- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

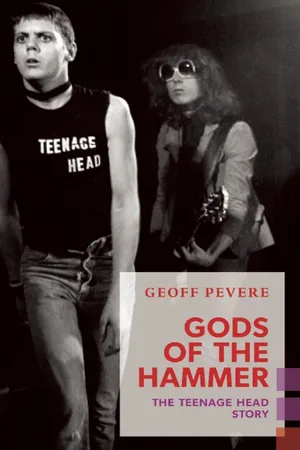

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, no Canadian band rocked harder, louder or to more hardcore fans than Teenage Head. This high-energy quartet – consisting of four guys who'd known each other since high school – were a balls-to-the-walls sonic assault. And they almost became world-famous. Almost. This is their story, told for the first time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gods of the Hammer by Geoff Pevere in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Heart and the Machine

Gord Lewis was lucky to live. He was bedridden for months, and faced extensive physiotherapy to regain mobility. But there was never any question, at least in his mind, that as soon as he was able to get up, pick up his guitar and play again, he would return to Teenage Head.

But it wasn’t going to happen quickly. If there was any thought of putting the band, already performing up to six nights a week, on a well-deserved hiatus, it didn’t get much traction. Within a day or two of the accident, Morrow was appealing to the rest of the band’s sense of obligation to Lewis. The band had to carry on, he argued, so that the bedridden Lewis could continue to be paid while laid up. And besides, there was a shitload of upcoming gigs booked, Frantic City was still selling and the band was more famous across the country than ever. The machine might have lost its heart, temporarily, but what machine ever needed a heart to run?

Mahon: ‘It just hit me when Jack said that, “We gotta pay Gord. We have to keep playing.” So that was like, all right, what else could I do? I was doing fuck all. I was sitting in my apartment.’ It might not have been the right thing to do, but framed as a bid to aid a bedridden friend, it certainly felt right.

Stipanitz was also reluctant to carry on without Lewis, but ultimately agreed. ‘That accident certainly stopped the momentum,’ he says. ‘I think we were headed for an American record deal but that put the brakes on all of that. I didn’t want to play until Gord was well, but Jack convinced us all that we should. We had to pay the rent. I was naive, and at first I didn’t think it was that big a deal: “Oh, he’ll be up next week.” But when it sunk in that it was going to be months, we reluctantly went back out. And just went through the motions. It certainly didn’t sound the same. We always got a lot of energy off of Gord’s playing. We fed off each other.’

Stipanitz was also privy to something Morrow had told him, a bit of on-the-down-low info that might have contributed to the drummer’s sense of solidarity with the band: Teenage Head’s manager had been approached by more than one major label with an interest in signing Frankie Venom as a solo act. No Teenage Head, just Frankie, and Frankie had quietly turned it down: no Teenage Head, no Frankie Venom. He wasn’t going to abandon his band for the sake of fame. It was all of them or none at all.

Morrow replaced Lewis with David Bendeth, an accomplished jazz musician, session player and studio recording professional. His resumé, in fact, was irreproachably impressive in just about every area save the one in which he was being enlisted to perform – as a rock guitarist. But there wasn’t any time – booked gigs are booked gigs – and Bendeth was available. He joined the band, learned the basics of the songs and within days was onstage as the new lead guitarist for Teenage Head.

‘He was completely the wrong guy.’ Mahon says. ‘Like, oh my god. You’re going to pick some jazz player to go in a punk band? He couldn’t get the simplest songs. It wasn’t like he was playing all the wrong chords or something, and he got through it, but man, we really missed Gordie.’

Morrow had known Bendeth a few years and knew he was a skilled musician. That he might not have been the most appropriate one didn’t matter. Bendeth was available and could do the job. Not remotely interested in or acquainted with punk rock or Teenage Head’s music, Bendeth nevertheless learned the basics quickly. But he never fully embraced the music, and if there was one thing that drove Mahon, Stipanitz and long-time friend and sideman Dave Desroches crazy, it was the apparent condescension with which Bendeth did the duty. To them, Bendeth was above the music and never let anybody forget it.

