- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

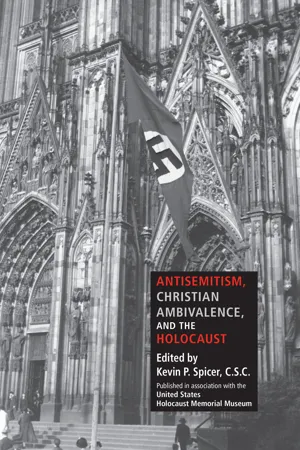

Antisemitism, Christian Ambivalence, and the Holocaust

About this book

Thirteen essays exploring the role of antisemitism in the political and intellectual life of Europe.

In recent years, the mask of tolerant, secular, multicultural Europe has been shattered by new forms of antisemitic crime. Though many of the perpetrators do not profess Christianity, antisemitism has flourished in Christian Europe. In this book, thirteen scholars of European history, Jewish studies, and Christian theology examine antisemitism's insidious role in Europe's intellectual and political life. The essays reveal that annihilative antisemitic thought was not limited to Germany, but could be found in the theology and liturgical practice of most of Europe's Christian churches. They dismantle the claim of a distinction between Christian anti-Judaism and neo-pagan antisemitism and show that, at the heart of Christianity, hatred for Jews overwhelmingly formed the milieu of twentieth-century Europe.

"This volume's inclusion of essays on several different Christian traditions, as well as the Jewish perspective on Christian antisemitism make it especially valuable for understanding varieties of Christian antisemitism and ultimately, the practice and consequences of exclusionary thinking in general. In bringing a range of theological and historical perspectives to bear on the question of Christian and Nazi antisemitism, the book broadens our view on the question, and is of great value to historians and theologians alike." —Maria Mazzenga, Catholic University of America, H-Catholic, February 2009

"Sheds light on and offers steps to overcome the locked-in conflict between Jews and Christians along the antisemitic path from Calvary to Auschwitz and beyond." —Zev Garber, Los Angeles Valley College and American Jewish University, Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1 Fall 2008

In recent years, the mask of tolerant, secular, multicultural Europe has been shattered by new forms of antisemitic crime. Though many of the perpetrators do not profess Christianity, antisemitism has flourished in Christian Europe. In this book, thirteen scholars of European history, Jewish studies, and Christian theology examine antisemitism's insidious role in Europe's intellectual and political life. The essays reveal that annihilative antisemitic thought was not limited to Germany, but could be found in the theology and liturgical practice of most of Europe's Christian churches. They dismantle the claim of a distinction between Christian anti-Judaism and neo-pagan antisemitism and show that, at the heart of Christianity, hatred for Jews overwhelmingly formed the milieu of twentieth-century Europe.

"This volume's inclusion of essays on several different Christian traditions, as well as the Jewish perspective on Christian antisemitism make it especially valuable for understanding varieties of Christian antisemitism and ultimately, the practice and consequences of exclusionary thinking in general. In bringing a range of theological and historical perspectives to bear on the question of Christian and Nazi antisemitism, the book broadens our view on the question, and is of great value to historians and theologians alike." —Maria Mazzenga, Catholic University of America, H-Catholic, February 2009

"Sheds light on and offers steps to overcome the locked-in conflict between Jews and Christians along the antisemitic path from Calvary to Auschwitz and beyond." —Zev Garber, Los Angeles Valley College and American Jewish University, Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1 Fall 2008

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Antisemitism, Christian Ambivalence, and the Holocaust by Kevin P. Spicer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Discrimination & Race Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Theological

Antisemitism

1 | Belated Heroism |

THE DANISH LUTHERAN CHURCH AND THE JEWS, 1918–1945

A Light in the Darkness?

Compared to most other countries, the Danish-Jewish experience seems to stand out as a remarkable exception in modern European history. Obviously, this perception is intrinsically linked to the unique rescue effort of the Danish people in October 1943, causing Nazi Germany’s attempt at rounding up and arresting Danish Jews to fail: only a few hundred Jews ended up being deported to Theresienstadt, and even of these, only about fifty—less than 1 percent of the more than seven thousand Jews living in Denmark at the time—perished.

