![]()

Part I

COMPOSERS

![]()

FRESCOBALDI

(1583–1643)

Girolamo Frescobaldi Italian organist and composer, is considered by some to be the first great master of organ composition. In the preface of a few of his works, he gives valuable clues to performance practices in his time. After concluding a statement about the necessity of overcoming technical difficulties through practice, he writes: “Should a player find it tedious to play a piece right through he may choose such sections as he pleases, provided only that he ends in the main key” Regarding tempos: “The opening passages should be played slowly so that what follows may appear more animated. The player should broaden the tempo at cadences....” On trills and expression: “If one hand has a trill, while the other plays a ‘passage,’ do not play note against note but play the trill rapidly and the other expressively.”

Introducing a lecture-recital on Bach in London, c. 1950, Wolff discusses the neglect of “old” composers and extols the genius of Frescobaldi in particular.

At the time when I was a child, the general music-loving public believed that great music, our music, began with Bach and Handel. All earlier masters were of merely historic interest. The names of Palestrina, Schütz, and Corelli were known, but not their works. Those of Frescobaldi, Vivaldi, Monteverdi, not to mention Josquin des Prés or William Byrd, were completely unknown even to the professional. It may have been different in England, and I would be anxious to know whether British audiences were as familiar with Byrd and Dowland then as they are now.

Anyway, at the time I am speaking of, around 1910 to 1925, it was frequently said that if Bach was the greatest of all composers it was because he was the first, the originator of it all. But in the meantime we have experienced a general rediscovery of old music and old instruments....

Our knowledge of old music has become so general that at last the former patronizing attitude of the average music lover toward the old masters has disappeared. The beauty of some of their works is enjoyed directly in our day, by which I mean not only by a mental comparison with Bach and Handel: “See how Schütz already anticipates Bach’s Passions,” and that sort of thing.

I have chosen a Toccata by Frescobaldi, not only because I consider it a great masterwork but also because Frescobaldi was the earliest of the masters who directly influenced Bach. We know for a fact that Bach knew and studied some of his works. Frescobaldi could be called the Franz Liszt of the 17th century. He was organist at St. Peter’s and his glamorous improvising was so famous that on solemn occasions many thousands of people assembled outside St. Peter’s to hear him play. At the same time, like Liszt, he was intellectual and experimental.

“Toccata,” in Frescobaldi’s oeuvre, means exactly what it later means in Buxtehude and Bach: a keyboard piece in different short sections following each other without a real pause and unconnected in meter and speed, the whole being held together by the use of a few basic motives. The only difference is that in Frescobaldi, the sections are much shorter and therefore convey an even more improvisational atmosphere. The basic motive, in this instance, is furnished by the very first beginning.

If you compare this work with Bach’s Toccatas or Phantasies, it will strike you how much more domesticated, tame, and regular they seem—although within Bach’s own oeuvre they constitute a particularly spontaneous type of composition....The reason, of course, is not to be found in any lack of imagination or courage on Bach’s side. Nobody was more daring than he and more imaginative. However, Bach could create only in the pursuit of a big musical idea, and every single trait had to be subordinated to this idea, which makes for concessions in the freedom of musical detail. His toccatas, free as they are in rhythm and meter, do not quite measure up to Frescobaldi’s diversity of patterns, which one might compare with the language of a poet who historically would stand just on the border line between the medieval and present-day language, using the old grammar and vocabulary in all their wealth alternately with modern simplified word endings, so that the reader of today finds himself at home yet enjoys the embellishments furnished by the older elements.

The toccata you are going to hear, and which was published in 1637, that is, 3 generations before Bach’s works in the same form, gives a beautiful sample of his art. To the glamour of the improvisational richness and inventiveness is added a deliberate fusion of different styles, old church modes and modern tonalities, strict counterpoint writing in dissonant intensity—some passages indeed almost sound as if Stravinsky had looked them over....The wealth of the texture is enriched by sharp contrasts between flowing passages in even notes, and sharp rhythms, often in complex juxtaposition of duple time and triple time—here, too, an older and a newer style seem to be fused and integrated. Since the piece does not use the pedal of the organ it can be played on the piano exactly the way the composer wrote it, except for the overtone effects through doubling. The tone-colors—which, of course, would be slightly different on the organ—completely bring out the atmosphere of the piece.

