eBook - ePub

Any Other Way

How Toronto Got Queer

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Any Other Way

How Toronto Got Queer

About this book

Toronto is home to multiple and thriving queer communities that reflect the intense diversity of the city itself, and Any Other Way is an eclectic history of how these groups have transformed Toronto since the 1960s. From pioneering activists to show-stopping parades, Any Other Way looks at how queer communities have gone from existing in the shadows to shaping our streets.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Any Other Way by Stephanie Chambers, Jane Farrow, Maureen Fitzgerald, Ed Jackson, John Lorinc, Tim McCaskell, Rebecca Sheffield, Tatum Taylor, Rahim Thawer, Stephanie Chambers,Jane Farrow,Maureen Fitzgerald,Ed Jackson,John Lorinc,Tim McCaskell,Rebecca Sheffield,Tatum Taylor,Rahim Thawer, John Lorinc, Tim McCaskell, Maureen Fitzgerald, Jane Farrow, Stephanie Chambers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Rupert Raj

Worlds in Collision

A gender-distressed teenager of nineteen, I transitioned from female to male in the Nation’s Capital in 1971, three years after my parents died in a car crash. I was a Carleton University psychology student, and my academic career coincided with my gender transition and my trans activism. Blazing the trail for other transsexuals across Canada and the United States from then until now, I have seen a lot of shit go down in the transgender and cisgender (non-trans) worlds, and in straight and queer scenes alike. This essay will give you a glimpse of some safe and unsafe spaces, and some good and bad times, of trans and queer life in the early days of Toronto, the world’s most diverse city – and one of the trans-/queer-friendliest.

Community Centres (58 Cecil Street and the 519)

Before the 519 Church Street Community Centre became the heart and soul of the Gay Village in 1975, there were no queer or trans community centres in Toronto, despite the efforts, in 1972, of the Canadian Homophile Association of Toronto to turn 58 Cecil Street into such a venue. Cecil Street was also home to the Association of Canadian Transsexuals, Canada’s first trans group, formed in 1970 by three transsexual women: Diana LaMonte, Lynne Pellerin, and ‘Louise’ (a pseudonym). I first met Louise in the summer of 1972, driving down Highway 401 in my new, shiny-red Toyota Corolla. I’d recently started testosterone therapy (‘T’) and was raring to go, desperate to seek out other trans folks.

The 519, in those days and now, was a hub for the trans and queer communities – typically worlds in collision. I co-founded and led three trans groups: FACT Toronto (a local chapter of the Foundation for the Advancement of Canadian Transsexuals, 1979-86), Metamorphosis Medical Research Foundation (1982-88), and the Trans Men/FTM Peer-Support Group (1999–present). FACT Toronto became Transition Support, one of the longest-running trans groups in Canada. The Trans Men/FTM group petered out (pun intended!) not long after I left, but I’m working to persuade the 519 management to fund a group for older trans guys (forty-plus) and their loved ones and allies.

‘Jurassic Clarke’ (The Clarke Institute of Psychiatry)

Gendercide, a term I coined for the erasure of trans and gender non-binary people, generates trauma. In the 1970s and 1980s, Dr. Betty Steiner, the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry’s Adult Gender Identity Clinic’s chief psychiatrist, loftily claimed there was no such thing as female-to-male transvestites (although she conceded the existence of male-to-female cross-dressers). Tongue-in-cheek, I informed my three female cross-dressing friends that according to modern psychiatry, they were only figments of their ‘self-deluded’ imagination. ‘Control queen’ Steiner also put the kibosh on a potential extension of the Clarke’s one-year pilot program to recommend Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) coverage of phalloplasty (penile surgery) for female-to-male transsexuals (trans males/trans men), categorically deciding this form of ‘bottom’ surgery was ‘too experimental,’ given the limited outcomes back then, and despite the stated relative satisfaction of many of the trans guys. So much for patients’ ‘informed choice.’

Betty also chose not to notify her trans-male patients of my gender-consulting service (Metamorphosis) because it wasn’t OHIP-insured and she didn’t want them to have to pay out-of-pocket. This was an unwarranted withholding of a valuable, unique resource, given that I was the only game in town for trans men at the time. Clarke psychologist Dr. Ray Blanchard was equally exclusionary, smugly informing Lou Sullivan, an ‘out’ gay trans man, that he didn’t fit the classic typology of sexual or gender types for ‘(born) females,’ meaning his identity couldn’t be ‘authenticated.’ Blatant transqueerphobia! And if you happened to be a femmy T-boy, genderphobia ran rampant!

Our trans sisters were similarly pathologized. In the early days, T-girls were denied approval for sex hormones or genital surgery if they identified as lesbian or bisexual, thereby closeting trans dykes and trans bis for many years. (The Clarke clinicians reluctantly conceded the existence of trans lesbians and bisexuals in the 1990s, but it took them nearly another decade to similarly ‘tolerate’ trans gay men and bis. Reverse sexism!)