Technically, Bendeth’s performance with Teenage Head was immaculate: he knew all the right notes to play and when to play them, he grew increasingly comfortable onstage, and he actually developed a camaraderie of sorts with the tempestuous and impulsive Frank, with whom he was always bunked while on the road. But he was no Lewis and he knew it. Even his Stratocaster, to some observers, was wrong: Teenage Head was a Les Paul band. This was Gord’s band, Gord’s music and Gord’s dream. Bendeth was just visiting, and he never lost sight of his jacket on the hook at the door. As soon as Gord could, he’d be back.

If the accident provided Lewis with one opportunity he’d been lacking for the previous three years, it was an opportunity for reflection, and on his return it was evident he’d done a lot of thinking about Teenage Head: about what the band had become and how, and whether the fame that was finally theirs was clarifying or clouding that original dream. These were thoughts that must have been acutely pressing as he watched the machine keep rolling even in his absence. If his dream could carry on without him, maybe it had become something with an inorganic life of its own. Was it running away like that kid who’d grabbed his guitar at Ontario Place? And was anybody going to run after it and retrieve it this time, besides him?

Lewis was ready to slowly reintegrate into the band by the end of 1980, a truly remarkable recovery. At first he’d only appear as a special guest doing a number or two, but gradually he resumed his full position as lead guitar. But maybe not his full former energy – he tended to stand more still while playing, to seem less possessed by the channelled currents of the music’s energy than intensely focused on it. But even if he presented differently after the accident, his playing was still unmistakably and blisteringly his. If Bendeth had played Teenage Head’s music and played it well, Lewis was the reverse: the music, his music, played him.

Lewis remembers a distinct change in the atmosphere when he returned to Teenage Head. The rolling on of the machine in his absence had generated something he’d never seen with his band before: a sense of obligation. For the first time, they seemed to be doing this as a job.

‘I kept telling myself I was going to get better and join the band,’ Lewis says. ‘I had no idea I was going to be out of commission for half a year. I knew the band had lost its momentum. I knew things were going to be a little weird, especially when I had to make a gradual comeback. And I didn’t feel very comfortable – I felt like an outsider. Frank was the nicest to me. Frank was the one who made sure I got in and out of the van okay, and walked me to wherever I needed to be walked to. He did really did care. He really, really watched out for me.’

Prone to feeling outside of things anyway, for the first time Lewis felt separated from his band. As much, in fact, as he had when he was laid up in hospital. The perceptible drop in enthusiasm, fun and energy in the band could even be seen in Venom, who had begun complaining of boredom, pointlessness and the same-old grinding same-old.

‘It really changed for Frank,’ Lewis says. ‘Frank was a pretty heart-and-soul guy and I think he could see that Bendeth wasn’t Teenage Head material and wasn’t the guy Frank wanted standing stage left to him. He had to put up with that for three months, and I think he got tired.’

He was, and he wasn’t making any efforts to hide it. On New Year’s Eve, 1980, City TV’s The New Music – hosted by future CNN anchor J. D. (now John) Roberts – went to Headspace to interview the band about the Gordless months. Lewis was there, still in his brace and sitting next to Venom, when Roberts asked the singer what it had been like playing without his friend. Venom, with characteristic Frankness, responded, ‘It’s been good but we haven’t been doing the gigs that we should be doing. We’re just treading water now. We’re not making any waves at all. We’re just making the money.’

Lewis returned to a gigging regimen that was almost as gruelling as the one he’d left – at first, he could only stand onstage long enough for a song or two at a time – and he was also staring the next Teenage Head album right in the spindle hole. It was time to get back into the studio for number three, which meant writing new material – with a tired band – on top of re-entry into the live rock orbit and trying to find the old spark.

The third album would be called Some Kinda Fun, and the title, behind the scenes anyway, was as ironic as Frantic City was genuinely descriptive. Even the cover gave it away: in place of the bubblegum-tinted brightness of the first two albums, with their depictions of the band in a state of high goofball frenzy, Some Kinda Fun showcased the band, unsmiling and shot against blackness from slightly above, looking for all the world like four guys about to processed in county lock-up.

