Chapter 1

Don’t trust your gut

Man prefers to believe what he prefers to be true.

Francis Bacon

Nobody wants to be wrong – it feels terrible. In order to protect ourselves from acknowledging our mistakes, we have developed a sophisticated array of techniques that prevent us from having to accept such an awful reality. In this way we maintain our feeling of being right. This isn’t me being smug by the way. Obviously, I’m as susceptible to self-deception as anyone else; as they say, denial ain’t just a river in Egypt.

There are two very good reasons for most of the mistakes we make. Firstly, we don’t make decisions based on what we know. Our decisions are based on what feels right. We’re influenced by the times and places in which we live, the information most readily available and which we’ve heard most recently, peer pressure and social norms, and the carrots and sticks of those in authority. We base our decisions both on our selfish perceptions of current needs and wants and on more benevolent desires to positively affect change. And all of this is distilled by the judgements we make of the current situation. But our values and our sense of what’s right and wrong can lead us into making some very dubious decisions.

Secondly, we’re deplorable at admitting we don’t know. Because of the way we’re judged, it’s far less risky to be wrong than it is to admit ignorance. If we’re confident enough, people assume we must know what we’re talking about. Most of us would prefer a clear answer, even if it turns out to be wrong, than an admission that someone is unsure. Because no one likes a ditherer, certainty has become a proxy for competence. Added to this, very often we don’t know that we don’t know.

Feeling uncertain is uncomfortable, so when we’re asked a hard question we very often substitute that question for an easier one. If we’re asked, “Will this year’s exam classes achieve their target grades?”, how could we know? It’s impossible to answer this question honestly. But no one wants to hear, “I don’t know,” so we switch it for an easier question like, “How do I feel about these students?” This is much easier to answer – we make our prediction without ever realising we’re not actually answering the question we were asked.

Despite it being relatively easy to spot other people making mistakes, it’s devilishly difficult to set them straight. Early in my career as an English teacher, I noticed that children would arrive in secondary school with a clear and set belief that a comma is placed where you take a breath. This is obviously untrue: what if you suffered with asthma? So how has this become an accepted fact? Well, mainly because many teachers believe it to be true. This piece of homespun wisdom has been passed down from teacher to student as sure and certain knowledge, probably for centuries. If you do enough digging, it turns out punctuation marks were originally notation for actors on how to read scripts. It’s still fairly useful advice that you might take a breath where you see a comma, but it’s a staggeringly unhelpful rule on how to use them.

I’ve spent many years howling this tiny nugget of truth at the moon, but it remains utterly predictable that every year children arrive at secondary school with no idea how to use commas. Teaching correct comma use depends on a good deal of basic grammatical knowledge. It’s a lot easier to teach a proxy which is sort of true. Although the ‘take a breath’ rule allows students to mimic how writing should work, it prevents a proper understanding of the process. And so the misunderstanding remains. As is often observed, a lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth has had time to find its boots, let alone tug them on.

This kind of ‘wrongness’ is easy to see. It’s much more difficult when what we believe validates who we are. Many of our beliefs define us; a challenge to our beliefs is a challenge to our sense of self. No surprise then that we resist such challenges. Here are some things which defined me and which I used to believe were certain:

- Good lessons involve children learning in groups with minimal intervention from the teacher.

- Teachers should minimise the time they spend talking in class and particularly avoid whole class teaching.

- Children should be active; passivity is a sure sign they’re not learning.

- Children should make rapid and sustained progress every lesson.

- Lessons should be fun, relevant to children’s experiences and differentiated so that no one is forced to struggle with a difficult concept.

- Children are naturally good and any misbehaviour on their part must be my fault.

- Teaching children facts is a fascistic attempt to impose middle class values and beliefs.

These are all things I was either explicitly taught as part of my training to be a teacher or that I picked up tacitly as being self-evidently true. Maybe you believe some or all of these things to be true too. It’s not so much that I think these statements are definitively wrong, more that the processes by which I came to believe them were deeply flawed. In education (as in many other areas I’m sure), it would appear to be standard practice to present ideological positions as facts. Like many teachers, I had no idea how deeply certain ideas are contested as I was only offered one side of the debate.

I’ll unpick how and why I now think these ideas are wrong in Chapter 3, but before that I need to soften you up a bit. If the rest of the book is going to work, I need you to accept the possibility that you might sometimes be wrong, even if we quibble about the specifics of exactly what you might be wrong about. You see, we’re all wrong, all the time, about almost everything. Look around: everyone you’ve ever met is regularly wrong. To err is human.

In our culture, everyone is a critic. We delight in other people’s errors, yet are reluctant to acknowledge our own. Perhaps your friends or family members have benefitted from you pointing out their mistakes? Funny how they fail to appreciate your efforts, isn’t it? No matter how obvious it is to you that they’re absolutely and spectacularly wrong, they just don’t seem able to see it. And that’s true of us all. We can almost never see when we ourselves are wrong. Wittgenstein got it dead right when he pointed out: “If there were a verb meaning ‘to believe falsely’, it would not have any significant first person, present indicative.”1 That is to say, saying “I believe falsely” is a logical impossibility – if we believe it, how could we think of it as false? Once we know a thing to be false we no longer believe it. This makes it hard to recognise when we are lying to ourselves or even acknowledge we’re wrong after the fact. Even when confronted with irrefutable evidence, we can still doubt what is staring us in the face and find ways of keeping our beliefs intact.

