- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Tracing the expansion of South African business into other areas of Africa in the years after apartheid, Richard A. Schroeder explores why South Africans have not always made themselves welcome guests abroad. By looking at investments in Tanzania, a frontline state in the fight for liberation, Schroeder focuses on the encounter between white South Africans and Tanzanians and the cultural, social, and economic controversies that have emerged as South African firms assume control of local assets. Africa after Apartheid affords a penetrating look at the unexpected results of the expansion of African business opportunities following the demise of apartheid.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Africa after Apartheid by Richard A. Schroeder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Frontline Memories

One of the more perverse features of apartheid was the creation of black “homelands” or “bantustans.” These nominally autonomous territories were run by puppet governments and were expected to pursue independent development paths without assistance from Pretoria. Located on some of South Africa's most desolate wastelands, they were dumping grounds for displaced blacks who were forcibly evicted from areas that were coveted by whites elsewhere in the country (Butler et al. 1977).

The territory known as Bophuthatswana was perhaps the most infamous of the fictive homelands, in part because it contained the Sun City resort complex.1 Sun City, or “Sin City,” as the resort was known colloquially, traded on Bophuthatswana's quasi-independent status to offer forms of entertainment, such as gambling and topless female dancing, that were illegal in South Africa proper. It also afforded opportunities for South African audiences to witness performances by international musicians and other artists who were discouraged from performing in South Africa under the terms of the cultural boycott adopted by anti-apartheid campaigners in 1966.2 From the perspective of anti-apartheid activists, a performer's decision to “play Sun City” was tantamount to providing support for the apartheid system.3

The pretense of independent Bophuthatswana, and its use by performers to skirt the constraints of the cultural boycott, rankled many anti-apartheid campaigners. Performers affiliated with a group known as Artists United against Apartheid took it upon themselves to challenge the status quo. Led by Steven Van Zandt4 and including such notable musicians as Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Herbie Hancock, Bruce Springsteen, Pat Benatar, Ringo Starr, Ruben Blades, Run DMC, Lou Reed, Bonnie Raitt, Jimmy Cliff, Gil-Scott Heron, Joey Ramone, U2, and Keith Richards, this group produced a key anti-apartheid album entitled Sun City in 1985 (Marsh 1985). The title track contained a refrain voiced by each of the musicians: “I-I-I…ain't gonna play Sun City.” The song became the unofficial anthem of the international anti-apartheid solidarity movement in the United States and Europe (Thörn 2009, 434).

The Sun City project generated renewed interest in the cultural boycott and brought additional pressure to bear on those who sought to break it (Reed 2005, 165–72). It also yielded roughly a million dollars in profits, which organizers donated to the anti-apartheid cause. The primary recipients of Sun City largesse included the South African Council of Churches, which was led for many years by Nobel laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu; two of the leading U.S.-based anti-apartheid organizations, Transafrica and the American Committee on Africa (ACOA); and a seemingly obscure educational facility in rural Tanzania known as the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO).5 That an organization in Tanzania was singled out for such significant support at the height of the anti-apartheid struggle may seem surprising in retrospect. However, for the better part of three decades, Tanzania formed a crucial hub of political activity focused on the southern African liberation struggles. SOMAFCO itself hosted thousands of exiled South Africans under the auspices of the African National Congress from 1978 to 1992. Dozens of foreign delegations visited this “showpiece of the liberation struggle” in the 1970s and 1980s and subsequently contributed substantial sums to it (Morrow et al. 2004, 3; cf. Shubin and Traikova 2008, 1022; SADET 2008, vol. 3).

The prominence of SOMAFCO in the eyes of international anti-apartheid activists highlights the distinctive geography of the anti-apartheid struggle. A great deal of attention in the scholarly literature has been paid to the relative importance of “external” contributions by the international solidarity movement in comparison to the “internal” struggle being waged by combatants in South Africa itself.6 In this regard, Tanzania constituted neither an “external” nor an “internal” force, but instead occupied a third, interstitial space that remains relatively underexplored in histories of the period.7 Like Zambia, Botswana, and, later, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Angola, Tanzania was located on the “front line” of the region-wide struggles for southern African liberation. Its government provided refuge and respite to thousands of foreign nationals in exile even as it sought to secure its own borders and meet its obligations to fulfill the nation-building aspirations of its people.