The toccata presented in [Ex. 1] (opening section) may or may not be the one to which Wolff referred, but it is a good candidate. Frescobaldi wrote scores of them; this one seemed to come closest to the description. The music may be approached in a free, expressive style, which seems compatible with some of Frescobaldi’s comments on performance practice.

![]()

BACH (1685–1750)

His Last Work

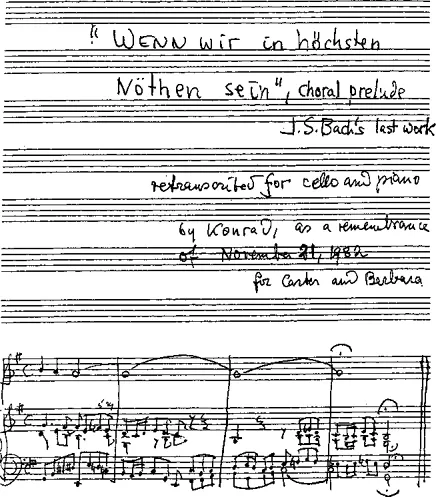

In 1982, Wolff transcribed Bach’s last choral-prelude for ’cello and piano as a gift for musician friends. He added a quotation on this work from Albert Schweitzer’s book J. S. Bach (chapter 12);5 Wolff’s comments follow. The final bars of the transcription have been combined with Wolff’s inscription by the editor (Ex. 2).

[Albert Schweitzer]

It seems that Bach spent his last days totally in a darkened room. When he felt that death was near he dictated to Altnikol6 a choral Fantasy on the melody “Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein” (when we are in ultimate crisis), but asked him to put as a title “Vor deinen Thron tret ich allhier” (here I step before Your throne), which is sung on the same tune. In the script one can still read all points of rest which the patient has to take. Day after day, the ink got more watery; the notes written in the half-dark behind darkened windows are hardly legible.

In the dark room, already surrounded by the shadows of death, the master created this work which, even among his own compositions, is unique. The counterpoint revealed therein is of such perfect art that no description could do it justice. Each segment of the hymn is treated in a fugue in which each time the inversion acts as a counter-subject. Nevertheless the voices flow so naturally that after the second line one is no longer aware of the métier, but is under the spell of the spirit which speaks to us in these G major harmonies. The noises of the world did not longer penetrate through the curtains of these windows. The dying master was surrounded by harmonies of the sphere. For this reason no suffering is included in the music. The quiet eighth-notes move beyond all human passion; over the whole piece there is the word “transfiguration” in lights.

[Konrad Wolff]

1982 is no longer as flowery as 1907 (the year of my birth and of the genesis of Schweitzer’s book), but I do feel very much along these lines, as far as the substance is concerned. The choral prelude is the ultimate condensation of his G major peace music—the Christmas oratorio; the two Preludes of the Well-Tempered Clavier books; the Fifth French Suite and the Fifth Partita in their Sarabandes; the Cello Suite, etc., etc. It is also the only piece known to me in which chromaticism appears in the major mode in Bach. The long last note of the hymn, under which all other voices die away, one by one, gently and serenely, is the closest one can come to describe Eternity in music, I think. So you see this scribbler, vintage 1907, is a little flowery himself still in 1982.

[Spirit, Style, and Forms: A Brief Exposition]

Extracted from a rough draft, this lecture-recital was the first of four given at St. Cecilia’s House in London for the benefit of the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund, year unknown but estimated to be about 1950.

His forms have often been compared to those of nature. There seems to be a natural order and coherence in the works which defy analysis, because the patterns are not totally regular nor calculable and include what G. K. Chesterton7 once called the “silent swerving from accuracy by an inch that is the uncanny element in everything.” Of the forty-eight fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier, for instance, there is not a single one without some irregularity, which one recognizes as such by looking at the other forty-seven fugues. Or take the Brandenburg Concertos. He establishes the type, in these six works, as a concerto in three movements, but the first concerto has four movements, and the third concerto only two. One might say that the only rule of form which he observes without exception is that in every piece there must be an exceptional occurrence proving the rule....

Bach is essentially a compose...