eBook - ePub

A Century of Ambivalence

The Jews of Russia and the Soviet Union, 1881 to the Present

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Illuminated by an extraordinary collection of photographs that vividly reflect the hopes, triumphs and agonies of Russian Jewish life." —David E. Fishman,

Hadassah Magazine

A century ago the Russian Empire contained the largest Jewish community in the world, numbering about five million people. Today, the Jewish population of the former Soviet Union has dwindled to half a million, but remains probably the world's third largest Jewish community. In the intervening century the Jews of that area have been at the center of some of the most dramatic events of modern history—two world wars, revolutions, pogroms, political liberation, repression, and the collapse of the USSR. They have gone through tumultuous upward and downward economic and social mobility and experienced great enthusiasms and profound disappointments.

In startling photographs from the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and with a lively and lucid narrative, A Century of Ambivalence traces the historical experience of Jews in Russia from a period of creativity and repression in the second half of the 19th century through the paradoxes posed by the post-Soviet era. This redesigned edition, which includes more than 200 photographs and two substantial new chapters on the fate of Jews and Judaism in the former Soviet Union, is ideal for general readers and classroom use.

Published in association with YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

"Anyone with even a passing interest in the history of Russian Jewry will want to own this splendid . . . book." — Los Angeles Times

"A lucid and reasonably objective popular history that expertly threads its way through the dizzying reversals of the Russian Jewish experience." — The Village Voice

A century ago the Russian Empire contained the largest Jewish community in the world, numbering about five million people. Today, the Jewish population of the former Soviet Union has dwindled to half a million, but remains probably the world's third largest Jewish community. In the intervening century the Jews of that area have been at the center of some of the most dramatic events of modern history—two world wars, revolutions, pogroms, political liberation, repression, and the collapse of the USSR. They have gone through tumultuous upward and downward economic and social mobility and experienced great enthusiasms and profound disappointments.

In startling photographs from the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and with a lively and lucid narrative, A Century of Ambivalence traces the historical experience of Jews in Russia from a period of creativity and repression in the second half of the 19th century through the paradoxes posed by the post-Soviet era. This redesigned edition, which includes more than 200 photographs and two substantial new chapters on the fate of Jews and Judaism in the former Soviet Union, is ideal for general readers and classroom use.

Published in association with YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

"Anyone with even a passing interest in the history of Russian Jewry will want to own this splendid . . . book." — Los Angeles Times

"A lucid and reasonably objective popular history that expertly threads its way through the dizzying reversals of the Russian Jewish experience." — The Village Voice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Century of Ambivalence by Zvi Gitelman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CREATIVITY VERSUS REPRESSION:

THE JEWS IN RUSSIA, 1881–1917

Early Sunday afternoon, March 1, 1881, Tsar Alexander II left his palace in St. Petersburg to review the maneuvers of a guards battalion. He was known as the “Tsar Liberator” because he had emancipated millions of serfs, reformed the legal and administrative systems, eased the burdens of military service, and allowed more intellectual freedom. Nevertheless the revolutionaries of the Narodnaia Volia (People’s Will) organization described him as the “embodiment of despotism, hypocritical, cowardly, bloodthirsty and all-corrupting. . . . The main usurper of the people’s sovereignty, the middle pillar of reaction, the chief perpetrator of judicial murders.” As long as he did not turn his power over to a freely elected constituent assembly, they pledged to conduct “war, implacable war to the last drop of our blood” against the sovereign and the system he headed.

Well aware of the danger to his life, the tsar usually varied his travel routes. On this cloudy day, as his carriage turned onto a quay along the Neva River, a young man in a fur cap suddenly loomed up in front of the royal entourage and threw what looked like a snowball between the horse’s legs. The bomb exploded but wounded the tsar only slightly. His Imperial Highness got out to express his solicitude for a Cossack and a butcher’s delivery boy who had been severely wounded. Turning back to his carriage, he saw a man with a parcel in his hand make a sudden movement toward him. The ensuing explosion wounded both the tsar and his assailant. Rushed to the Winter Palace, the tsar died within an hour. His assailant died that evening without revealing either his name or those of his Narodnaia Volia co-conspirators. But the man who threw the first bomb, a recent recruit to the revolutionary ranks, informed on his comrades to the police interrogators. The sole Jew among those comrades was Gesia Gelfman, a young woman who had run away from her traditional home to avoid a marriage her parents had arranged for her when she was sixteen. She was found guilty of conspiracy to murder the tsar, as were another woman and four men. All were sentenced to hang. Because Gelfman was pregnant, her sentence was commuted to life at hard labor. She died a few months after giving birth, possibly because of deliberate malpractice, and her infant died at about the same time.

