- 640 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A comprehensive study of the Late Cretaceous, duck-billed dinosaur, featuring insights on its origins, anatomy, and more.

Hadrosaurs—also known as duck-billed dinosaurs—are abundant in the fossil record. With their unique complex jaws and teeth perfectly suited to shred and chew plants, they flourished on Earth in remarkable diversity during the Late Cretaceous. So ubiquitous are their remains that we have learned more about dinosaurian paleobiology and paleoecology from hadrosaurs than we have from any other group. In recent years, hadrosaurs have been in the spotlight. Researchers around the world have been studying new specimens and new taxa seeking to expand and clarify our knowledge of these marvelous beasts. This volume presents the results of an international symposium on hadrosaurs, sponsored by the Royal Tyrrell Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum, where scientists and students gathered to share their research and their passion for duck-billed dinosaurs. A uniquely comprehensive treatment of hadrosaurs, the book encompasses not only the well-known hadrosaurids proper, but also Hadrosaouroidea, allowing the former group to be evaluated in a broader perspective. The 36 chapters are divided into six sections—an overview, new insights into hadrosaur origins, hadrosaurid anatomy and variation, biogeography and biostratigraphy, function and growth, and preservation, tracks, and traces—followed by an afterword by Jack Horner.

"Well designed, handsome and fantastically well edited (credit there to Patricia Ralrick), congratulations are deserved to the editors for pulling together a vast amount of content, and doing it well. The book contains a huge quantity of information on these dinosaurs." —Darren Naish, co-author of Tetrapod Zoology, Scientific American

"Hadrosaurs have not had the wide publicity of their flesh-eating cousins, the theropods, but this remarkable dinosaur group offers unique opportunities to explore aspects of palaeobiology such as growth and sexual dimorphism. In a comprehensive collection of papers, all the hadrosaur experts of the world present their latest work, exploring topics as diverse as taxonomy and stratigraphy, locomotion and skin colour." —Michael Benton, University of Bristol

Hadrosaurs—also known as duck-billed dinosaurs—are abundant in the fossil record. With their unique complex jaws and teeth perfectly suited to shred and chew plants, they flourished on Earth in remarkable diversity during the Late Cretaceous. So ubiquitous are their remains that we have learned more about dinosaurian paleobiology and paleoecology from hadrosaurs than we have from any other group. In recent years, hadrosaurs have been in the spotlight. Researchers around the world have been studying new specimens and new taxa seeking to expand and clarify our knowledge of these marvelous beasts. This volume presents the results of an international symposium on hadrosaurs, sponsored by the Royal Tyrrell Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum, where scientists and students gathered to share their research and their passion for duck-billed dinosaurs. A uniquely comprehensive treatment of hadrosaurs, the book encompasses not only the well-known hadrosaurids proper, but also Hadrosaouroidea, allowing the former group to be evaluated in a broader perspective. The 36 chapters are divided into six sections—an overview, new insights into hadrosaur origins, hadrosaurid anatomy and variation, biogeography and biostratigraphy, function and growth, and preservation, tracks, and traces—followed by an afterword by Jack Horner.

"Well designed, handsome and fantastically well edited (credit there to Patricia Ralrick), congratulations are deserved to the editors for pulling together a vast amount of content, and doing it well. The book contains a huge quantity of information on these dinosaurs." —Darren Naish, co-author of Tetrapod Zoology, Scientific American

"Hadrosaurs have not had the wide publicity of their flesh-eating cousins, the theropods, but this remarkable dinosaur group offers unique opportunities to explore aspects of palaeobiology such as growth and sexual dimorphism. In a comprehensive collection of papers, all the hadrosaur experts of the world present their latest work, exploring topics as diverse as taxonomy and stratigraphy, locomotion and skin colour." —Michael Benton, University of Bristol

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Overview

1

A History of the Study of Ornithopods: Where Have We Been? Where Are We Now? and Where Are We Going?

ABSTRACT

Where ornithopod studies have been and where they are going is fascinating. I try to provide answers for the history of the study of ornithopod dinosaurs by collecting bibliographic data from the second edition of The Dinosauria. The resulting publication curves were examined for 10 intrinsic factors, nearly all of which increase through the first decade of the twenty-first century. These measures are used to take stock of present-day ornithopod studies and, finally, to try to predict our future as ornithopod researchers in this historically contingent world.

INTRODUCTION

From a historical perspective, knowledge about a taxonomic group can be judged by its publication rate. A zero rate may indicate a momentarily stalled interest in the group or a cessation of interest in it altogether (e.g., Kalodontidae Nopcsa, 1901), while a low rate suggests less than vigorous or meager research activity focused on the group (say, during a war or when there are few publishing scientists). Finally, a high publication rate may have many reasons, including new discoveries and new taxonomic recognition, and evolutionary controversy, to name a few.