SOMAFCO was in fact one of over a dozen Tanzanian sites that provided shelter for war refugees, served as military training bases, or hosted diplomatic conferences devoted to the liberation struggles. These installations provided Tanzanians in all corners of the country with opportunities to meet their “brothers and sisters” from the south and absorb the ethos of the liberation struggle through firsthand social contact. Tanzanians who came of age during this period recall with pride the central role their country played in the liberation struggle. As I show below, the political consciousness that emerged in Tanzania during this period has been long-lived. Indeed, it continues to shape Tanzanians' attitudes toward South Africans well after the formal end of apartheid in the early 1990s.

Regional Solidarity in “The Struggle”

For Tanzania, efforts to end white domination in southern Africa actually began in the late 1950s, and President Nyerere quickly became a leader of the international solidarity movement (Houser 1989; Minter 1994; SADET 2004, 2007, 2008; Khadiagala 2007). “The struggle,” as it was known in the political parlance of the time, moved forward on several fronts simultaneously. These included the anticolonial wars leading to independence in the former Portuguese colonies of Mozambique (1975) and Angola (1975); the ensuing civil wars in each of those countries against counterrevolutionary forces backed in part by South Africa (mid 1970s through 1990s); the overthrow of the white settler regime in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe (1980); the fight for independence in South Africa-occupied Namibia (1990); and the anti-apartheid campaign in South Africa itself culminating in the election of the ANC government in 1994. Though each of these national liberation movements had its own political character, as far as Nyerere was concerned, they were all ideologically linked. His position, which he shared with Nkrumah and other prominent African leaders and helped establish as a guiding principle of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), was quite clear: “We shall never be really free and secure while some parts of our continent are still enslaved.”8

Safe Haven

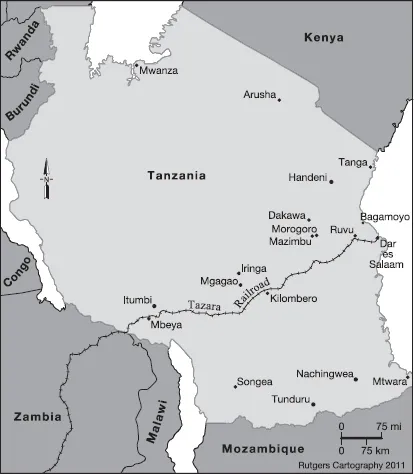

Tanzania's support for the liberation struggle ultimately took several forms. One of its earliest objectives was to provide humanitarian relief services to civilian groups fleeing war and political repression. When the army of the Mozambican liberation front (Frelimo) began attacking Portuguese colonial forces in northern Mozambique in 1964–65, and the Portuguese retaliated by burning dozens of Mozambican villages along the border, many of the displaced Mozambicans fled into Tanzania.9 By 1965, some 7,000 Mozambican nationals had taken refuge in Tanzania, and that number grew to an estimated 50,000 by the early 1970s as the war against the Portuguese colonial regime intensified (Chaulia 2003, 156). In order to meet the needs of this large refugee community, Nyerere's government allowed Frelimo to set up facilities offering a range of social services to Mozambican nationals, including a secondary school in Bagamoyo, a center for women and children in Tunduru, and a hospital serving war wounded in Mtwara (see map 1).10

The story was much the same with respect to South African refugees. When thousands of young South Africans fled their country in the wake of the apartheid regime's crackdown following the Soweto uprising of 1976, many found their way to Tanzania.11 The ANC's Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO)—the recipient of funds from the Sun City project—was subsequently opened on a sisal plantation provided by the Tanzanian government in the community of Mazimbu in Tanzania's Morogoro district in 1978.12 A second facility was later opened by the ANC in the nearby town of Dakawa. The two ANC camps eventually housed some 5,000 South African exiles and provided services to them via a secondary school, a primary school, a nursery, a farm, and a development skills training center. Their goal was to ensure that the exiles would be “practically and intellectually equipped to make their contribution [to] the struggle…and to take their rightful place as citizens in a free and democratic South Africa of the future” (Morrow et al. 2004, 15). They pursued this mission until 1992 when Nelson Mandela, newly freed from prison, paid a historic visit and called his countrymen and women back home again.13

