![]()

My life is for myself and not for spectacle. I much prefer that it be of a lower strain, so it be genuine and equal, than that it should be glittering and unsteady. . . . To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance”

CHAPTER 1

Twin Vows

I grew up in a small, exclusive neighborhood of impressive homes with magnolia-, jasmine-, and rose-filled gardens. The several families who had built these fine homes and gardens owned stock in the same companies, belonged to the same clubs, sent their children to the same schools, and attended the same church (institutions that were segregated in those days). The presumption that long and enduring friendships would blossom among the beneficiaries of this elite segment of society was in my case never justified.

In the decades between two world wars, children—especially young women—seldom disappointed parental expectations, however often they might have wished to bolt imposed boundaries. My long-suppressed rebellious spirit came close to volcanic eruption in Houston during 1936, my first year after college. Well-intentioned and loyal friends of my parents gave endless lunches, dinners, and dances, for I was considered a proper debutante in my Parisian haute couture wardrobe. Not so. I had done nothing to merit the attention of kind hosts. I saw myself as a wild, alien creature who had been forcefully herded down from her native habitat into a glittering show ring and ordered to go through prescribed paces. I searched in vain for some loose planks in my imaginary enclosure but found none.

Nor was there an acceptable exit from societal expectations after my engagement to Kenneth Dale Owen, the estimable man who would be my husband for sixty-one years. My future role as an active member of Houston society and a promoter of good causes cast its long shadow before me. My family background and education together with Kenneth’s own impeccable credentials would place me in a position of leadership in the energy and oil capital of the world. Would I take a bold leap over my enclosure, embarrass the people I loved, break my legs, and smash my foolish face in the doing? Happily, and I believe by the grace of God, I didn’t have to kick over the traces.

A way out of confining expectations presented itself shortly after my marriage in July 1941 and opened the way for a second marriage. From my perspective today, I firmly believe that every first marriage can be preserved if a cerebral and spiritual marriage follows. The rumblings of discontent in our hearts can lead either to strained relationships and divorces or to life-enhancing breakthroughs. It is unwise to expect happiness solely from another person. Other women have saved their marriages by taking a law degree, answering a call to the ministry, or cultivating an undeveloped talent. Had anyone predicted that a sleepy, dusty little Indiana town would be my threshold to a higher consciousness, I would not have believed it. But something did happen in that unlikely place to redirect my life.

That something began with a stopover in New Harmony one hot August day in 1941, three weeks after our wedding at Ste. Anne, my family’s summer place in Ontario. As we were driving from Canada to Texas, Kenneth wanted me to see the town of his birth before pushing on to Houston. I had, of course, consented but not with enthusiasm. I had heard about my husband’s illustrious ancestors and had read Frank Podmore’s life of Robert Owen with my father before I met Kenneth. Daddy admired Owen for his factory and child labor reforms and initiated similar social benefits and an employee stock ownership plan for the Humble Oil Company that he helped found. For me, the legacy of Robert Owen and his fellow passengers on “The Boatload of Knowledge” existed chiefly in history books and biographies.

Blaffer sisters “Titi” (Cecil), Jane, and Joyce.

Blaffer-Owen family photograph.

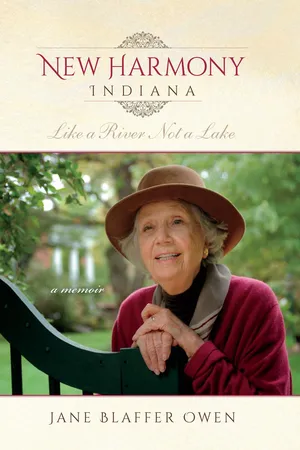

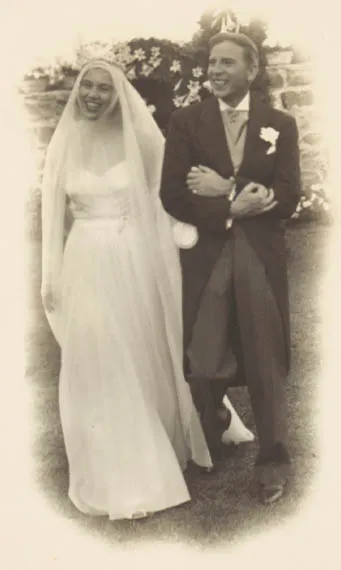

Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Dale Owen.

Blaffer-Owen family photograph.

Our car pulled up before an unusual house known as the David Dale Owen Laboratory, which I soon learned had been built in 1859 (4 on town map on back endpaper). David Dale Owen was a geologist.1 David’s elder brother Robert Dale, who was an early trustee of the Smithsonian, had chosen James Renwick Jr. as the architect for that institution, America’s first castle of science and first national museum.

David Dale had worked and taught in three laboratories before building this one: the Harmonist Community House No. 3 and the Harmonist shoe factory (both long gone from town), followed by seventeen years in the Harmonist stone Granary behind the Laboratory (5, 6, and 7 on town map, respectively). Successive generations of non-geologist Owens had converted David’s Laboratory into a family residence, and my husband called it home. I felt more like bowing my head than looking up because I was, in essence, bringing a wreath to the graves of noble men and women. But an alive and unforgettable presence was standing in the doorway to greet us: Kenneth’s elderly aunt Aline Owen Neal.