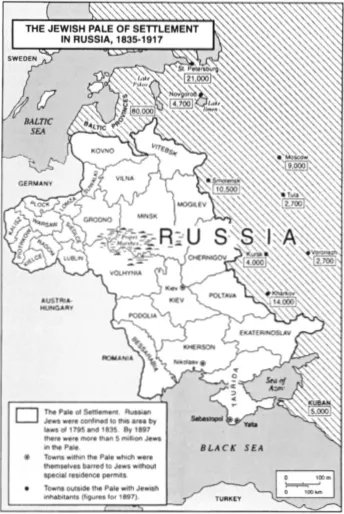

Soon after the assassination of Alexander II and the ascension to the throne of Alexander III, a wave of pogroms swept over Russia and the Ukraine as the word spread that the Jews had murdered the “Little Father” in St. Petersburg. A quarter century of relative tranquility and modest progress for the Jews had ended. Jews had entered the Russian Empire in large numbers only a century before, when the imperial appetite of the tsars led them, reluctantly, to swallow unwanted Jews along with the coveted territories of Poland divided among the Russian, Hapsburg, and German empires. The huge Jewish population of the Polish territories was taken in, though barred from moving elsewhere in the empire and confined to the “Pale of Settlement.” For about a hundred years thereafter they had experienced cycles of repression and relaxation. Sometimes the hand of the tsars would come down heavily on the Jews, while at other times it beckoned seductively and urged them to change their “foreign ways” and assimilate into the larger society. For nearly a century Russian society and its leadership had tried to change the Jews. Indeed, some of the Jews themselves preached a reform of Jewish ways so that they would be more acceptable to Russian society. But a few decades before the assassination of Alexander II, a handful of Jews began trying to change not only themselves but Russian society and its political system as well. During the century following 1881 the dialogue between Jews and their neighbors was to be laden with ambivalence and distrust, but also with great hope and idealistic aspirations.

Maria Grigorevna Viktorovich and her daughter, Esfir Aronovna, Tomsk, Siberia, 1914. Credit. Berta Rostinina

The husband of Maria Viktorovich, Aron Abramovich, merchant of the first guild, a status that allowed him to live outside the Pale of Settlement, St Petersburg, 1900 Credit: Berta Rostinina.

THE “IRON TSAR” AND THE JEWS

Nicholas I’s ascension to the imperial throne in 1825 marked the start of the most difficult period for Russia’s Jews. As the historian Michael Stanislawski has observed, “To Nicholas, the Jews were an anarchic, cowardly, parasitic people, damned perpetually because of their deicide and heresy; they were best dealt with by repression, persecution, and, if possible, conversion.”1 Through various decrees and restrictions, large numbers of Jews were displaced from their traditional occupations and places of residence during the thirty years of Nicholas’s rule. But the harshest decree was issued in 1827, when the tsar ordered that each Jewish community deliver up a quota of military recruits. Jews were to serve for twenty-five years in the military, beginning at age eighteen, but the draftable age was as low as twelve. Those under eighteen would serve in special units called Cantonist battalions until they reached eighteen, whereupon they would begin their regular quarter century of service. As if a term of army service of thirty years or more were not enough, strenuous efforts were made to convert the recruits to Russian Orthodoxy, contrary to the provisions of religious freedom in the conscription law. A double catastrophe fell on the heads of Russian Jewry: their sons would be taken away not only from their homes and families but in all likelihood also from their religion. Little wonder that all sorts of subterfuges were used in attempts to avoid military service. One can even understand the willingness of the wealthy, and of the communal officials whom they supported, to shield their own children from service by substituting others, as was allowed by law. The hapless substitutes were almost always the children of the poor and socially marginal. The decree fell upon them with especial cruelty, as they watched khapers (snatchers) employed by the community tear their children, no less beloved though they were poor, from their arms. The oath of allegiance was taken by the recruits who were dressed in talis and tfilin (prayer shawl and phylacteries) as they stood before the Holy Ark in the synagogue, and was concluded by a full range of shofar blasts. This only further embittered the recruits and their families, not only toward the tsarist regime but also toward the “establishment” of the Jewish community. A Yiddish folk song of the time expressed the sentiment poignantly:

Trern gisen zikh in di gasn

In kinderishe blut ken men zikh vashn. . . .

Kleyne eyfelekh rayst men fun kheyder

Me tut zey on yevonishe kleyder.

Undzere parneysim, undzere rabbonim

Helfn nokh optsugebn zey far yevonim

Ba(y) Zushe Rakover zaynen do zibn bonim,

Un fun zey nit eyner in yevonim.

Nor Leye di almones eyntsike kind

Iz a kapore far koholishe zind.

Tears flow in the streets

One can wash oneself in children’s blood. . . .

Little babies are wrested from school

And dressed up in non-Jewish clothes.

Our leaders and our rabbis

Even help turn them into Gentiles.

Rich Zushe Rakover has sevens sons

But not one puts on the uniform.

But Leah the widow’s only child

Has become a scapegoat for communal sin.

