfortunately still predicted a large chance of surpassing that tipping point.

In response to the Paris Climate Agreement’s aggressive target of a 1.5-degree maximum increase, the IPCC published an additional emissions scenario that gives us an 85 percent chance of staying below a two-degree increase. However, this scenario requires global carbon emissions to peak immediately, and for us to fully phase out our use of fossil fuels, in every sector, by mid-century. This means that in order to meet the targets set forth by the Paris Climate Agreement, the global building sector must be carbon free by the year 2050.

The Zero Net Carbon Gold Standard

Since the beginning of the green building movement in the 1970s, the design community has focused mainly on increasing the efficiency of operating our buildings — reducing the energy consumed (and carbon emitted) in keeping everyone warm (or cool), keeping the lights on, etc. Both technology and design have improved drastically in the last 50 years, and now Zero Net Carbon (ZNC) is the gold standard for sustainable construction. A ZNC building is a highly efficient structure that produces renewable energy onsite (typically using photovoltaics), or procures as much carbon-free energy as it needs to operate. ZNC buildings are being constructed globally in almost all climate zones, space types, and sizes, proving the viability of this standard, and their reduced carbon emissions are being documented.

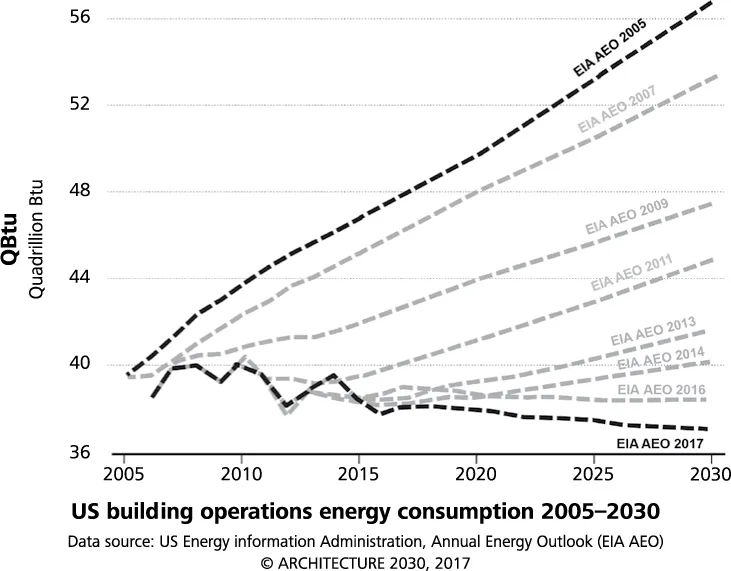

Each year the US Energy Information Administration publishes the Annual Energy Outlook, predicting future US energy demand based on current consumption trends. In 2005, before Architecture 2030 launched the 2030 Challenge and catalyzed the US and global building communities to begin targeting zero operational emissions by 2030, the EIA’s projections predicted exponential growth in building operational energy consumption. Following the launch of the 2030 Challenge, each subsequent year’s projections showed a decrease in energy consumption, and projections flatlined in 2016. The EIA’s 2017 projections predict that US building operations will consume less energy in 2030 than in 2005, despite consistent and significant growth in the building sector. With this downward trend, and the increasingly frequent construction of ZNC buildings, the world seems on track for meeting the widely adopted commitment to zero operational carbon emissions by the year 2030.

Embodied Carbon:

Getting to Real Zero

However, the emissions resulting from operating our buildings only represent one side of the coin. In fact, even before a building is occupied and any energy has been used for operation, the building has already contributed to climate change — usually in a significant way. These mostly unnoticed effects are the result of the construction process itself, and include emissions resulting from manufacturing building products and materials, transporting them to project sites, and construction. We refer to this as embodied energy (energy consumed pre-building operation) or embodied carbon (carbon emitted pre-building operation). To date, even within the green building community, these emissions are usually ignored in the conversation about the building sector and climate disruption.

On day one of a building’s life, one hundred percent of its energy/carbon profile is made up of embodied energy/carbon. Embodied carbon emissions end upon the completion of construction, while operational carbon is emitted every day for a building’s entire life. (Well, not quite. All buildings get maintained, painted, reroofed, remodeled, added to, repaired, and so on, causing embodied carbon to continue to climb slightly in short bursts. But for most buildings this effect is minor by comparison, so for this discussion we treat embodied carbon as just that from the original construction.) Over the life span of a typical building, the cumulative operational emissions almost always eclipse the initial embodied ones, and by the end of the building’s life, embodied energy accounts for only a fifth or less of the total consumed by the building. Even if that same building is constructed to operate twice as efficiently, cumulative operational emissions are still greater than initial embodied ones. (See Figure 1.3.)

Since embodied energy accounts for an average of 20 percent of a building’s total energy consumption over its life, it is understandable that the building sector’s historic focus has been on operational (instead of embodied) energy and carbon. However, with the signing of the Paris Climate Agreement committing the world to a carbon-free built environment by 2050, we clearly can no longer ignore embodied carbon. In fact, new research indicates that to date we have significantly underestimated the significance and time sensitivity of embodied carbon in overall building sector emissions.

Emissions Now Hurt More than Emissions Later: The Relative Importance of Embodied Carbon

Over a typical building’s 80–100-year life span, operational emissions dwarf embodied emissions. But if our deadline for eliminating building sector emissions is three decades or less, the timeline is much shorter and the relative importance of embodied carbon changes. Assuming a building is constructed today and operates 50 percent more efficiently than a typical building, by 2050 only 45 percent of the energy consumed by that building will have been used for operations, meaning that 55 percent of that building’s total energy consumption is embodied energy. And the closer to 2050 the building is constructed, the more embodied carbon emissions eclipse operational carbon emissions. Furthermore, as we target ZNC for all new construction and buildings are designed to meet increasingly rigorous performance standards, the amount of operational carbon emitted decreases and is eliminated, meaning all of a building’s carbon emissions are the result of embodied carbon. (See Figures 1.4 and 1.5.)

Embodied Carbon in the Future

Between 2015 and 2050, more than two trillion square feet of new construction and major renovations will take place worldwide,1 the equivalent of building an entire New York City (all five boroughs) every 35 days, for 35 years straight! If the built environment is to be carbon free by 2050 and meet Paris Climate Agreement targets, how we in the design community design and construct this two trillion square feet, and how we value and evaluate its embodied carbon, is crucial.

Even conservatively assuming that all of this new construction operates twice as efficiently as typical construction, between now and 2050, 80–90 percent of its energy profile will be made up of embodied, not operational, energy. The carbon math is similar though not identical due to variations in grid energy emissions.

This isn’t to say that operational perfor...