Compilations of taxa are not new to studies of dinosaurs, or even tetrapods or invertebrates (Sepkoski et al., 1981; Benton, 1985, 1998; Dodson, 1990; Weishampel, 1996; Sepkoski, 2002; Fastovsky et al., 2004; Wang and Dodson, 2004). However, this present compilation and survey differs from previous varieties in that it focuses on the number of papers published and the research areas those papers address.

For Ornithopoda – the most abundant and diverse of which are hadrosaurids – the record of publication begins in 1825 with the publication of Mantell’s Iguanodon, and finishes with the numerous papers, some being issued via conventional journals as well as online-only journals, with no hard copies, of the present day. What this record looks like is presented in Figure 1.1. How it was obtained and how it is interpreted are the subjects of this chapter.

Caveat: although this volume is the product of a symposium dedicated predominantly to hadrosaurs, which includes hadrosaurids proper as well as hadrosauroids, it has been extended by the organizers to include iguanodontians as well. By stretching it slightly more to include iguanodontians, we are practically down to the base of Ornithopoda. Hence, this chapter is about hadrosaurs – and more.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In order to evaluate the rate of publication of papers dealing with ornithopod dinosaurs, the number of papers was tabulated on a per-decade basis from 1820–2010 from the bibliography of The Dinosauria, second edition (Weishampel et al., 2004). Containing 90 published pages of references on all dinosaurian taxa, this book is likely to be comprehensive enough for our current purposes. Because the decade of 2000–2010 was incomplete in that volume, the remainder of this decade was filled in proportionally based on the approximate representation during the first three and one-half years of the decade. That is, the 2000–2010 decadal numbers are projections based on tabulations from the first three and one-half years. Total papers and papers for each research category (see below) were adjusted by multiplying the raw totals for the first three and one-half years of the 2000–2010 decade by a factor of 2.86 to yield a total proportionally equivalent to other decades. This kind of correction was judged preferable to changing data sources (e.g., Web of Science), which would have resulted in an under-sampling of the more obscure literature.

In addition to the total curve, I have attempted to characterize the papers that went into this total by identifying nine categories of research (Table 1.1). I provide general description of these categories, denoted in boldface text, below. These categories were usually assessed by title alone, but occasionally it was necessary to consult the paper itself to determine to which category it belonged. I made no account of footprints and eggshell papers, because it was often impossible to assess affinities of the tracks or shell beyond Dinosauria from the title of the paper.

Table 1.1. Categories of Ornithopod Research Identified in This Survey

General taxonomy |

Functional morphology |

Phylogeny |

Biostratigraphy and taphonomy |

Biogeography |

Paleoecology |

Soft tissue |

Growth |

Faunistics |

General taxonomy refers to those publications announcing new specific or generic taxa, or new taxonomic revisions that do not come under the heading of phylogeny (see below). For example, Gilmore’s (1913) announcement of Thescelosaurus neglectus is here considered a work of general taxonomy.

Functional morphology is the category for papers involving a biomechanical or functional interpretation of an ornithopod anatomical system. An example of a functional morphology study is Alexander’s (1985) work on stance and gait in ornithopods among other dinosaurs.

Phylogeny refers to those studies that attempt to portray the evolutionary history, or phylogeny, of the group. In recent years, these studies have emphasized cladistics in phylogenetic reconstruction (e.g., Prieto-Márquez, 2010), but also include a number of pre-Hennigian analyses (e.g., Galton, 1972).

Biostratigraphy and taphonomy papers involve the geologic disposition of ornithopod specimens, whether within or among rock units. Rogers (1990) provided an example of how bonebed taphonomy can provide evidence for drought-related mortality in dinosaurs that include hadrosaurs.

Biogeography includes studies that examine the geographic distribution of ornithopods either from a dispersal or vicariant perspective, or both. For example, Casanovas et al. (1999) examined the global distribution of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids, whereas Upchurch et al. (2002) considered the full spectrum of controls on dinosaur diversity, including that of ornithopods, as a function of biogeography and biostratigraphy.

Paleoecology papers include those of Carrano et al. (1999) on convergence – or lack thereof – among ornithopods and ungulate mammals, and Varricchio and Horner (1993) on the significance of bonebeds in paleoecological interpretations, and are intended to address the reconstruction of particular taxonomically bound or free ecosystems of the past.

Soft tissue studies have been generally limited to skin impressions. Examples include Osborn (1912) on the “mummy” of Edmontosaurus annectens in the American Museum of Natural History.

Growth includes papers associated with aspects of ontogenetic development. The impact of growth on ornithopod studies is relatively recent. Here I note Dodson (1975) on the taxonomic significance of growth in Lambeosaurus and Corythosaurus, as well as various studies by Horner and colleagues (e.g., Horner et al., 1999, 2000) focused on the cellular basis of bone growth.

Faunistics includes papers whose principal purpose is to establish or review fossil assemblages that include ornithopods. For example, Lapparent (1960) reviewed the dinosaurs, including many ornithopods, from the “Continental intercalaire” of northern Africa.

