Chapter 1

What is Numeracy?

On occasion, I’ve seen grown adults reduced to a quivering heap by maths. Although this might be an extreme reaction by the unfortunate few, the word ‘maths’ seems to have become almost a swear word for some people. Many maths phobics draw on negative memories of school maths lessons and baffling concepts such as algebra or logarithm tables. Recollections like these are often where lifelong problems with maths begin.

However, there is a real issue in some educational establishments which treat numeracy as the estranged cousin to literacy. The thinking goes that so much of our lives rely on computers and algorithms to do things for us, that a basic knowledge of maths is no longer necessary, and, as such, maths gets placed on the back burner. This has disastrous consequences. The number of people who are innumerate is growing steadily and this needs to be tackled in the early years at school. With qualifications in subjects such as geography and science acquiring heavier maths core skills content, this reason alone should motivate us to embed links to numeracy across the full curriculum.

We live in a culture in which people go to extreme lengths to hide the fact that they can’t read or write. Bizarrely, however, it is deemed socially acceptable to say, ‘I can’t do maths’ or ‘I’m no good at maths’, and then do nothing about it. It’s easy to forget the damaging effects that repeating those simple words to yourself can have on the growing mind; it then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Parents, teachers, celebrities, even movies and advertising campaigns, may often deliberately or unconsciously promote people’s perception that it is okay to be rubbish at maths.

So, how can we expect students and the future leaders of tomorrow to hold maths and numeracy in high regard when society is continually telling them that being bad at maths is acceptable? According to a YouGov poll commissioned by the charity National Numeracy, regardless of the participant’s level of the subject, 80% either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, ‘I would feel embarrassed to tell someone I was no good at reading and writing.’ However, only 56% of people either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, ‘I would feel embarrassed to tell someone I was no good with numbers and maths.’ However, the issue is even more prevalent with females: 82% saying they would feel embarrassed to tell someone, ‘I was no good at reading and writing’ and only 53% saying they would feel embarrassed to tell someone, ‘I was no good with numbers and maths.’ This is a 29% difference with the female sample compared to the male sample, where the difference was only 18%.

In failing to change this culture of ignorance, we are handicapping ourselves for the rest of our lives. No matter how much we might loathe mathematics, we need to acknowledge that we all use it on a daily basis. We are surrounded by mathematical concepts all day, every day. Therefore, we need to change the passive acceptance of failure and find every way possible to support students to overcome their maths hang-ups.

It is the job of the teacher to be not only numerate themselves, but also to recognise and respond to any numeracy weaknesses in their students. It is only in this way that progress will be made, and this has to happen in all areas of the curriculum as well as in everyday life out of school. As a result, students become more competent and are more likely to buy into their learning.

The first part of this process is to make it acceptable to admit to poor numeracy skills, as that is the basis for doing something about it. The acceptance of poor numeracy skills is different from the proud declaration of not being able to do maths which can lead to students who won’t try and who seem not to care. There should be no shame – or glory – attached to a student’s admission. Instead, it should be seen as part of learning to do better, demonstrating a growth mindset and the foundation of future success in life.

Why maths matters

Although it is not possible to be definite about how the working environment will change in the future, we can be certain that it will change, and that some kinds of work will be taken over by automation and artificial intelligence, reducing the amount of skilled and semi-skilled work that we became familiar with in the 20th century.

In other areas jobs will rise. The National Careers Service predicts that ‘Employment in the trade, accommodation and transport industries is expected to increase by 400,000 jobs by 2020. Much of this growth will be in distribution, retail, hotels and restaurants.’ This means that in the future there will be an increasing need for people to work in catering services; social services; sport, leisure and tourism; transport; storage, dispatch and delivery; and retail sales. All of these require numerate workers, capable of measurement, timetabling, costing, statistical analysis, networking, accounting and forecasting. In addition, many people will be expected to be fluent in computer technology and able to write their own algorithmic software programs.