Auntie’s freshly laundered white cotton dress, full and floor-length, did not conceal or diminish her somewhat triangular shape. A black, curving ear trumpet emerged like a ram’s horn from the left side of her well-coiffed hair but was quickly lowered so both arms could embrace her nephew. Auntie didn’t grasp what we were saying, but no matter: sweetly smiling, she nodded assent to Kenneth’s every word. She had helped raise him. Ever since his first oil well, Kenneth had maintained her as the châtelaine of the Laboratory, a living monument to the Owen family.

I was no sooner inside than, like a stray cat, I wanted out. The twenty-foot-tall living room, designed to be a lecture hall with a gallery on three sides, was not hospitable. Several tables were stacked high with outdated newspapers and greeting cards. Auntie threw nothing away, perhaps because her nature was too gentle, her mind too comfortable in the past. As we hastened through the clutter to the circular dining room with its arched and diamond-hearted windows, I thought of the fairy tale that had captured my childhood imagination, where everyone, even the flies on the windowsills, had slept for a hundred years. In the story, a beautiful princess lay under an enchantment in a round tower. In the Laboratory, something as beautiful as a princess seemed to lie asleep, hidden from view, yet nonetheless palpably present. Could we summon enough love from our own hearts to awaken her and enough patience to recover her buried treasures?

The David Dale Owen Laboratory as it appeared on May 24, 1940, in the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS IND, 65-NEHAR, 1—2, Photograph by Lester Jones.

My husband brought me out of my reveries and unanswered questions. “It’s awfully hot in here, Jane. Let’s step outside,” he said, and held open the west door for me to enter an Old World courtyard, a square green space enclosed by a wall overhung with trumpet vines. A pair of gates had long ago opened for Owen carriages.

Beyond the north fence rose the sandstone and brick wall of the Granary, a massive structure that the German Harmonists had begun in 1814 and completed in 1822. Intended as a storehouse for food and grain, it could also serve as a fortress for protection. The Harmonists were avowed pacifists, so never a shot was fired from the tall, narrow slits of the ground floor. These openings were ventilators, not loopholes or meurtriers, the name of which was drawn from the French word for “murder.”

Turning back toward the Laboratory, I looked up in wonder at the conical witch’s-hat roof of the dining room and its weather vane. The directional markers—which would have pointed north, south, east, and west—were missing, but my eye lingered on a long, corkscrew-shaped column that supported a strange wooden fish. Time had battered its stomach and chewed its contours. Sensing my curiosity, Kenneth explained that the Paleozoic fossil fish had been great-uncle David’s tribute to the naturalist Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, one of the passengers on “The Boatload of Knowledge.” Lesueur had not only studied the anatomy of fish but, an accomplished artist, also drawn and painted them. I later learned that the supporting rod itself is an enlargement of both a blastoid, Pentremites, as the base and a bryozoan, Archimedes, a corkscrew-shaped fossil dear to the hearts of geologists and an apt colophon for a laboratory dedicated to science.

Kenneth’s blue eyes saddened as he ended his explanations. “We’ll have to find a good craftsman to replace this tired old fossil. Enough of this gloomy, run-down place,” he said. “I’ll take you across this mess of lawn to the white-pillared house on the far corner of the property that once belonged to us. The Lab is the only house in town still in my family.”

I remembered the same diffident look on Kenneth’s handsome face a few years earlier beside an entrance door of my own parents’ home. He had no idea I was watching through a window, fascinated by his gesture. Having rung the doorbell, he stepped back and with his right hand rubbed the signet ring on the little finger of his left hand. The ring was engraved with the double eagle that Hadrian’s Roman army had brought to New Lanark in the second century AD. Robert Owen had adopted this image for his own crest and, being egalitarian, placed identical eagles on the buttons of the coats of his employees. The intensity of Kenneth’s gesture seemed an unmistakable appeal to his ancestors for help in his pursuit of a difficult, pampered girl.

An appeal to ancestors for courage should come naturally from us, not only from a man in love. Many years later, words from Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust powerfully underscored my belief and spelled out the challenge given and taken by Kenneth. In a graveyard scene, a Gullah African American woman named Nana Peazant addresses her great-grandson Eli: “Those in this grave, like those who’re across the sea, they’re with us. They’re all the same. The ancestors and the womb are one. Call on your ancestors, Eli. Let them guide you. You need their strength. Eli, I need you to make the family strong again, like we used to be.”2

Through the window at my parents’ house, I saw a sensitive man appealing for guidance from earlier Owens and a never-to-be-underestimated mother. At the time, I could not yet appreciate the burden an alcoholic father places on a son’s shoulders. Witnessing his appeal achieved what the daily arrival of a dozen pink roses and at Christmas a pair of antique Italian armchairs had failed to accomplish. At last, after two years of indifference to Kenneth’s courtship, my self-centered ego moved over to make room for love and understanding. My parents announced our engagement shortly after my f...