Usually contributions were entered once in a category. However, a study can contribute here to several categories. For instance, Ostrom (1961) included discussion of general taxonomy, functional morphology, phylogeny, and other subjects in his major review of North American hadrosaurs, and so it was added to each of these categories.

WHERE HAVE WE BEEN?

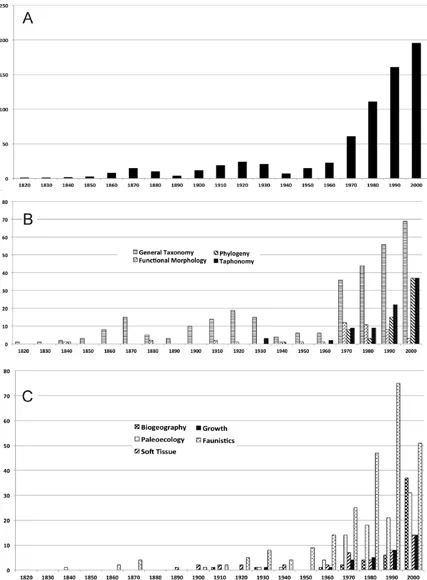

Where we have been can be determined by looking at the total curve of ornithopod publications (Fig. 1.1A). Beginning in the 1820s, the number of papers published per decade rises to a high of 15 in the 1870s. It then declines to 4 in the 1890s, and increases again, to 24, in the 1920s. The 1940s see a drop to 7, followed by a persistent, long-term increase to the decade of the 2000s, which is characterized by nearly 200 papers, amounting to almost 2 papers per month!

Before turning to several intrinsic factors, I want to examine three kinds of extrinsic events that may have influenced these numbers and patterns. For possible influences due to world events, the European revolutions of 1848, the American Civil War, World War I, the Russian Revolution, the fall of communism, and the combined Iraq and Afghan wars appear to have no substantial influence on rate of publication, whereas the 1929 stock market crash and the subsequent worldwide financial depression followed by World War II are likely factors in the decline of publication rates in the 1930s and 1940s. Regarding technological influences, there are no great fluctuations in rate of publication for technological events, except for the last two events. It is probably safe to say that the invention of personal computers, particularly laptops (1970s), in combination with the development of the World Wide Web and internet (1990s) made a huge impact on the rate of ornithopod publications. With the initiation of web publishing, this trend is certain to continue. Finally, scientific influences probably account for smaller perturbations in the total curve. For example, the discovery of the Iguanodon assemblage from Bernissart probably accounts for the rise in ornithopod publications during the 1870s and 1880s. The rise in publication rates during the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s can certainly be attributed to the Great Canadian Dinosaur Rush in Alberta. Finally, as a personal homage, I consider John H. Ostrom’s first monographic publication – his 1961 treatment of the hadrosaurids of North America – to signal the beginning of what has turned out to be a plethora of ornithopod publications to the present day.

1.1. Publication trends on ornithopod dinosaurs. (A) Total publication record of ornithopod dinosaurs from 1820 to 2000 tabulated by decade; (B) Total publications of general taxonomy, functional morphology, phylogeny, and biostratigraphy and taphonomy, tabulated by decade; (C) Total publications in biogeography, paleoecology, soft tissue, growth, and faunistics, tabulated by decade.

Intrinsic factors, on the other hand, are some of the subjects that I am interested in, which also have given Ornithopoda pride of place in the world of dinosaur publishing. General taxonomy and faunistics are the largest contributors to the total sample, whereas the rest have relatively low influence.

General taxonomy (Fig. 1.1B) has as long a history, beginning with the first publication on Iguanodon by Mantell (1825) and early on encompassing the first publication on Hadrosaurus by Leidy (1858). Furthermore, it mirrors fairly well the total publication curve, with a high point of 69 publications during the decade of 2000–2010.

Functional morphology (Fig. 1.1B) has a long, but patchy history, beginning with the publication of Mantell (1848) on the teeth and jaws of Iguanodon. It has never been common, but increases significantly in the 1970s and 1980s, with renewed interest in ornithopod jaw mechanics. Functional morphology has been in decline since this time.

Phylogeny (Fig. 1.1B) also has a long and equally patchy history, beginning with Owen’s (1842) christening of Dinosauria. Thereafter, there is a long hiatus until the 1970s, when we see an irregular publication record reflecting the large impact of cladistics on phylogeny estimates. The 1990s and 2000s indicate an important increase in cladistic studies, peaking near 40 publications.

Biostratigraphy and taph...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Reviewers

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1. Overview

- Part 2. New Insights into Hadrosaur Origins

- Part 3. Hadrosaurid Anatomy and Variation

- Part 4. Biogeography and Biostratigraphy

- Part 5. Function and Growth

- Part 6. Preservation, Tracks, and Traces

- Afterword

- Subject Index

- Locality Index (by country)

- Stratigraphy Index (by country)

- Taxonomic Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hadrosaurs by David A. Eberth, David C. Evans, David A. Eberth,David C. Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Natural History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.