- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Readings in Innovation

About this book

Each year from 1978 through 1987 the Center for Creative Leadership hosted an event called Creativity Week, during which a select group of researchers and practitioners would get together for a high-energy exchange of ideas on organizational creativity. Discussions explored such themes as individual innovation, creativity and teamwork, structuring the organization for innovation, and the relation of innovation to culture and technology. This book, which offers papers based on many of the best Creativity Week presentations, is thus a record of recent thinking, both practical and theoretical, on how organizational effectiveness can be improved.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Readings in Innovation by Stanley S. Gryskiewicz, David A. Hills in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Leadership. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Research

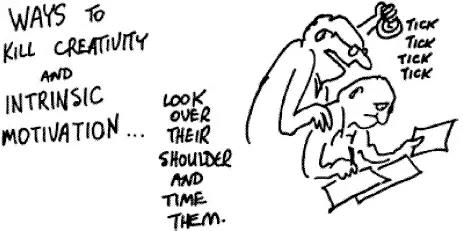

Social Environments That Kill Creativity

Toward the end of the last century, a boy was born to a Jewish engineer and his wife in a small German town on the Danube River. Slow and shy, this boy did so poorly in school that, when his father asked the headmaster what profession his son should adopt, the answer was simply, “It doesn’t matter. He’ll never make a success of anything.” He did make a success of something, though, but he almost seems to have done it in spite of his schooling.

As a youth, he attended a militaristic school in Munich that stressed discipline and memorization. Although he would never become famous for his views on education, his autobiography eloquently recalls the disdain he felt for such strictly controlled learning environments:

It is nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate little plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wreck and ruin without fail. It is a very grave mistake to think that the enjoyment of seeing and searching can be promoted by means of coercion and a sense of duty.

But coercion and a sense of duty were commonplace in those early school years. He later recalled the devastating effect that this external control had on his motivation. In particular, he hated having to cram for his science exams: “This coercion had such a deterring effect upon me that, after I had passed the final examination, I found the consideration of any scientific problems distasteful to me for an entire year.”

The young man’s name was Albert Einstein. If Einstein, who loved science even as a child, could be so adversely affected by a restrictive social environment, what impact does social constraint have on the creativity of less talented people?

For the last several years, I have tried to answer that question by studying the impact of various social and environmental factors on the creativity of both outstanding and ordinary individuals (see Amabile, 1983). This approach can be viewed as a necessary counterpart to the personality research that most creativity researchers have been conducting. While they focus on the personality traits that distinguish highly creative people from everyone else, I focus on the social conditions that can positively or negatively influence anyone’s creativity.

The Meaning of Creativity

Most definitions of creativity stress the importance of both novelty and appropriateness: A product or idea must be novel (different from what has come before), but it must also be appropriate to the problem (correct or useful or valuable in some sense). Obviously, the precise meaning of “appropriateness” changes from one work domain to another. If we are talking about mathematical creativity, an idea or an answer must be verifiably correct. If we are talking about artistic creativity, it makes more sense to think in terms of the appropriateness of the medium to the theme or in terms of aesthetic appeal. But whatever the domain, an idea cannot be merely novel to be considered creative; we have to distinguish between the creative and the purely bizarre.

I think it is important to include a third element in the definition of creativity: the nature of the task. Some tasks or problems are completely straightforward; the path to the solution is clear and can be performed almost by rote. These tasks are called algorithmic. For example, there is only one correct solution for an arithmetic problem such as this: 52 + 17 − 21. And there is only one way to bake a box cake according to the recipe—follow the steps outlined on the box. There is no room for creativity in the performance of these algorithmic tasks.

Other tasks are open-ended, such that the path to the solution is not completely clear and straightforward. These tasks are heuristic; some search is required. Heuristic statements of the above problems would be, “Find 3 numbers that can be added and subtracted to produce the sum 48” and, “Make a cake, choosing your own combination of ingredients.” This open-endedness is what characterizes creativity tasks, such as the discovery of a new mathematical system or the invention of a new kind of cake recipe.

The definition of creativity that I have used includes all three of these elements: A product or response is creative if it is a novel and appropriate solution to the task, and if the task was presented heuristically.

Social Influences on Performance

Kenneth McGraw has suggested that algorithmic tasks and heuristic tasks are affected differently by social factors. In particular, he discusses the effects of expected reward. McGraw (1978) has shown that the expectation of reward can enhance performance on algorithmic tasks but can undermine performance on heuristic tasks. For example, people usually do better on simple multiplication problems if they are working for reward. They usually perform more poorly, however, if they are expecting a reward for solving problems that require insight.

Here is an example: Sam Glucksberg (1962) presented subjects with a deceptively simple problem. They were given a candle, a box of thumbtacks, and a book of matches and were told to use only these materials in mounting the candle on a vertical screen. The problem could only be solved by emptying the tacks out of the box and using it as a platform which could be tacked to the screen. Clearly, this problem is a heuristic one; the path to the solution is not at all obvious at the start. Subjects who were told that they could earn money for finding the solution quickly took much longer to solve the problem than subjects who worked without any mention of reward.

Social constraints are any factors that control, or could be seen as controlling, a person’s performance. Things people normally view negatively, such as deadlines, surveillance and constrained choice, are considered social constraints. However, things that are viewed quite positively, such as working for a promised reward or expecting a favorable evaluation, may affect performance similarly. I believe that all social constraints can have the same effects as rewards, the same facilitative effects on algorithmic tasks and the same inhibitory effects on heuristic tasks.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

These ideas on constraint and performance come out of social psychological theories of intrinsic motivation. Mark Lepper, Edward Deci, and others have proposed that social constraints (or extrinsic constraints) can undermine intrinsic motivation, the motivation to do something for its own sake. They suggest that if people start out with a great deal of intrinsic interest in their work, and then someone places them under an extrinsic constraint while they are working, their intrinsic interest will be undermined (see Deci, 1975).