Male-to-female transsexuals (trans females/trans women) seeking sex-reassignment surgery (a.k.a. gender-confirming surgery) had to dress in überfemme attire (no butch or tomboy T-girls allowed!). Those married first had to get divorced because the Clarke feared potential lawsuits from wives resenting the (perceived) ‘emasculation’ of their husbands. Psychiatrists’ paranoia or what? To add insult to injury, a number of these patients were (voluntarily) subjected to Dr. Kurt Freund’s controversial phallometer (a.k.a. penile plethysmography), an electronic device measuring penile responses to photographs of children, gay men, and males dressed in female clothing, respectively. The goal: to determine if they were adult sex offenders, pedophiles, effeminate gay men, transvestites, or transsexual women. Righteously enraged, one trans woman exclaimed some years later, ‘They fried my penis!’

Fortunately, I escaped the clutches of the Clarke’s gender clinicians until 2011, when, approaching sixty, I applied for OHIP approval of metoidioplasty (another form of genital surgery for T-boys). Thankfully, I came through the screening process unscathed, due to a new transpositive clinical staff headed by Dr. Chris McIntosh, a psychiatrist, and Dr. Nicola Brown, a patient-friendly psychologist.

Sex Clubs (Black Eagle, Tool Box, Spa Excess, Pussy Palace)

Although I rarely went to sex clubs, I did check out the Black Eagle and the Tool Box (bathhouses for queer men) on occasion, but never made it inside the Pussy Palace. There were no trans-specific sex clubs until trans sex worker/porno star Mandy Goodhandy and pro dom/porno producer Todd Klinck co-founded Good-handy’s in 2006, at 120 Church Street. Alternatively called a ‘pansexual playground’ and a ‘tranny bar,’ it catered to ‘tranny chasers’ (mostly men turned on by transgenderists and presurgical trans women). Most trans people, including me, disparage the trashy ‘tranny’ label as commodifying and offensive. Of course, before the 2000s, cis gay male bathhouses excluded known trans men; it’s questionable, even now, if they’re truly trans-male inclusive. ‘Transqueerpositivity’ is taking its sweet time!

Queer Churches (Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto)

Sexuality and spirituality are both important human needs. When I first arrived here in 1979, I asked Rev. Brent Hawkes, pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto, if he thought I had a hope in hell of finding a cis gay male lover, given that I hadn’t yet had ‘bottom’ surgery. I don’t recall his exact words, but he was encouragingly transpositive (a rarity in cis gay men back then) and welcomed me into his Christian church for queers and our allies. Other gay, lesbian, bi, and trans-affirming ministries soon followed: Dignity and Christos (both Catholic), Integrity and the United Church (both Protestant), the Universalist Unitarian Church (non-denominational), Dharma Sitting (Buddhist), and later, in the 1990s, Queer Muslims, Trans Jews, neo-pagan covens (many trans women are witches, and some trans men warlocks, preferring the goddess religions), and interfaith groups.

These spiritual havens kept us somewhat safe from homophobic or transphobic fundamentalist religionists. I met a post-transitional trans woman who soon after ‘detransitioned’ to their natal (male) sex because of a rejecting Christian fundamentalist mother. He wanted to join my Metamorphosis group ‘to learn how to be a man again.’ Regretfully, I advised that the group was only for (female-born) trans males, so ‘he’ married a strict Christian and now lives the life of a God-fearing, straight, cis man. What a price to pay for the right to be who we are!

Then and Now …

Nearly half a century after I transitioned, we’re finally starting to move beyond societal genderphobia, community infighting, and gender policing, with promising examples of collaboration across all spheres in Toronto and Canada. Working together across cisgender and transgender, straight and queer spaces, and all of society’s institutions, we must continue to bridge our diverse communities, forming sustainable partnerships, locally and globally. As effective allies, we must fight against all forms of violence (anti-indigeneity, racism, classism, sexism, genderism, ageism, ableism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, trans misogyny, trans misandry) to ensure a safer city and world where we can all live, work, and play together.

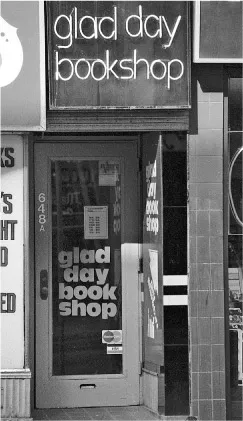

Jearld Moldenhauer

A Literary Breakthrough:

Glad Day’s Origins

In late January, 1969, I emigrated from the United States to Canada to take a research position at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine. Eight months later, I founded Canada’s first post-Stonewall gay organization: the U of T Homophile Association. Soon after, The Globe and Mail published a letter criticizing U of T for formally recognizing the UTHA. I wrote a letter in response, and was fired shortly after The Globe published it.

