![]()

II

OSCAR MICHEAUX

![]()

5.

Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates: The Possibilities for Alternative Visions

MICHELE WALLACE

Within the closed world they create, stereotypes can be studied as an idealized definition of the different. The closed world of language, a system of references which creates the illusion of completeness and wholeness, carries and is carried by the need to stereotype.

—Sander Gilman, Difference and Pathology1

The role of stereotypes is to make visible the invisible, so that there is no danger of it creeping up on us unawares; and to make fast, firm and separate what is in reality fluid and much closer to the norm than the dominant value system cares to admit.

—Richard Dyer, The Matter of Images2

The most prominent conceptions of black stereotypes in cinema studies, as conceived by Donald Bogle and Thomas Cripps, define such representations too narrowly—as harmful, reductive, and denigrating.3 Even recent endeavors to revise old approaches, for instance that of Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, do not quite succeed in addressing some of the most problematic issues. Rather, their emphasis is on devaluing stereotype analysis generally as an outmoded and not sufficiently subtle “negative/positive images” criticism.4 If we are to avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater, we need to follow the deconstructive work of Sander Gilman, Eve Sedgwick, and Richard Dyer and reconceptualize stereotypes or “types” as something of greater importance, ambiguity, and theoretical sophistication.5 Otherwise, distinguishing aesthetic achievement from the presumably deadening influence of stereotypes becomes all but impossible.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to explain the importance of Oscar Micheaux’s project in the silent film Within Our Gates (1920) without considerable reorientation with regard to stereotypes. To the uninitiated eye, this film might first appear to be a rather inept, unshapely attempt to imitate in blackface the entertainment values of early American film. From this perspective, a few lame swipes at lynching and white racism might appear to be hopelessly upstaged by a seemingly endless visual fascination with the goodness and beauty of light-skinned, bourgeois blacks.

Of course, I have no way of seeing inside of Micheaux’s mind (or the mind of any artist living or dead), nor is it my goal to unearth Micheaux’s original intentions at this late date. Yet it is possible to retrieve some relevant characteristics of Micheaux’s historical context in order to illuminate the relationship of his work to cultural ambivalences regarding race, gender, and sexuality of that time and so bring greater clarity to the contribution of a notable minority cultural practitioner. By so doing, I hope we will come to understand unimagined aspects of Micheaux’s oeuvre. Micheaux’s Within Our Gates focuses on race, very possibly in response to D. W. Griffith’s assault on the race in the hugely successful The Birth of a Nation (1915). In order to understand more precisely what Micheaux had to say about race, we will progress from a redefinition of stereotypes to a particular reading of black stereotypes in Griffith’s Birth as they impacted on Micheaux’s Within Our Gates.

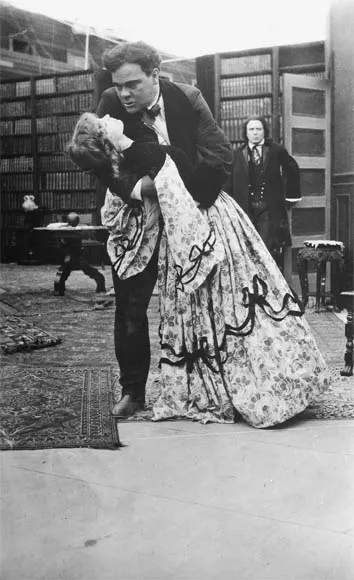

The Birth of a Nation (1915). Rehearsing the scene in which Silas Lynch (George Siegmann in blackface) tries to force Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) to marry him. Actor Ralph Lewis, playing Austin Stoneman, looks on.

According to Donald Bogle, the best known of contemporary black film historians, black stereotypes in cinema were originally codified in the Edison film version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1903). They subsequently changed very little until the blaxploitation films of the 1960s and 1970s when the “black buck” stereotype was allowed to make his first convincing appearance as the heroic, hypersexual black stud in such films as Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Shaft (1972), and Superfly (1972).6 The black buck first emerged as Gus in The Birth of a Nation (1915), Bogle says, but was judged too threatening, even in blackface, for southern audiences.

About his short list of stereotypes, which doubles for the title of his book Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films, Bogle says, “All were merely filmic reproductions of black stereotypes that had existed since the days of slavery and were already popularized in American life and arts.”7 Mostly uninterested in any kind of theorization or historicization of stereotypes, Bogle credits individual black actors and performers with endowing these lifeless figures with unanticipated dignity and range. Or, as he writes, “Often it seemed as if the mark of the actor was the manner in which he individualized the mythic type or towered above it.”8

Cripps, Shohat, and Stam, as well as numerous other commentators who focus primarily on contemporary film, seem to accept Bogles’s history of race representation in American film, and his breakdown and classification of stereotypes, without question. But the more I look at the films supposedly described by these categories of stereotypes, the more inadequate I find the categories to be.

To call a character a stereotype has long been a way of dismissing the character, the actor who played it, and often the entire picture. Indeed, I suspect this is why little is said in a critical mode about the so-called stereotypical black characters who occupy the background in many otherwise much-discussed films. There isn’t anything to say about a stereotype, is there? It has all been said. Stereotypes are supposed to die a quick and natural death of their own superficiality and dullness.

To what conclusion should we come if we really believe, as Bogle suggests, that five character types—four of them invented by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the fifth invented by Griffith in Birth (the brutal buck)—have continued to multiply and thrive across the spectrum of American popular culture for over 100 years? It should be clear, it seems to me, that these stereotypes must have considerable adaptive powers.