If the UK is to continue to develop economically, then today’s students need to understand the relevance of numeracy, and that unless they are able to participate in future developments in technology, they will find it difficult to get work. Research carried out by Pro Bono Economics, drawing on a number of factors, estimates that low numeracy levels cost the UK £20.2 billion (1.3% of GDP) each year. A massive 68% of employers are concerned about their employees’ ability to understand if the figures presented to them make sense – what is commonly called a ‘sense check’.

So, maths really does matter in the current climate, and for the future if the economy is going to grow and adapt to changes in technology and working practices. As educators, we need to make sure that companies have faith that our young people have a sufficiently high level of mathematical ability, so they remain highly employable in both the national and global market. Improving numeracy within schools is a fundamental way of developing core skills.

Numeracy is the stepping stone that allows students to access mathematics. It is, if you wish, a subset of mathematics. Numeracy is the basic ability to recognise and apply simple mathematical concepts to solving problems in everyday life. It includes basic skills such as addition and multiplication, which enable us to handle common functional maths topics such as weighing ingredients and telling the time. In contrast, the more complex domains of mathematics – such as algebra, trigonometry, calculus or topology – are a minority interest and most people leave them behind in the classroom.

However, mathematical reasoning provides a way to develop the mind and train the thought processes needed for problem solving. It is these basic skills that transfer to real-world problems. Some of the topics learned in the maths classroom may seem irrelevant, but it is important that we develop the analytical and logical thinking skills which will support future learning and comprehension.

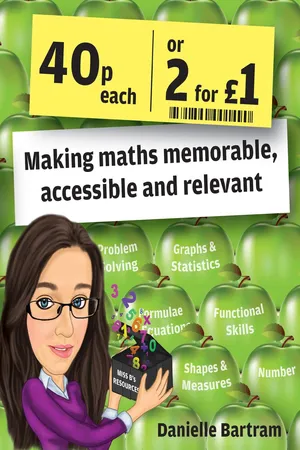

Figure 1.1 demonstrates how numeracy underpins the resources and principles in this book. In short, without the foundation of numeracy, students will be unable to understand or fully access the world around them.

It's not okay to be innumerate

There is a social stigma attached to calling someone illiterate, but this does not apply to being called innumerate. This could be because the need for literacy is an essential everyday requirement. If you can’t read you will struggle to perform many tasks that others find easy. It soon becomes obvious to others that you can’t read because you can’t understand written information – for example, that key aspect of modern life, the ability to send and receive texts. Literacy, unlike numeracy, is a visible skill that students can observe everywhere they go from a very early age. Conversely, many numerical tasks are performed automatically, such as on cash-registers in shops and online payment systems, and this seems to remove the requirement for mathematical competence.

Numeracy is often a more hidden skill that lurks in the depths of daily tasks. Young children can get by without a basic level of numeracy, but as they grow older the need for competence in numbers becomes an essential part of getting a job and in taking on the responsibilities of a householder. Numeracy is no longer a hidden skill.

Herein lies the basic problem. Students can’t comprehend what is needed in the future if they don’t know what to expect. Just telling them isn’t good enough. They need a clear understanding of why they are being asked to do things, and for many hard-core students who refuse to admit a need for numeracy skills, seeing is believing. Unfortunately, many students only realise the purpose and need for basic numeracy skills too late.

It is therefore essential that, as teachers, we provide opportunities for students to understand why they are doing things and the benefits they will get from learning particular aspects of numeracy. Unlike GCSE mathematics, where students study many things that they will probably never use again afterwards, it is important to place the need for numeracy in context as an essential life skill before we begin to teach the specific techniques they need to acquire.

There are two types of numeracy issues with students. The first is with those who can’t be bothered to learn the skills because they can’t see the purpose of them. The second is a much more delicate situation. It concerns those who struggle with mathematics and who may even suffer from dyscalculia. These students may get a lot of support and encouragement, but unfortunately – given th...