I travelled for several months and then returned to Toronto, immediately re-involving myself in the city’s three gay organizations.

The sheer number of new and used bookstores had always made me feel happy to be a Torontonian. Books had played a central role in my own life – not just those about the subjects that interested me, but also those that allowed me to overcome my own self-oppressed mentality about being gay. French writer André Gide and American sex researcher Alfred Kinsey were crucial to my developing a positive image of myself as a homosexual. I felt that the power of books offered the prospect of advancing social democracy, especially in literate but oppressively backward societies such as the U.S. and Canada.

After Stonewall, publishers started to issue books about gay and lesbian life, written by a generation of newly ‘liberated’ homosexuals. This literary breakthrough began to combat the traditionally negative images of homosexuality – often defined by disease and sickness – that dominated the literature of the time. While Toronto served as the centre of Canada’s publishing industry and had an abundance of bookshops, I could never find copies of these new releases, even though most were being reviewed by the New York Times and The Village Voice.

As I learned, Censorship needn’t be overt. Rather, I noticed widespread, internalized self-censorship, driven by forces seeking social conformity to community standards, insidiously reinforcing the status quo. Toronto’s webs of power wanted to protect and thereby sustain the existing class structure.

Censorship – conscious and unconscious – was of utmost importance to those who might find their status altered by new ideas or new ways of looking at old ideas. The perception and experience of human sexuality is a culturally based reality that changes from one society to another, and from generation to generation. Queers were situated at the bottom of that pecking order, subjected to propaganda in every form of media, including the advertising of heterosexual status as it directly related to the purchase of consumer products. The sustenance of that order also depended on traditional state power, superstitious religious authority, and pseudo-scientific psychological theory.

My response to the backwardness of Toronto’s bookstore scene began with a few phone calls to publishers to find out how one could order books at wholesale prices. I didn’t aspire to become a businessman, but I wanted to make this new gay literature available to the Canadian public. From my inquiries, I realized that if existing bookshops were afraid to breach the barrier, then I could … and would. And so I started Glad Day late in 1970.

Gay books and periodicals were vital tools for communicating with individual gay men and lesbians who had not yet formed a community. As queers, we grow up isolated (even from each other) and often in hostile environments. Literature provided the path to raise the political and social awareness of our oppression and our common identities. By sharing our stories and ideas, we could emerge as a community determined to not only claim our rightful place in society but also take control of our future.

It was easy and inexpensive to enter the book trade in those days: minimum orders were low and you were given ninety days’ credit. For all its aspirations, Glad Day began as a kind of mobile bookshop. For the first few months, I packed up the books that arrived at my apartment in my backpack and rode my bike to the meetings of Toronto’s three gay groups: UTHA, the Community Homophile Association of Toronto, and Toronto Gay Action. The more catalogues I ordered from publishers and distributors, the more new titles I discovered, as well as older books of historical importance.

I then began to compile the titles and print copies of my own little catalogue. I also advertised my book service in a weekly scandal rag called Tab, a sensationalist newspaper full of mostly heterosexual titillation. It contained a few gay-oriented news stories and was the only cross-country print media that would accept an ad from a self-identified gay bookseller. (In 1974, Glad Day filed a complaint with the Ontario Press Council against the Toronto Star and, in 1985, another against the Globe and Mail, for refusing to accept our advertising. Glad Day won both cases, and those adjudications were among the first victories in the struggle for equality.)

My little classified ad brought inquiries and requests from all over Ontario and beyond. It also brought my first seriously supportive customer: Jean-Raymond St-Cyr, director of the French CBC Radio in Ontario, and the father of Star columnist Chantal Hébert. St-Cyr encouraged my efforts (especially when it came to French writers) and bought more books than any other long-term customer. (He remained supportive of Glad Day until his death in 2007.)

Late in 1971, my roommates bought a house in Kensington Market with a plan to create an art gallery on the ground level and use the second floor as our apartment. They agreed to let me occupy an unheated shed at the rear as both a bookshop and an office/workspace for The Body Politic, the gay newspaper I founded. During those first few years, I considered Glad Day and TBP to be complementary projects. Book sales provided me with a subsistence living while allowing me to help run an alternative paper.

In the summer of 1972, TBP experienced its first crisis after we published Gerald Hannon’s feature on intergener...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- ‘A New Way of Lovin”: Queer Toronto Gets Schooled by Jackie Shane

- Arriving

- Spaces

- Origins

- Demimonde

- Emergence

- Resisting, Sharing, Organizing

- Epidemic

- Scenes

- Sex

- Rights and Rites

- Pride

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- The Contributors

- The Editors

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits