![]()

1 COMPIÈGNE AND THE TABUTEAU FAMILY

It was in mid-September of 1951 that I saw the French city of Compiègne for the first time. The Tabuteaus had invited me to accompany them on their drive to visit his relatives, the Létoffés. To reach Compiègne from Paris one travels slightly northeast for about an hour. The route passes through well-cultivated plains bounded by the peaceful, poplar-lined Oise River. Modern concrete-block-and-glass apartment buildings soon announce the approach to the outskirts of the town. But on arriving in the center of Compiègne, one is immediately aware of the vestiges of its rich and colorful past. The Hôtel de Ville, an imposing late Gothic edifice, still dominates the central square. Its façade boasts a flamboyant alcove that shelters a statue of Louis XII on horseback. Directly facing the famous king, le père du peuple (father of the people), Joan of Arc, leaning forward from the confines of her imposing bronze monument, triumphantly holds aloft an unfurled flag. The earlier church of Saint-Jacques stands nearby, only steps away from the half-timbered houses that survive from the medieval era. For centuries Compiègne was a witness to significant events in French history. At present in the département of Oise, in Roman days the city was known by its Latin name of Compendium after the shortcut running through the area. During the Middle Ages, drapers and cloth merchants came from Belgium, Germany, and many regions of France to the famous mid-Lent fairs. In 1430, during the Hundred Years’ War between France and England, Joan of Arc was taken prisoner by the English in Compiègne. Louis XV met the fifteen-year-old Marie Antoinette in the royal château when she arrived in France in May 1770 to be married to the Dauphin, the future Louis XVI. During the period of the Revolution in 1794, sixteen nuns from Compiègne were arrested and sent to Paris, where they were condemned to death and executed by the guillotine. It was this incident that Poulenc commemorated in his opera Les Dialogues des Carmélites. A plaque near the entry of the elegant, recently restored Théâtre Impérial marks the tragic site of the Carmelite convent.

Tradition has it that in 1810, Napoleon I, while awaiting the arrival of his fiancée, the Austrian princess Marie-Louise, ordered a five-kilometer-long strip of the forest behind the château to be razed. According to the romantic story, he wished to please her by creating a vista resembling the one she knew at Schönbrünn in Vienna. Throughout the nineteenth century there were state visits to the château. Louis Philippe received the ambassador of the Shah of Persia in the palace. During the Second Empire in 1868 a visit by the Prince of Wales, later to become Edward VII of England, was an occasion for pomp and celebration.

By the time the railway arrived in 1847, the population of Compiègne had reached 8,895 persons. Under the reign of Louis-Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, the court took up residence at the palace in order to be near the forest of Compiègne, long a favorite spot for the royal hunting season. Those who visit the château today can still see reflections of this brilliant period in the elegant state rooms with their silken wall coverings, brocade drapes, and fine inlaid wood furniture. The last royal visit to Compiègne took place in 1901 when Czar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra of Russia, along with the president of the Republic of France, drove by the flag- and flower-garlanded buildings on their way to attend a grand review of troops.

During World War I Compiègne was occupied and bombarded by the Germans, and its citizens were forced to flee. It was in the forest of Compiègne, just a few kilometers northeast of the town, that the Armistice of November 11, 1918, was signed in Marshal Foch’s private railway car. Only two decades later, in 1940, again in the path of the advancing German army, the historic heart of the city suffered much destruction. On a sad day in June 1940, Hitler insisted on using the same railway coach as the site for signing the new “Armistice” between France and Germany. Finally, after the hardships of the war years, Compiègne was liberated by the Americans on September 1, 1944.

Our visit on that Sunday in 1951 took place at the home of Tabuteau’s nephew, François Létoffé. I enjoyed the Létoffé hospitality of a superb luncheon, followed by a visit to the château with its memories of two Napoleons. François was the son of Marcel Tabuteau’s older sister, Charlotte. Throughout the next forty years I made periodic visits to Compiègne. Each time François Létoffé shared some of his childhood memories and old photo albums with me. Thus I gradually learned something of the Tabuteau family history.

Marcel’s father, François Tabuteau, born on February 3, 1851, was a Gascon from the small town of Saint-André-de-Cubzac about twenty kilometers north of Bordeaux in the département of Gironde. He was the eldest of six children of Étienne Tabuteau Guérineau and his wife Jeanne Landreau. Throughout his life, François would always use both names, “Tabuteau Guérineau,” when signing any legal paper. Marcel Tabuteau had the two names engraved on his Premier Prix medal from the Paris Conservatory. Was it done to distinguish their family from other Tabuteaus? No one has ever given a reason, but Tabuteau once remarked that Guérineau was a “better” name.

François Tabuteau became a highly skilled clockmaker and jeweler. He had three brothers: Jean, also a clockmaker, who remained in Saint-André-de-Cubzac; André, a teacher; and Octave, a curé or parish priest. His two sisters were named Anna and Blanche. Anna married a M. Babin, and Blanche a M. Gautier. Of all these uncles and aunts, the only one I ever heard mentioned was the curé. It was in May 1955 after Tabuteau had retired and was living at his home, La Coustiéro, in the south of France. I happened to be there one day when they invited the curé from the nearby village of Le Brusc to come for lunch. After he left I heard Madame Tabuteau say almost jokingly, “After all, there was a curé in your family!” It was customary for good nineteenth-century French families to designate one of their members for the religious orders. Having a curé in the family also indicated a distinct level of education. According to François Létoffé, “l’oncle abbé,” as the family called him, was not the most pious priest. He rode a bicycle, played the flute, kept a little mechanical train on top of his piano, and was even seen attending a theater in Bordeaux. That his musical bent was matched by inventive talents is evidenced by a letter he wrote to the famous flutist Paul Taffanel in 1899. Giving his word as a priest as recommendation, Abbé Tabuteau offered to demonstrate his invention of rubber pads for the flute by redoing and returning one of Taffanel’s own instruments within eight days.1

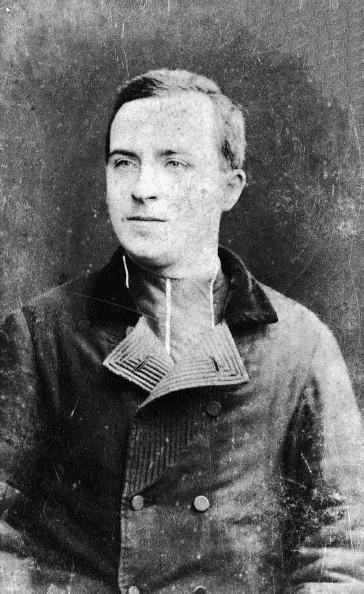

Tabuteau’s father, François Tabuteau-Guérineau, as a young man in velvet jacket about 1872. Photo by A. Guillerot, Compiègne

Before becoming established in the profession as an independent clockmaker, François Tabuteau had to make his “tour de France.” In the mid-nineteenth century the tour de France was far from the bicycle race known by that name today. Rather, it was a type of working trip undertaken by an artisan as one of the stages of apprenticeship in his field of expertise. He had to go from town to town with recommendations, staying in each place for several months or a year depending on the local needs. This was the way to qualify for the title compagnon (fellow workman; the completion of the time of service as a journeyman was known as compagnonnage) and was the equivalent of being accepted into a trade guild. But before receiving this title, the candidate was required to create a chef d’oeuvre in his chosen métier, which would then be examined by other compagnons in the same sphere of work. Tabuteau’s father fashioned a handsome clock that was to remain an object of importance in the family for many decades.

Octave Tabuteau (d. 1927), priest in Bordeaux. Known to the family as l’oncle abbé, he shows a definite resemblance to his nephew Marcel.

Tabuteau’s mother, Pauline Malaquin (1858–1945) at age nineteen or twenty.

