Evie

Evie arrives at secondary school with the label ‘less able’. She has fallen behind during her primary years in the basics – reading, writing and arithmetic. She is a hard-working, conscientious child from an underprivileged background. She receives little support from home. On arrival at secondary school, Evie takes a number of baseline tests and before long finds herself in the bottom set for many subjects. In unstreamed subjects, teachers differentiate by giving her easier work to complete than her peers. Teachers rarely expect more than this from Evie – after all, somebody has to be the weakest in the group. It is no wonder then that Evie herself has little expectation that she can become an academic achiever. After five years of secondary school, Evie enters the real world. She has failed her GCSEs.

Emma, the English NQT

During her first year as an English teacher, Emma decides to take a risk and teach a poem she has always loved to her Year 9 group, Robert Browning’s ‘Porphyria’s Lover’. It is a sullen Thursday afternoon in late November and the lesson is nothing short of a disaster. The classroom is awash with cries of ‘I don’t get it’, ‘Why do we have to do poetry?’ and ‘Mr Brown’s class next door are watching a video today.’ At last the bell rings for the end of the day, and Emma vows never again to attempt Browning with her Year 9 groups. She will look for an easier alternative next year.

Challenge – What It Is And Why It Matters

Put simply, challenge in education is the provision of difficult work that causes students to think deeply and engage in healthy struggle. It is unfortunate that all too often challenge is presented in the context of ‘challenging the most able’. Evie’s story is an extreme logical extension of this phenomenon. Teachers were only ever expected to support her, never challenge her. Sadly, these low expectations, consciously and subconsciously, were transferred to Evie herself, whose schooling became defined by a lack of self-belief. Fascinating, if controversial, research from Rosenthal and Jacobson in the 1960s, into what they dubbed ‘the Pygmalion effect’, suggests that our expectations of students can have a profound effect not only on how we interact with them but also on the student’s future achievement. They found – and it makes for uncomfortable reading – that teachers in their study would interact differently with those students of whom they had higher expectations. They would be ‘warmer’ towards these children, teach them more material, give them more time to respond to questions and provide them with more positive praise.

It is bizarre, morally questionable even, that we have come to believe that only those we describe as the ‘most able’ need or deserve to be challenged. Some overarching principles are needed to help us to use challenge in the classroom:

♦ It is not just about the ‘most able’.

♦ We should have high expectations of all students, all the time.

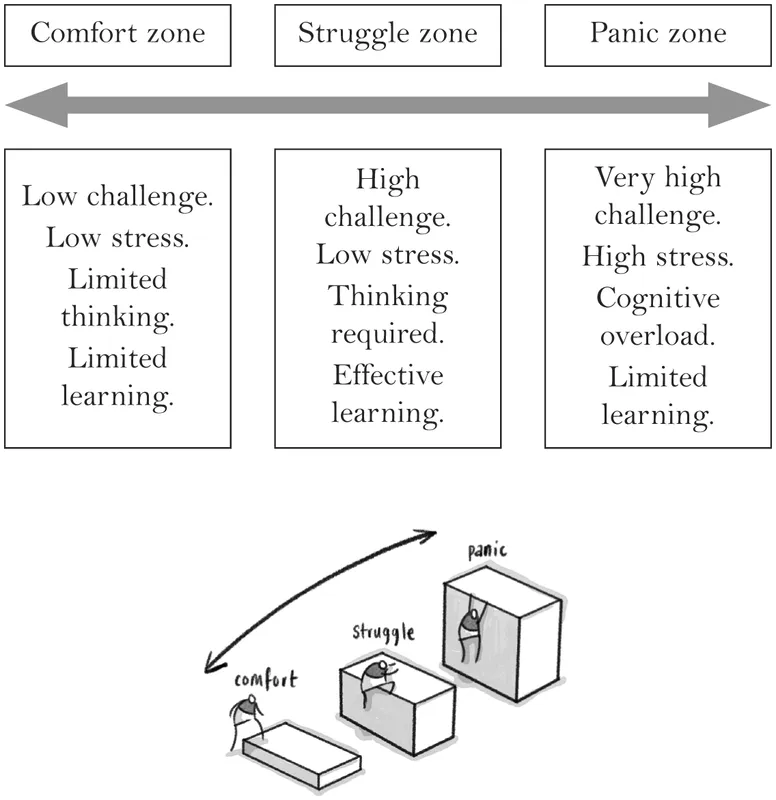

♦ It is good for students to struggle just outside of their comfort zone, as that is when they are likely to learn most.

