- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

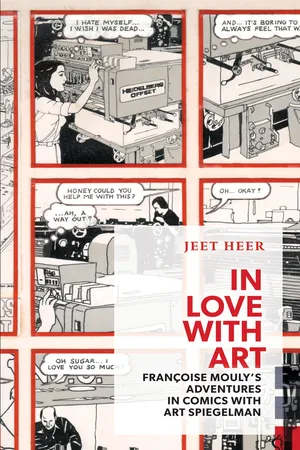

About this book

In a partnership spanning four decades, Francoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman have been the pre-eminent power couple of cutting-edge graphic art. From Raw magazine to the New York, where she serves as art editor, Mouly and Spiegelman have revolutionized the art. In Love with Art profiles the pair and interviews Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, Adrian Tomine and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In Love with Art by Jeet Heer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Artist Monographs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

8

Pictures of Pictures

On September 11, 2001, after witnessing an airplane crash into one of the Twin Towers, Françoise Mouly faced two imperative tasks: first, she had to find her kids, and then she had to come up with a New Yorker cover to somehow mark the event. That day, Mouly and Spiegelman were walking out of their SoHo loft, just ten blocks north of the World Trade Center, planning on voting in the city’s Democratic mayoral primaries, when they saw the first plane hit the North Tower. Mouly initially assumed it was an accident, a leisure plane going off course maybe – it was the only thing that made sense. What she calls her ‘journalist’s instincts’ kicked in, and she called David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker since 1998, and told him to turn on his TV.

Fourteen-year-old Nadja had just started classes at Stuyvesant High School, four blocks from the towers. Worried that debris might land on the school, the anxious parents rushed to find her. Locating her wasn’t easy – the ten-storey school building housed more than 3,500 students. While they searched, Spiegelman overheard a Spanish-language report from a janitor’s radio saying that the Pentagon had been attacked. Then the lights went out, and the building trembled from the collapse of the South Tower. Spiegelman was sure they would all die in the school. After continuing to search for an hour and a half, they found Nadja. As they were leaving Stuyvesant, the North Tower crumbled behind them.

Their daughter in hand, the couple then raced to find their ten-year-old son, Dash, who attended the United Nations International School further uptown. ‘I was willing to live through the disaster wherever it took me, as long as we were all together as a family unit,’ Spiegelman later explained to the New York Times. Once Dash was recovered and the family was safely ensconced in their loft, they checked their messages. Among various reports from friends on their safety, Mouly says, there were also ‘messages from the New Yorker saying, “Get your ass over here. We want to do a cover.”’

Spiegelman, then a staff artist for the magazine with many covers under his belt, went to work in his studio, a few blocks from their loft. The next day, Mouly found a friend to stay with the kids and went into the New Yorker’s midtown office to face the impossible task of coming up with an appropriate cover. She remembers thinking, ‘I want no image. I can’t do this. No image can do justice to this.’ Mouly explained her dilemma to a neighbour, a fellow mother, who responded by saying, ‘What, you have to go to work to do a magazine cover? That’s ridiculous! I’ll tell you what you do: no cover.’

Spiegelman, meanwhile, was making an image that contrasted the lovely fall weather of that day with the horrible event that happened, with the towers covered in a Christo-like black shroud against a Magritte-style blue sky. Every time he walked between his studio and the loft, Spiegelman would look where the towers had stood. Like a phantom limb or a ghostly presence, they were both there and not there, felt but invisible. Remnick, for his part, was considering the use of a photograph – it would have been the first time in New Yorker history and a precedent-breaking way to register such an immense historical event.

Neither idea appealed to Mouly. She still felt that no image – painting, drawing or photo – could do justice to what she and the rest of New York had just experienced. She had another idea: what about an all-black cover? A cover that, as per her neighbour’s argument, wasn’t a cover. Spiegelman wanted his image to run but thought that if the New Yorker was going that route, it should be combined with his own suggestion: how about a silhouette of the towers against a black background, black on black? ‘That actually felt like the most creative solution,’ Mouly says now. She drew up a cover based on their ideas. ‘When I saw it, even before I presented it to my editor, I was like “Oh my god, this actually is the answer, the negative answer, to what I was looking for because it is such a strong statement.”’

When she showed Remnick the image, he asked who did it. Even though she had drawn it, Mouly, driven by her desire to see the image published, didn’t want to admit she’d done it – she was worried because she wasn’t a ‘name’ artist. Besides, the New Yorker’s tradition at that time was not to give collaboration credits on covers. (Mouly changed that later in 2001, giving dual credit to Rick Meyerowitz and Maira Kalman for ‘New Yorkistan,’ thereby establishing a new precedent.) Unprepared for an answer, and used to contributing her ideas to the artists she worked with, Mouly gave Spiegelman the credit – it was his idea, after all. Initially, Spiegelman didn’t want to put his name on it. As he explained in an interview with a New York public television station, ‘It was only when I saw the proof that I went, “Oh, gee, I had nothing to do with that, but it’s really good.” So I don’t feel like I made it. It was just sort of a product of trying to assimilate those two days.’

There were a few last-minute hitches before the cover ran. Late Thursday night, rumours circulated that another magazine might also be doing a black cover. Mouly argued that her cover wasn’t just black but contained a subtle image that set it apart. Fortunately, word came back that the other weekly was going with a photo cover. By Thursday, Mouly finally had Greg Captain, her trusted prepress expert, on the premises. Because of the subtle effect the cover had to achieve, Mouly scrambled to work with her prepress crew to make sure that the ink densities were sufficiently different to capture the contrast between the two almost identical shades of black. The prepress work was made more complicated by the fact Captain had been in Chicago on 9/11; because flights were cancelled after the terrorist event, Captain had to drive back to New York to help solve the technical problems. Then, on Friday morning, he drove the almost fifteen hours to the printer in Kentucky with four versions of the cover, watching the press all night to make sure it worked before driving back.