Lepper and his colleagues (1973) demonstrated this effect in a simple study with children. They chose children who had initially shown a high level of interest in playing with magic markers that had been placed in their nursery-school classroom. Individually, each of these children was asked to draw some pictures with the markers. The experimenter promised some of them an attractive reward if they consented to draw the pictures; he did not mention reward to the other children. Later, when they were back in their classroom, those children who had contracted for reward spent much less time playing with the magic markers than the other children did. It’s as if, during the experiment, the rewarded children had asked themselves, “Why am I doing this?” Since the reward was so obvious an explanation, the reward became, to them, their reason for drawing the pictures. As a result, they no longer saw themselves as interested in the activity for its own sake. And, back in their classroom, with no reward possible, they actually showed little interest. This undermining of intrinsic interest with extrinsic constraint has been shown in a number of other studies with both children and adults.

The implications of these findings are rather startling. Parents, teachers, and business managers generally assume that a little reward is a good thing and that a lot of reward is more of a good thing. How can it hurt to present children and adults with incentives for their work? This evidence suggests that it can hurt. Although rewards (and other constraints) can certainly motivate our performance in the short run, in the long run they may destroy our interest in our work.

After reading Einstein’s (1949) autobiography, I began to wonder if, perhaps, extrinsic constraints could have negative effects on performance in the short run, too. It seemed that, in addition to decreasing subsequent interest in a task, such constraints might make it more difficult for people to approach the task creatively.

A heuristic task—a task requiring creativity—is like a maze that you must wander through. There may be more than one way of getting out, and some exits are more satisfactory than others. There are no clear markers showing you the path, so a great deal of searching is required. If you are intrinsically motivated, you are in the maze because you want to be there. You will enjoy nosing around, trying out different pathways, thinking things through before blindly plunging ahead. You’re not really concentrating on anything else but how much you enjoy the challenge and the intrigue. And that approach will most likely lead you to creative solutions.

If you are extrinsically motivated, however, you see yourself as having been put in the maze by somebody else. You have to attain the external goal; you have to earn the reward, or win the competition, or get the promotion, or please those who are watching you. You are so single-minded about the goal that you don’t take the time to think much about the maze itself. Since you’re only interested in getting out as quickly as possible (reaching the goal as easily as possible), you may rush into a lot of dead ends without much thought. Or you may take only the most obvious, well-traveled route. Either way, you are unlikely to be creative.

If the task is algorithmic, of course, extrinsic motivation is no problem. An algorithmic task is like a straight hallway, rather than a maze. There’s no question about the right way to go—straight ahead. You can forge ahead quickly and blindly, and extrinsic motivators might just make you run faster.

This, then, is my intrinsic motivation hypothesis of creativity: Intrinsic motivation will be conducive to creativity, but extrinsic motivation will be detrimental. On noncreative (algorithmic) tasks, performance should not suffer under extrinsic motivation. But performance on creative (heuristic) tasks should be undermined.

A Model of Creativity

I do not mean to suggest that intrinsic motivation is all we need to be creative. Certainly, we cannot just leave children alone, in their natural state, and watch their creativity blossom. And we cannot expect to just leave adults to their own devices and watch them produce creative work on any task they undertake. In my theory of creativity, I outline three components that are necessary for creative work in any domain: domain-relevant skills, creativity-relevant skills, and task motivation.

Domain-relevant skills include knowledge about the domain in question (for example, knowledge about chemistry), technical skills required for work within the domain (such as laboratory skills), and special domain-relevant talent (such as a talent for visualizing molecules and their interaction). Domain-relevant skills depend on cognitive abilities, perceptual and motor skills, and formal and informal education. As another example, domain-relevant skills for musical creativity in our culture might include a familiarity with Western music forms and instruments, the ability to play an instrument and to transfer ideas into musical notation, and a special talent for hearing in imagination several instruments playing together. Domain-relevant skills can influence creativity on any task within the domain of endeavor—any research in chemistry, for example, or any musical composition.

Creativity-relevant skills include a cognitive style marked by an ability to break mental habits and an appreciation of complexity. Also included is a work style characterized by an ability to concentrate effort for long periods of time, a sense about when to leave a stubborn problem for a while, a generally high energy level, and an implicit or explicit knowledge of creativity heuristics. The last simply involves rules of thumb for generating ideas—for example, “Try something counter-intuitive.” Creativity-relevant skills can be influenced by training, by experience in generating ideas, and by personality characteristics. Creativity-relevant skills operate at the most general level; they can influence performance in any domain.

Task motivation can be very specific to particular tasks within domains, and may even vary over time for a particular task. As I have suggested, an intrinsic task motivation (doing the task for its own sake) should be more conducive to creativity than an extrinsic task motivation (doing the task as a means to some extrinsic goal). Overall task motivation will depend on both the individual’s initial attitude toward the task (we all have our somewhat idiosyncratic preferences for activities) and the presence or absence of salient constraints in the social environment. If such constraints are present, motivation should become extrinsic. There is a third factor that can influence overall task motivation: the individual’s own ability to diminish the importance of extrinsic constraints. This last point can be an important one, and I will return to it later.

Each of the three components must be present for creativity to emerge. The higher the level of the three components, the high...

Table of contents

- Cover

- List of Contributors

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part One: Research

- Part Two: Practice

- Part Three: Looking Ahead