The first and last points relate to Carol Dweck’s work on mindsets. Those students who adopt a growth mindset are more likely to understand that hard work, effort and learning from failure are vital to their future success. Providing them with challenging work is easy for the teacher; they are likely to embrace it. They will enjoy the struggle and see this as integral to their learning. It is the underachieving, fixed mindset students that cause us most difficulty. To them, effort feels fruitless and seems to compound their negative self-perception. Because they want to be seen as bright at all costs, they do not want to be considered as struggling. The temptation, as a teacher, is to give these students ‘easy work’ for a quiet life. Because the work leads to no real effort or deep thinking, it is very unlikely that they are learning. However, it keeps them satisfied because by completing the work they will not have to lose face through public failure.

Instead, we need to move these students from a fixed to a growth mindset, and the only way to do this is to give them more challenging work and to support them by helping them to believe that they can do it. We want to shift them to a position where, through hard work, resilience and determination, they will eventually embrace the struggle.

Have you ever been told, following a lesson observation, that your lesson was ‘badly pitched’ because students were struggling? This is an odd statement because, within reason, struggle supports learning. A careful balance needs to be struck – as in the figure below. While we want to move students out of their comfort zone into the struggle zone, we also need to ensure that we do not push them too far so that they end up in the panic zone. Hattie and Yates have summarised research showing that useful learning will not occur when there is too much new material for our working memory – the part of the mind responsible for holding and processing information – to cope with. The skill of the effective teacher, therefore, is to push students just far enough so that they are in a productive struggle, but not so far that they drown in a sea of panic.

The second scenario at the beginning of this chapter featured Emma, the NQT English teacher, grappling to teach a difficult poem to an uncooperative class. The students were possibly experiencing cognitive overload or perhaps feigning laziness. The solution here is to reconsider how to teach the poem, rather than to scrap it from the curriculum forever. If ample time is given to teaching the poem step by step, then teaching ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ to the full ability range is eminently possible. The take-away here is that challenge must start at home – with us, the teachers.

So where does this leave differentiation, which is conventionally thought of as the teacher providing students of different abilities with work to match their ‘ability profile’? The figure below demonstrates our solution to the problem of ensuring that needs are met, yet keeping the challenge high.

This model suggests that we should set the bar of expectation high for all students, irrespective of their starting points. Our job, then, is to respond to and support students during lessons, and over weeks, months and years, so that they all strive to reach, or in some cases surpass, this common goal. In doing so, differentiation will lie in the skilfulness of our response to the anticipated and unanticipated difficulties that our students will encounter along the way. This can only work effectively if we understand the individual students we are teaching, we have a deep knowledge of subject content and we know which parts of our subject students tend to find difficult.

For example, imagine your students are writing an essay on Shylock from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. They are five minutes into the task when …

♦ Callum puts his hand up and asks how to spell ‘traumatised’, as he often does with new vocabulary. You tap the dictionary on his desk and smile, but repeat the word for the whole class to reinforce your expectation that students employ challenging vocabulary.

♦ Grace’s hand shoots up. You smile and motion it down. She smiles wryly back, sensing that, once again, you are encouraging her to be more resilient.

♦ ‘Less able’ Katy has not written a thing. You verbalise the first half of a sentence and she finishes it. Then she writes it down and off she goes.

♦ You and your teaching assistant circulate for a couple of minutes armed with highlighter pens. You randomly zoom in on students who are likely to have misspelled words and either highlight them or put a dot in the margin for the student to work out where the mistake is.

♦ On your rounds, you have noticed the clunky overuse of ‘this’ at the start of sentences. You stop the class and explain how they can use ‘which’ clauses (relative clauses) to combine sentences into fluent complex sentences.

♦ You come to Matt, incredibly able but prone to prolixity. He must cut out ten unnecessary words before continuing.

♦ Graham has written a page and a half of scrawled nonsense and is swinging back in his chair. You hand him a piece of paper and tell him to redraft the first paragraph, this time using the paragraph structure you have given him. You sense potential defiance and remind him that it is breaktime after the lesson.

In this scenario, all the students are given the same task, yet your response to individuals is different. These responses are decided not according to preconceived assumptions of need, but to genuine needs as they arise. High expectations are in place because you set the bar high ...