The 9/11 cover is now among the most famous images in the history of the New Yorker and one of the few lasting works of art to come out of the destruction of the Twin Towers. The image works almost like an optical illusion. At first glance it does seem to be all black. Only when you catch the cover at a certain angle do the dark shapes of the Twin Towers emerge from the inky background. ‘Once you saw it, it was like a ghost,’ Mouly explains. ‘It captured this kind of disconcerted feeling. Everyone was lost and so was I. I was lost in a land where there could be no image. The fact that this negative image still managed to be an image was what really reconciled me to what I do. It showed how powerful simplicity of means could be.’ Art Spiegelman was the President of the Angoulême Comics Festival in 2012 (in effect, a guest of honour who helps organize the show and is celebrated with a special exhibition). When the origins of the 9/11 cover were explained to the French Minister of Culture Frédéric Mitterrand, who was looking at a large-size print, he responded by calling it ‘une idée de génie.’ It’s true that the idea is genius, but so is the execution. It was a true example of collaborative art. Many of the hallmarks of Mouly’s tenure as New Yorker art editor, where she’s been since Brown hired her in 1993, can be seen in the 9/11 cover, including a direct engagement with current events – an enormous tonal shift in New Yorker cover history. But the cover doesn’t deal with this tragedy in the didactic manner of, say, a political cartoon, but rather through artful means: using subtlety and ambiguity, strong design, a compelling use of colour (or in this case, a memorable absence of colour) and the distillation of experience (rather than ideas or ideologies) into an iconic image. The dialogue between Mouly and Spiegelman was also typical of the strongly collaborative way she always has worked with, and continues to work with, her artists.

‘Françoise’s development as a really close editor is something that happened over a period of decades,’ Spiegelman says. If RAW was Mouly’s editorial training ground, the New Yorker has been the publication that allowed her sensibility to flourish and reach a mass audience. She’s arguably had a bigger impact on the face the New Yorker presents to the world than anyone since its founding editor, Harold Ross.

Mouly joined the New Yorker as part of a general regime change under the leadership of Tina Brown, who became in 1992 just the fourth editor-in-chief in the magazine’s entire history. Ross founded the New Yorker in 1925 as a light-hearted humour magazine and over the course of the Depression and Second World War, he slowly transformed it into a more serious journalistic and literary journal. Upon Ross’s death in 1951, William Shawn, who had already made his presence felt as an assistant editor, assumed control of the magazine. During Shawn’s long incumbency, the New Yorker became the premier American showcase for both fiction and long-form journalism, and at its zenith in the 1960s published the first versions of such classic works as James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood as well as stories by John Cheever, Mavis Gallant and John Updike.

By the 1970s, however, Shawn’s New Yorker was suffering from the doldrums of middle age. Shawn’s aversion to anything that smacked of commercialism or sensationalism led to some long-winded pedantry and a milquetoast, genteel detachment. In 1984, Michael Kinsley, writing in the New Republic, attacked Shawn’s New Yorker for its ‘smug insularity, its tiny Dada conceits passing as wit, its whimsy presented as serious politics, and its deadpan narratives masquerading as serious journalism.’ Kinsley was particularly dismayed by a lengthy article about corn. ‘It’s the first in what appears to be a series, no less, discussing the major grains,’ Kinsley complained. ‘What about corn? Who knows? Only the New Yorker would have the lofty disdain for its readers to expect them to plow through 22,000 words about corn (warning: only an estimate).’ In 1990, Louis Menand, writing also in the New Republic, amplified this accusation by noting that under Shawn the New Yorker had become a self-parody, ‘running things like E. J. Kahn’s enormous multi-part series on corn, soybeans, potatoes, rice; publishing reviews of unnoticed books months or years after they had come out; letting topical reports from Washington and reviews of Hollywood movies of no special moment run to tens of thousands of words; serializing the memoirs of the childhoods of New Yorker writers.’

Shawn was famously soft-spoken, so polite and indirect that listeners had to strain to decipher his words. This hushed manner set the tone of the magazine and particularly the covers. Under Harold Ross, the magazine had featured observational cartoon covers that captured the tone of Manhattan life, ranging from the flashiness of 1920s nightlife to the visible economic disparities of the 1930s and shared anxieties about the Second World War. Shawn, on the other hand, preferred serene, bucolic non-narrative covers. As he explained in a 1983 note to the New Yorker’s advertising department, ‘We have fewer covers that have humour than we did years ago. They tend to be more aesthetic and the subject matter of the most part is New York City or the country around New York City. The suburbs, the countryside. Sometimes it’s just a still-life of flowers or a plant. It’s not supposed to be spectacular. When it appears on a newsstand, it’s not supposed to stand out. It’s a restful change from all the other covers, I’d say.’

John Updike, in his introduction to The Complete Book of Covers from The New Yorker, a coffee table book published in 1989, noted that Shawn-era covers tended toward the ‘chastely inhuman’ with many covers from the seventies and eighties depicting ‘dehumanized landscapes, ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About This Book

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Author’s Preface

- The Invisible Woman

- A Surgeon’s Daughter

- A Second Birth

- Spiegelman’s Bicoastal Blues

- Comix 101 with Art Spiegelman

- Postponed Suicides

- Raw Revolutions

- Cover Gallery

- Pictures of Pictures

- Full Circle: Comics for Kids

- Works Consulted

- Image Credits

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- About Exploded Views

- About This Edition