The songs didn’t come easily – although one classic, the hoser-hedonistic anthem ‘Teenage Beer Drinkin’ Party,’ would here be born – and they returned to working with a producer (former Guess Who recording engineer Brian Christian) who some claim didn’t give a shit. It also didn’t help matters that Morrow had convinced the band it was time to split with Attic. Album or no album in the works, potential costs of disengaging from a binding legal contract notwithstanding, and the dubious strategy of alienating your (soon-to-be-former) label just as you’re working on an album that label will subsequently be left to promote, Morrow and the band went ahead and pressed the separation from Attic.

Morrow’s reasoning wasn’t his alone. It was largely shared by the band. Frustrated that they hadn’t yet broken into the States and worried that their golden moment might be flickering past, Teenage Head was growing bullish on the issue of out-of-country exposure. And it was one of the first questions everybody asked them: When are you going to the States? When are you going to Europe? Why are you still playing these fucking bars and shit in southern Ontario?

It was a climate that infiltrated the Some Kinda Fun sessions as well. Stipanitz remembers that the old sense of all-for-one collaboration was gone. He remembers Lewis bringing finished songs to the studio for the first time, a fact that might be attributed to the guitarist’s months recovering from the accident more than any deliberate attempt at seizing control, but it felt like that nevertheless. The band was frustrated, tired and uninspired. They weren’t connecting with their producer and were pissed with their label. Some kinda fun indeed.

Accounts vary on what precisely transpired in Morrow’s negotiations with Attic. According to the band, Attic wasn’t doing enough to get the band into the U.S. According to the former heads of Attic, Morrow was making unreasonable demands that contravened their original agreements. Both Mair and Williams insist that getting the band into the States was indeed a priority, but that it would take time, and time was something neither Morrow nor the band were willing to spare. None of this was making the vibe in the studio any better. At one point, relations between Teenage Head’s management and their label grew so tense that Attic had an armed guard posted at the studio door to prevent anyone from stealing the masters. No wonder the boys look so pissed on the cover.

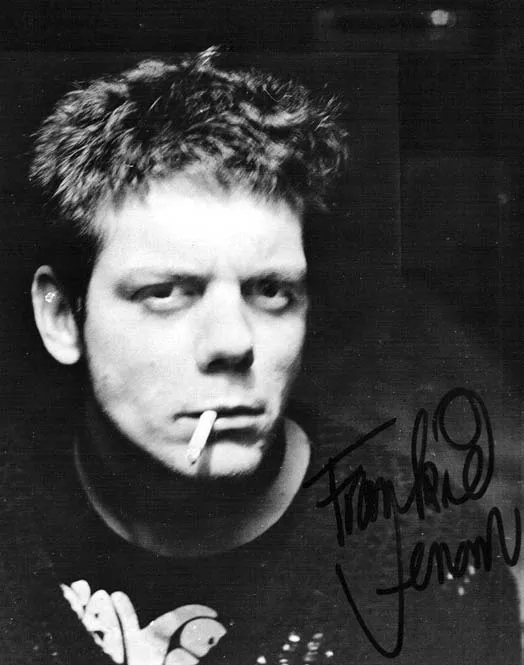

Frank, 1979.

‘I don’t recall the exact timing of when we decided to let them go,’ Mair says, ‘whether it was before or after the album came out. But I suspect in hindsight that letting them go had some impact on our interest in them, because we weren’t going to have their next album. Maybe we were guilty of not promoting it as 110 percent as we had the first record, but it didn’t do as well as Frantic City.’

Mair didn’t trust Morrow. He was making what the former now calls ‘ridiculous demands’ and playing games. The album was finished, but he refused to deliver it. And all the money went thr...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- About This Book

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: The Endless Party

- Picture My Face: Monkee Planet

- Hammered

- The Basement Years

- Star Time

- Punk? Yeah. Sure. Why not?

- 1978–1979: The Sweet Spot

- In the Company of Wolves

- The Grit and the Glory: Into the Studio

- Machine Head

- Frantic

- 1980: Crest and Break

- The Heart and the Machine

- What Can a Poor Boy Do?

- Afterword

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Photo Credits

- About Exploded Views

- About This Edition