Part of the problem is perceptual. We’re prone to blind spots; there are things we, quite literally, cannot see. We all have a physiological blind spot: due to the way the optic nerve connects to our eyes, there are no rods or cones to detect light where it joins the back of the eye, which means there is an area of our vision – about six degrees of visual angle – that is not perceived. You might think we would notice a great patch of nothingness in our field of vision but we don’t. We infer what’s in the blind spot based on surrounding detail and information from our other eye, and our brain fills in the blank. So, whatever the scene, whether a static landscape or rush hour traffic, our brain copies details from the surrounding images and pastes in what it thinks should be there. For the most part our brains get it right, but occasionally they paste in a bit of empty motorway when what’s actually there is a motorbike.

Maybe you’re unconvinced? Fortunately there’s a very simple blind spot test:

Close your right eye and focus your left eye on the cross. Hold the page about 25 cm in front of you and gradually bring it closer. At some point the left-hand spot will disappear. If you do this with your right eye focused on the cross, at some point the right-hand spot will disappear.

So, how can we trust when our perception is accurate and when it’s not? Worryingly, we can’t. But the problem goes further. French philosopher Henri Bergson observed, “The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.” Quite literally, what we are able to perceive is restricted to what our brain thinks is there.

Further, Belgian psychologist Albert Michotte demonstrated that we ‘see’ causality where it doesn’t exist. We know from our experience of the world that if we kick a ball, the ball will move. Our foot making contact is the cause. We then extrapolate from this to infer causal connections where there are none. Michotte designed a series of illustrations to demonstrate this phenomenon. If one object speeds across a screen, appears to make contact with a second object and that object then moves, it looks like the first object’s momentum is the cause of the second object’s movement. But it’s just an illusion – the ‘illusion of causality’. He showed that with a delay of a second, we no longer see this cause and effect. If a large circle moves quickly across the screen preceded by a small circle, it looks like the large circle is chasing the small circle. We attribute causality depending on speed, timing, direction and many other factors. All we physically see is movement, but there’s more to perception than meets the eye. Consider how we infer causes to complex events: if we see a teacher teach two lessons we consider inadequate, we infer that they’re an inadequate teacher.

This leads us to naive realism – the belief that our senses provide us with an objective and reliable awareness of the world. We tend to believe that we see objects as they really are, when in fact what we see is just our own internal representation of the world. And why wouldn’t we? If an interactive whiteboard falls on our head, it’ll hurt! But while we may agree that the world is made of matter, which can be perceived, matter exists independently of our observations: the whiteboard will still be smashed on the floor even if no one was there to see it fall. Mostly this doesn’t signify; what we see tends to be similar enough to what others see as to make no difference. But sometimes the perceptual differences are such that we do not agree on the meaning and therefore on the action to be taken.

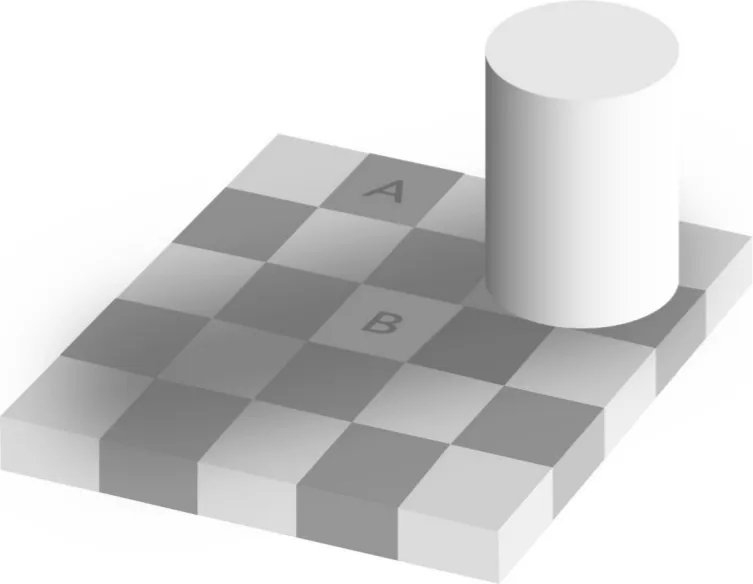

The existence of optical illusions proves not only that our senses can be mistaken, but more importantly they also demonstrate how the unconscious processes we use to construct an internal reality from raw sense data can go awry.

In Edward H. Adelson’s checker shadow illusion (Figure 1.2), the squares labelled A and B are the exact same shades of grey. No really. The shadow cast by the cylinder makes B as dark as A, but becaus...