The residents of these camps had extensive economic ties with surrounding communities: SOMAFCO hired a significant number of Tanzanians as farm laborers, its farm surpluses were sold in local markets, and traders from nearby communities bartered cigarettes with SOMAFCO students in exchange for clothing and other items sent through foreign aid channels (Morrow et al. 2004, 113–31). To facilitate communication, ANC members learned to speak Kiswahili, and Tanzanians in the area picked up South African dialects. South Africans also played in local sports leagues. Binational marriages were not uncommon. In these respects, the refugee and military encampments that dotted the Tanzanian landscape left a lasting impression on neighboring Tanzanian communities.

In addition to land for the camps themselves, the Tanzanian government and its citizens made a number of other contributions to the needs of the refugee groups. Early on, the government committed one percent of its national income to the Liberation Fund of the Organization of African Unity (Chaulia 2003, 155), and for a brief period, it paid some refugees a daily living allowance.14 The Tanzanian government helped stock Frelimo shops by exchanging everyday necessities for goods that were produced in the liberated zones of northern Mozambique.15 Ordinary Tanzanian citizens routinely donated clothing, blood, and money to support the exiled groups.16 Thus, for example, when Tanzania's ruling party, the Tanzania African National Union (TANU), declared 1974 the “year of liberation,” Tanzanians contributed a total of four million Tanzanian shillings (approx. $286,000) to assist Frelimo in its final push to free Mozambique from Portuguese rule (Kisanga 1981, 113).17

Military Involvement

Tanzania's proximity to the Mozambican battle lines made its direct military involvement in the struggle virtually inevitable. At the same time, its relative distance from the core of South African influence meant that its national territory was strategically significant as a training and staging area for nearly every set of freedom fighters active in the region:

It is a well-known fact that guerrilla fighting for the liberation of Rhodesia, Angola, Mozambique, and South West Africa has been able to occur largely because of the fact that there are bases for training of troops and launching of attacks in the neighboring Zambia, Tanzania and Congo. Were those three countries to discontinue their policy of harboring liberation movements, the struggle for freedom would virtually be rendered impossible.18

During the early years of the liberation struggle, Dar es Salaam was the terminus of an extensive underground railway that funneled exiled military personnel from all over the region into and through Tanzania for training (Ndlovu 2004, 454–60). Indeed, the Tanzanian countryside was dotted with military installations hosting foreign guerrilla armies. Frelimo established as many as ten different military bases and supply camps on Tanzanian soil, including its headquarters in Nachingwea. The battle for Namibian independence was launched directly from a military training camp in Kongwa in Tanzania's Dodoma district in 1966. South Africa's ANC had four different military camps in Tanzania (Kongwa, Mbeya, Bagamoyo, and Morogoro), and its rival, the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), had camps in Mbeya and Ruvu. Zimbabwean guerrilla forces were trained and staged at bases in Mgagao, Morogoro, and Itumbi (see map 1).19

These various groups of “freedom fighters” received instruction from Cuban, Russian, Algerian, and Chinese military trainers, among others, both on Tanzanian soil and abroad. They availed themselves of military supply chains that ran through Tanzanian ports—Chinese military funding and weapons supplies delivered via Tanzania, for example, had reached a level of over $40 million by 1972. And they took advantage of countless donations ostensibly contributed for “humanitarian” purposes to help support military personnel exiled within the country. Much of this funding was funneled through the OAU's Liberation Committee, but direct bilateral donations to the Tanzanian government were also often destined for redistribution in the liberation camps.20

Tanzanian civilians and military personnel were killed in Tanzania in repeated cross-border incursions by Portuguese colonial forces in the early 1970s. Thousands of Tanzanian troops also became directly involved in military action outside its borders, most notably to help defeat counterrevolutionary forces in Mozambique. Operation Safisha (“Cleanup”) launched in Mozambique in 1976 resulted in over a hundred Tanzanian casualties. Tanzanian soldiers also participated in military actions in Rhodesia.21 Additionally, Tanzania's police and army were deployed internally to help defend the liberation camps. The Tanzanian military helped protect the ANC, for example, which was in a state of perpetual alert against the prospect of an attack on SOMAFCO by South African security forces:

Map 1. Sites of solidarity in Tanzania. Over a dozen different Tanzanian communities supported the southern African liberation struggles by sheltering war refugees or hosting military training bases and diplomatic conferences.