One may date the origins of the positive image of Danish-Jewish relations back to the seventeenth century, when Glikl von Hameln, a merchant woman from Hamburg-Altona, praised the Danish king as just, pious, and extraordinarily benevolent toward Jews.1 The only dissertation on Danish-Jewish history published so far, Nathan Bamberger’s Viking Jews, traced this presumably exceptional phenomenon throughout Modern Danish history and concluded: “In the admirable history of Danish Jewry, one cannot overlook the Danes’ strong humanistic values, their sense of decency, and their care for all citizens.”2 Organizations such as “Thanks to Scandinavia” promote the Danish commitment to human dignity and ethical values in World War II as a role model for moral behavior today by stating: “The selfless and heroic effort of the Scandinavian people through the dark days of Nazi Terror is a shining example of humanity and hope for now and tomorrow.”3 In addition, books such as Moral Courage under Stress and The Test of a Democracy attest to this glorification of the Danish past in a Jewish perspective.4

Over the last two decades, in the collective memory of American Jews, Denmark has become the antithesis of a Nazi-dominated Europe bogged down by the collaborators’ active complicacy and the bystanders’ indifference. Despite this dominating perception of Denmark as a Righteous Nation—even honored as such by Yad Vashem—recent political developments suggest that it may be necessary to take a closer look at these positive portraits of Danish-Jewish relations. In 1999, the nationalist-conservative publishing house Tidehverv, run by Jesper Langballe and Søren Krarup, right-wing theologians and clerics, republished Martin Luther’s On the Jews and Their Lies. Langballe and Krarup are also both highly influential members of parliament for the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti), a populist radical right-wing party that constitutes the parliamentary basis of the present center-right government. In the introduction, the editors stress the work’s “contemporary relevance” in affirmative terms without any critical commentary, while employing anti-Jewish traditions to legitimize their xenophobic populist agenda. In light of the enduring positive image of Danish-Jewish history, this republication—and even more the fact that it did not provoke any academic protest, let alone public outcry—indicates that this perception deserves more scrutiny.

Recently, however, a series of newspaper articles that focused on Krarup and his anti-Jewish rhetoric sparked public criticism of these tendencies. Repeatedly, Krarup has attempted to exculpate Harald Nielsen, a writer who welcomed Nazi antisemitic legislation and favored the introduction of the Jewish star. Krarup has also sympathized with Nielsen’s attack on the Danish-Jewish literary scholar Georg Brandes by stating, “Because of his Jewish blood he felt no reverence towards or intimate connection with the country’s past.”5 Krarup reacted to allegations of antisemitism by emphasizing his rejection of racism and racial antisemitism as ideologies incommensurate with a Christian worldview. He also emphasized that his family had fought in the national-conservative resistance against the Nazi occupiers in Denmark. Through his reference to Christian convictions and nationalist orientations, Krarup positioned himself in line with key dimensions of Danish memory culture. To many observers, the most salient event in the history of the Jews of Denmark was their successful attempt to escape the Nazi roundup action of October 1943. As hundreds of non-Jewish Danes assisted them, this rescue operation over the Øresund added to the triumphalist narrative of successful integration that dominates the perception of Danish-Jewish history. This narrative, augmented by the sense of gratitude displayed by many Danish Jews for the rejection of antisemitism, has helped to view Danish Jews as the exceptional case of the European-Jewish experience. Danish Lutheran clergy played a key role in these rescue activities. Pastors warned Jews of the imminent danger of deportation, offered them hiding places, and facilitated their escape to Sweden. The pastor of Trinitatis Church in central Copenhagen even received the Torah scrolls from the nearby synagogue in Krystalgade and hid them in a secret chamber in his church. Even more explicit was the protest pastoral letter initiated by the bishop of Copenhagen, Hans Fuglsang-Damgaard, and signed on September 29, 1943, by all the Danish Lutheran Church bishops. It was an immediate reaction against the roundup of Danish Jews. On the following Sunday, October 3, 1943, Lutheran pastors throughout Denmark read the letter. Repeatedly, reports told of congregants rising from their pews to express their solidarity and support. The pastoral letter boldly stated that was the duty of the Lutheran Church to protest against the persecution of Jews because of Jesus’ own Jewish heritage and his command to love your neighbor. The letter also added an additional reason for protest:

Because [the persecution of Jews] conflict[s] with the understanding of justice rooted in the Danish people and settled through centuries in our Danish Christian culture. Accordingly, it is stated in our constitution that all Danish citizens have an equal right and responsibility towards the law, and they have freedom of religion, and a right to worship God in accordance with their vocation and conscience and so that race or religion can never in itself become the cause of deprivation of anybody’s rights, freedom, or property. Irrespective of diverging religious opinions we shall fight for the right of our Jewish brothers and sisters to keep the freedom that we ourselves value more highly than life. The leaders of the Danish Church have a clear understanding of our duty to be law-abiding citizens that do not unreasonably oppose those who execute authority over us, but at the same time we are in our conscience bound to uphold justice and protest against any violation; consequently we shall, if occasion should arise, plainly acknowledge our obligation to obey God more than man.