It was while making his tour that François stopped in Compiègne and met Pauline Malaquin. Pauline was from the small town of Landrecy in the département du Nord, about a hundred kilometers from Compiègne, not far from the Belgian border. Her mother, Marie Julienne Grumiaux, born in 1837, was a marchande de marée (fishmonger) who married François Vital Malaquin, a tailor three years her senior. They had two daughters, Pauline Victorine, born February 28, 1858, and Aimée Julienne, born June 20, 1864. Marie Julienne had several brothers, all in working-class professions: Jules, a locksmith, and Alfred, a journeyman, born in 1849 and 1850, respectively. Another brother, Gustave, “uncle of the bride, a brewer age 42,” appeared as a witness at Aimée Julienne’s wedding in 1888, along with François Tabuteau, “brother-in-law of the wife.”2

François and Pauline’s wedding date has not survived in the family records, but on April 17, 1877, when he was twenty-six years old and she was nineteen, their first child, Pauline Charlotte (called Charlotte), was born. Three years later, in 1880, another daughter arrived, Esther Henriette (known as Germaine). Germaine, married at age seventeen to Camille Auxenfans, died in 1916 during World War I. The couple’s little daughter, Suzanne, is seen in some early family photos.

In 1887 the handwritten records in the Compiègne city hall give the following information under entry No. 316:

Tabuteau Guérineau, Marcel Paul

The year 1887 on July 4 at 11 o’clock in the morning. Before us, Alphonse Désiré Chovet, mayor and officier de l’État civil of the city of Compiègne, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, there appeared at the City Hall, François Tabuteau Guérineau, age 36, a clockmaker residing in Compiègne, presenting a male infant born the day before yesterday, July 2, at 7 o’clock in the evening at his home, 8 rue Magenta, to him and to Pauline Victorine Malaquin, his wife age 29 years, without profession, residing at the same address, and declaring his wish to name the baby Marcel Paul. This presentation and declaration was made in the presence of Victor Dufour, age 47, a carriage-builder, and Léopold Leseur, age 47, a wheelwright, both residing in Compiègne, who after reading the document have all signed it.

With the birth of another boy, André, on May 5, 1889, the Tabuteau family was complete. From the professions listed by the witnesses who signed the birth records of the four children, it is evident that the Tabuteau milieu consisted largely of Compiègne’s manual laborers, craftsmen, and artisans. A new influence came into the Tabuteau family with the marriage of Marcel’s seventeen-year-old sister Charlotte to Émile Létoffé, a well-trained violinist over twenty years her senior. Their wedding in Compiègne on September 4, 1894, was followed by a festive dinner at the Hôtel de L’Enfer.

Émile Létoffé would affect everyone in the Tabuteau family, but his impact on the life of his young brother-in-law (Marcel was only seven years old while his new relative was thirty-eight) was to be particularly strong. Létoffé had received a prize in violin in 1882 and was said to have studied with Dancla.3 He owned several good violins, including a J. B. Vuillaume and a Nicolas Amati ainé. As a result of trouble with his eyes he had an operation that obliged him to give up playing for a time. Later on he continued to teach violin in his home, always having difficulty finding the glasses he needed. He wanted everyone in the family to play a string instrument, but insisted that first they must study the solfège vocal system. His wife Charlotte played violin, their daughter Thérèse, the cello; both Marcel and his brother André studied violin. In 1896, with the formation of the Harmonie Municipale, which replaced the earlier Harmonie Jeanne d’Arc (a group of young musicians known as the Enfants de Compiègne), more wind players were needed. Marcel was drafted to play the oboe, and André, the clarinet. In the same band their father played the grosse caisse (bass drum). Decades later, the two brothers still remembered the time father François missed a cue from the band leader and came crashing in at the wrong moment. In the mid-1950s I heard Marcel and André tell the story. Reminiscing about their father and the grosse caisse still made them roar with laughter.

Marcel playing the violin; André, clarinet, and their niece Thérèse, mandolin, in 1898.

According to local census records for the ye...