I would also argue that they and other more contemporary stereotypes and figures provide a sensitive historical template of the status of issues of gender and sexuality as well as race. To consider the ramifications of race in their construction without also taking into account gender, sexuality, class, and anything else of a historically specific nature seems to me pointless, especially since alternative constructions of gender, sexuality, and class are inextricably present in the formulation of the “difference” of “race.” Indeed, even as they simplify reality, these stereotypes have also assumed the weight of myth, which mystifies and unnecessarily complicates reality. And the problem with disposing of a myth is that people are often a great deal more attached to it than they realize.

Sander Gilman proposes, correctly, I think, that stereotypes of race, sexuality, and pathology or illness (physical and/or mental) are inextricably connected. I have come to share his psychological view that racism, misogyny, and homophobia are attempts to externalize inner conflict, self-hatred, fragmentation, and incoherence—all psychological mechanisms inevitable to human existence. As Gilman writes,

Order and control are the antithesis of “pathology.” “Pathology” is disorder and the loss of control, the giving over of the self to the forces that lie beyond the self. It is because these forces actually lie within and are projected outside the self that the different is so readily defined as the pathological.9

Given the worst-case scenario, when such inner turmoil coincides with onerous economic exigencies (as was the case in Weimar Germany and the postbellum South), then the result is liable to be genocide and/or protracted collective sadism aimed at the externalized “Other.” At such times, the object of hatred becomes a shifting, expanding and, in some ways, arbitrary one.

As Eve Sedgwick points out, difference will always be found everywhere one looks for it.10 As long as one persists in pining for a lost homogeneity and social cohesion, the situation can only deteriorate. Also, since such relatively blunt categories as race, sexuality, gender, and class can hardly begin to accommodate the range of possible differences of personality or their conceivable historical permutations, the more one enforces social homogeneity, the more problematic and potentially explosive difference becomes.

In the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American context, propelled by constant outbursts against blacks in the form of lynchings and race riots, the flames of hatred were also directed at immigrants, Asians, Jews, and Native Americans.11 This synergistic incubation of fear and loathing was both deliberate and conscious on the part of some hatemongers and, at the same time, as Shohat and Stam have pointed out, internalized and structural.

Yet, cultural expressions and symbolizations of this contempt for “difference” within the arts or popular culture signals the possibility of negotiation and intervention, precisely because symbolizations also intersect with the realm of the unconscious. I realize that this view of cultural expression as capable of positive intervention is not popular. Current practices of cultural criticism constantly incite us to see the representation and the reality as interchangeable, although they are often far from it. As Richard Dyer reminds us, “what is represented in representation is not directly reality itself but other representations,” and “cultural forms do not have single determinate meanings—people make sense of them in different ways, according to the cultural (including sub-cultural) codes available to them.”12

There is a lesson to be learned, for instance, from the saga of the way in which blackface minstrelsy, despite its portrayal of blacks as alien, non-sensical animals/children, has impacted on still-emerging forms of black representation in theatre, dance, the visual arts, and film. How white audiences progressed from the enjoyment of the Christy Minstrels in blackface to the enjoyment of “the real thing” of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, ragtime, and Bessie Smith—to the enjoyment of black musical theatre, Pigmeat Markham, Moms Mabley, and Richard Pryor—is no sugarcoated fairy tale.13 But life has never been a picnic for an impoverished ethnic minority within the heart of an overprivileged nation flexing its muscles.

In my view, the attempt to find some other ground, far from the poisonous terrain of blackface minstrelsy, upon which to judge and evaluate the politics and aesthetics of black artists, performers, directors, and technicians is doomed from the outset. When we are inundated by visual representations generally thought to be profoundly negative, it becomes very difficult to tell negative from positive and not to succumb to viewing virtually all black images as negative. This process inclines toward regarding anything discernibly “black” and/or dark as negative. As Gilman puts it,

The “pathological” may appear as the pure, the unsullied; the sexually different as the apotheosis of beauty, the asexual or the androgynous; the racially different as highly attractive. In all of these cases the same process occurs. The loss of control is projected not onto the cause or mirror of this loss but onto the Other, who, unlike the self, can do no wrong, can never be out of control. Categories of difference are protean, but they appear as absolutes. They categorize the sense of the self, but establish an order—the illusion of order in the world.14

Moreover, blackface minstrelsy’s cast of characters, images, and narrative expectations easily shook loose from the formal structure of the conventional three-part minstrelsy show to widely influence performance practices across the board—in vaudeville, burlesque, tent shows, musical theatre, drama, and film.

I break the most prevalent influences of minstrelsy down into three categories for purposes of this essay. The first of these involves whites playing black characters in blackface, usually but not always for comedic effect in the silent film period. This may actually be a much richer category than it first appears because U.S. films frequently employed white stars to impersonate people of color in both dramatic and comedic contexts. In the case of Asians, Latin Americans, and Native Americans, lead actors were commonly cast as white in “redface” or “yellowface.” Then, visually authentic-looking Asians, Latins, and Native Americans are frequently used as background, a kind of human mise-en-scène, for crowd scenes and to establish veracity. One also finds this convention persistently employed in casting dramatic black leads as white actors in dark makeup, with real blacks providing background until the early sound period. This policy is particularly noticeable in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: black characters with lines of dialogue are played by whites in blackface or brownface, whereas the violent actions of the black mobs are generally carried out by phenotypically and obviously black actors. Indeed, Cripps reports that these black players were confined to segregated camps during the filming process.15 The pr...