Alexander Herzen, one of the first ideologists of the Russian revolutionary movement, encountered a group of Jewish recruits in 1835 and described the scene as “one of the most awful sights I have ever seen.” “Pale, exhausted, with frightened faces, they stood in thick, clumsy, soldiers’ overcoats . . . fixing helpless, pitiful eyes on the garrison, soldiers who were roughly getting them into ranks. The white lips, the blue rings under their eyes bore witness to fever or chill. And these sick children, without care or kindness, exposed to the raw wind that blows unobstructed from the Arctic Ocean, were going to their graves.”2

Gertsl Yankl (Zvi Herts) Tsam (1835–1915) A former Cantonist who served in Siberia, Tsam appears to have been the only Jewish officer in the tsarist army in the nineteenth century Though he turned one of the worst companies of his regiment into one of the best, Tsam was denied promotion until 1893 when, after forty-one years of service, he was made a full captain shortly before he retired. Tsam was unusual in that he never converted to Christianity and took an active part in Jewish affairs. Credit: Saul Ginsburg.

Since most Jewish men at the time were married in their mid-teens, boys of twelve and under were often offered up to the authorities in order not to tear fathers and husbands away from their families. Between 1827 and 1854, about 70,000 Jews were conscripted, perhaps 50,000 of them minors. Perhaps as many as half the Cantonist recruits were converted to Christianity, passing out of their faith but remaining in the collective memory and folklore of the Jewish people as the Nikolaevskii soldatn.

In his attempt to convert the Jews, Nicholas I used the carrot as well as the stick. In 1841 he asked the “enlightened” (maskil) German scholar Max Lilienthal to try to persuade the Jews to accept the tsar’s offer of modern Jewish schools that would teach both secular and religious subjects. Believing in the good intentions of the government and the need to bring the benefits of European civilization to the benighted Russian Jews, Lilienthal traveled the Pale, seeking to persuade skeptical communal leaders to subscribe to the program. Most Jewish leaders correctly suspected that this was but another scheme to convert the Jews. Clearly the schools were to promote loyalty to the autocratic system. One of the texts in the required religion class (zakon bozhii) went as follows: “In our souls we know that it is as great a sin to disobey the word of the King as it is to transgress the commands of God, and Heaven forbid that we should be ingrates or desecrators of His Holy Name and do so in public or in private.”3

There was no rush to the new schools. Lilienthal left for America, where he served as a Reform rabbi. But by 1864 there were nearly 6,000 Jews in Crown schools (and over 1,500 attending Russian schools). These produced the first Russianized intelligentsia among the Jewish population. It is a great historical irony that many graduates of these state-sponsored schools, candidates for conversion to Russian Orthodoxy and loyalty to the autocracy, were caught up in the spirit of radicalism and rebellion infecting part of the Russian intelligentsia. They became the first Jews to seek ways of changing the tsarist system. Some were not consciously motivated by the plight of their own people, or at least they did not admit it; but others’ dissatisfaction with the system was sparked initially by the miserable situation of their coreligionists. The first Jewish graduate of a Russian university (1884), Lev Mandelshtam, exemplified the ambivalence felt by some Jews who had benefited from exposure to Russian culture and had escaped the Pale but could not escape their attachment to Jewishness and Jews.

I love my country and the language of my land but, at the same time, I am unfortunate because of the misfortune of all my fellow Jews. Their rigidity has enraged me, because I can see it is destroying their gifts. But I am bound to their affliction by the closest of ties of kinship and feeling. My purpose in life is to defend them before the world and to help them to be worthy of that defense.4

European culture was urged upon the Jews not only by the government, which wished to convert them, but also by Jewish reformers, who wished to “improve” them. The Haskalah or enlightenment had begun in Germany and had made its way eastward, passing through Galicia on its way to Russia. The maskilim, the enlighteners, sought to bring the benefits of European culture to the Jews and to infuse a new spirit into Jewish culture by reviving the Hebrew language—previously used only in religious texts and rabbinic responsa—for use in novels and scientific textbooks. Some of the maskilim advocated reforms in religion, while others were satisfied to maintain the traditional forms. Until the late 1870s the Russian maskilim maintained their faith in the goodwill of the tsarist author...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Creativity versus Repression: The Jews in Russia, 1881–1917

- 2 Revolution and the Ambiguities of Liberation

- 3 Reaching for Utopia: Building Socialism and a New Jewish Culture

- 4 The Holocaust

- 5 The Black Years and the Gray, 1948–1967

- 6 Soviet Jews, 1967–1987: To Reform, Conform, or Leave?

- 7 The Other Jews of the Former USSR: Georgian, Central Asian, and Mountain Jews

- 8 The Post-Soviet Era: Winding Down or Starting Up Again?

- 9 The Paradoxes of Post-Soviet Jewry

- Notes

- Indexes