MICHAEL SIEGEL, RUTGERS CARTOGRAPHY.

The sense of threat from the South African regime was also noticeable…[SOMAFCO] authorities continually emphasized that being outside South Africa did not mean that they were safe, and that vigilance was essential. In the early 1980s there were rumours that the regime was going to attack SOMAFCO, and that South African forces would use Malawi as a staging post to fly to Mazimbu. It was said that the official opening of the school in 1985 was to be targeted…As a result of such fears, trenches were dug all over the Mazimbu campus…In one incident, the water supply from the nearby Ngerengere River was poisoned. Luckily, local people noticed that fish were dying in the river, and they notified the SOMAFCO authorities.22

Map 2. Key frontline states. The four presidents of Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique, and Botswana led the Frontline States alliance in opposition to the “white, racist, imperialist regimes” to the south.

MICHAEL SIEGEL, RUTGERS CARTOGRAPHY.

Similar threats were directed at the Zimbabwean camps in Tanzania.23

On two separate occasions, prominent members of the liberation movements living in exile in Dar es Salaam were assassinated. The most sensational of these events was the killing in 1969 of Eduardo Mondlane, the president in exile of Frelimo, who died instantly when a parcel bomb sent by the Portuguese political police exploded as he opened it (Brittain 2006). The second incident involved PAC leader David Sibeko, who was killed by PAC comrades in 1979 (Kondlo 2008, 177–78). Tensions within the liberation movements also erupted when Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) forces attacked and killed “a considerable number” of Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) guerrillas at their joint military bases in Mgagao and Morogoro in 1976 (Martin and Johnson 1981, 243; Chung 2006, 315).

Strategic Infrastructure

Tanzania also provided strategic logistical support to its neighbors. Tanzania's most important ally in the region, Zambia, shared borders with Rhodesia, Mozambique, Angola, and Southwest Africa (Namibia), and was thus much more directly exposed to attack by anti-liberation forces than Tanzania. Zambia was also economically vulnerable because it was landlocked; its primary routes to port accounting for nearly all its imports and exports in the early 1960s ran through white-held Rhodesia, Angola, Mozambique, and South Africa (see analysis in Mwase 1987, 191–98; Griffiths 1969, 214; see also map 2). In 1965, this situation reached crisis proportions when Ian Smith's government in Rhodesia issued its “Universal Declaration of Independence” (UDI) from Britain and placed an embargo on oil deliveries to Zambia in retaliation for Zambia's support for Zimbabwean guerrilla groups.

To break the stranglehold on the Zambian economy and promote development within both Zambia and Tanzania, three parallel infrastructure projects were undertaken. Presidents Kaunda and Nyerere coordinated plans for the construction of an oil pipeline (TAZAMA) and a new rail line (TAZARA) (see map 1). Simultaneously, a highway connecting the two countries was built by an American construction firm.24 Of the three projects, the Italian-funded pipeline provided the first relief from the Rhodesian oil blockade (Griffiths 1969, 216), but it was TAZARA that arguably carried the greatest symbolic significance.25

Initially, Nyerere and Kaunda sought funding for TAZARA from western governments and multilateral donors.26 When these actors denied support to the project, the two presidents were forced to seek help from the Chinese government, which seized the opportunity to align itself with the liberation struggle and gain political capital at the western governments' expense:

The Chinese-sponsored TAZARA was known as the “Freedom Railway,” the critical link to the sea that landlocked Zambia desperately needed in order to break free from her dependency on Rhodesian, Angolan, and South African rails and ports. TAZARA was therefore also an anti-apartheid railway, a symbol of revolutionary solidarity and resistance to the forces of colonialism, neoco...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1. Frontline Memories

- 2. Invasion

- 3. Fault Lines

- 4. Tanzanite for Tanzanians

- 5. Bye, the Beloved Country

- 6. White Spots

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index