This unequivocal declaration of solidarity with Denmark’s Jews seems to confirm the exceptional status of Danish-Jewish relations. Nevertheless, the case of Krarup alerts us to the fact that the picture is more complex than this episcopal statement indicates. The work of Benjamin Balslev offers a starting point for an investigation of these ambiguities of Christian and clerical thinking about Jews.

The Ambiguities of the Christian Danish Perspective on Jews and Judaism

Benjamin Balslev was pastor at the parish of Soderup, an activist of Mission to Israel (Israelsmissionen), an organization committed to converting Jews, and the author of one of the early popular works on the history of Danish Jewry, The History of Danish Jews, published in 1932 in Copenhagen. In 1934, Balslev published an article on the “Race-Struggle in Germany” in the theological journal Nordisk Missions-Tidsskrift. Also published separately in the same year, this publication to some degree justified the persecution of Jews. Reports of a Nazi rule of terror did not dissuade Balslev in his beliefs that he developed over the previous two decades. Rather, he argued that there was merely a struggle going on between two peoples: Germans and Jews. Jews, he wrote, had an enormous and destructive influence both morally and economically in Germany. Furthermore, Jews constituted the bulk of an ethnically indigestible anti-Germanism that the Nazis fought to neutralize: “Germany has taken notice of its Jews and its Jewish question to a degree which is unknown to us. . . . While countries such as England and, we could add, Denmark always have had a homogeneous population, Germany has internally suffered from an anti-Germanism, something ethnically indigestible, and among these ranks, Germany’s Jews were disproportionally well represented.”6 Such thinking led Balslev to argue that the burning of allegedly morally detrimental books was a meaningful act of self-defense.

While Balslev purported to have the main objective to refute racist antisemitism and to reject racial theories and generalizing accusations against all German Jews, he still presented the ongoing disenfranchisement and persecution of Jews as the battle between two peoples. In Balslev’s twisted worldview, one should refute racial antisemitism because it defied conversion, God’s solution to the Jewish question. Nevertheless, he held that antisemitic perceptions, attitudes, and practices were legitimate since they constituted Germans’ defense against the detrimental influence of Jews on the economy and culture. His argument would then hold true for Denmark if its population were not homogeneous and if its Jewish community were less assimilated and more significant in terms of size and influence. Balslev’s point of view implied that, under these circumstances, such a reaction would be meaningful and necessary. Thus, the dream of an ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation proved to be the crucial pitfall of both Danish history and present politics.

Sources and Historiography

In order to understand the historical underpinnings of Danish Lutheran clergy’s attitudes toward Jews, one must examine the history of Danish-Jewish relations. In turn, this will provide a basis for an analysis of the dream of a homogeneous nation as it played itself out in the context of Danish clerical discourses and practices from 1918 to 1945. The discussion of these problems is, in contrast to the case of Norway,7 hampered by the still sizeable lacunae of research in this field. This is even more true in regard to the period’s church history. Recent publications are of limited use since they idealize the rejection of antisemitism in regard to clerical attitudes toward Jews.8 Here, my focus will not be on individual theologians or specific organizations, but rather on the “public sphere” of the church in its declarations, pastoral letters, protests, and written works. Because of this approach of mine, a certain bias in favor of those pastors and scholars who made the church’s views heard in public is naturally unavoidable. A lack of sources makes it very difficult to draw any “representative” conclusions on attitudes toward Jews among rank-and-file laymen, be it church members or activists, let alone conclusions regarding the relevance of clerical attitudes for the rescue action itself.

Frequently, scholars, journalists, and other intellectuals have presented “October 1943” as proof of the irrelevance or even absence of anti-Jewish resentment in modern Danish society. Similar to the case of England, antisemitism is understood to be an essentially un-Danish phenomenon. The roots of this concept are manifold: Danes are supposedly carrying an innate immunity against Jew-hatred—an immunity that is defined either in an essentialist way, by pointing to the humane and tolerant national character of the Danish people, or in historical terms, by referring to a specifically smooth “Danish Path” into a democratic, pluralistic, modern society. Furthermore, dubbing antisemitism as an import—a German import—without autochthonous roots and traditions, helped to reinforce this notion of immunity.

Finally, reference is often made to the specific nature of the Jewish community in Denmark, its “invisibility,” caused by the small number of Jews and their high degree of acculturation and integration. The successful story of integration and the notion of innate tolerance has contributed to dramatic lacunae of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Love Thy Neighbor?

- I. Theological Antisemitism

- II. Christian Clergy and the Extreme Right Wing

- III. Postwar Jewish-Christian Encounters

- IV. Viewing Each Other

- List of Contributors

- Index