![]()

PART I

MAKING SENSE OF

CONSCIENTIOUS CONSUMERISM

![]()

1 THE MAKING OF CONSCIENTIOUS CONSUMERS

Individual and National Patterns

THREE DECADES AGO A CONSUMER BUYING COFFEE WOULD HAVE found several roasts from a few major brands on the grocery store shelves, perhaps Maxwell House or Folgers in the United States or Douwe Egberts in Europe. Marketers had not yet invented the category of “specialty coffee,” so the price and quality differences between coffees were small. In addition, the global coffee market was regulated by the International Coffee Agreement, which stabilized the prices that coffee farmers around the world received for their beans. Fast-forward thirty years and that grocery shelf would include a variety of specialty coffees, some with labels promising fair or sustainable production methods. After the International Coffee Agreement collapsed in 1989, coffee prices became highly volatile. As coffee farmers in developing countries fell into extreme poverty, religious groups and peace activists in Europe and the United States developed a label to help support them—what would soon become the fair trade label. In response to the environmental effects of coffee production, organic, shade-grown, bird-friendly, and rain forest–friendly labels also became common.

In short, that grocery store aisle has become a place where consumers may express their consciences. Some choose mainly on the basis of price or quality, but others find those assurances of fairness or sustainability appealing. Why? Furthermore, might the chances of being a conscientious consumer depend on where you live are? In some countries those labels are found on only a few expensive varieties, but in others they are more mainstream.

In this chapter we examine the factors that make consumers in Europe and the United States more or less likely to engage in conscientious consumption, whether that means buying coffee because it is certified as fair trade and organic, choosing an environmentally sustainable piece of furniture, or avoiding a clothing company that exploits its workers. We use a simple and broad definition of conscientious consumption at this point, before probing deeper and looking at different products in subsequent chapters. Like many other researchers, our focus here is on two types of consumer behavior. First, consumers may boycott—or intentionally not support—a particular product or company for political or ethical reasons. Boycotts have been waged for hundreds of years, from the Boston Tea Party to grape boycotts called by farmworkers’ unions in the United States to boycotts in the UK against apartheid in South Africa. Whether organized or individual, conscientious consumption often means avoiding particular purchases.

More recently a second form of conscientious consumption has become widespread—that is, buycotting, or intentionally purchasing a product for political or ethical reasons. Consumers might support locally produced goods because they believe local economies are more sustainable or responsive than large-scale systems of trade. They might prefer a particular type of food—perhaps with an eco- or social label on it—that they believe is fairer or more sustainable than others. Or they may seek out clothes made domestically because they believe doing so reduces the chances that the garment was made in a sweatshop. These are just a few examples of buycotting. Our later chapters delve into these cases, but for now our initial goal is to develop a general portrait of conscientious consumption as practiced through individual boycotting and buycotting.

To begin this portrait, we have analyzed data from two large-scale surveys: the US “Citizenship, Involvement, Democracy” (CID) survey (conducted in 2005) and the European Social Survey (ESS) (conducted in 2002–2003).1 Both surveys were conducted through face-to-face interviews with probability samples of adult residents. The CID data comes from a sample of 1,001 individuals across all regions of the United States. The ESS data covers 26,981 individuals in nineteen European countries.2 Both surveys ask about boycotting and buycotting in the following way. Starting with a preface (“There are different ways of trying to improve things or help prevent things from going wrong”), individuals are asked, “During the last 12 months, have you done any of the following?” with answer choices that include “Boycotted certain products” and “Deliberately bought certain products for political, ethical or environmental reasons.” Obviously, these questions are asked in a quite general way, and this data does not allow us to probe for specific examples.3 Nevertheless, the data reveal variation in conscientious consumption that deserves to be explained. Only 18 percent of all respondents said they had boycotted in the past year, and only 29 percent said they had buycotted. By this measure most individuals in the United States and Europe are not especially conscientious consumers. Why are some people more likely than others to engage in conscientious consumption?

TOWARD A MULTILEVEL EXPLANATION

Most fundamentally we argue that explaining conscientious consumption requires attention to consumers’ motivations, beliefs, and opportunities. Consider the introductory example of buying coffee. How can we explain the action of a consumer who has paid two dollars more for fair trade–certified coffee? One factor might be a pro-social motivation, such as the desire to help coffee farmers in poor countries. In addition, and for this motivation to matter, the individual needs to hold a belief that fair trade really does help farmers, or at least that conventional coffee is exploitative. Finally, the greater the opportunity to buy fair trade–certified coffee—or on the flip side, the fewer the constraints—the greater the likelihood of the purchase occurring. Constraints on conscientious consumption exist at the individual level (in the form of disparities in discretionary income, for instance) but can also be embedded in the social context (as with differences in retail structures).4

By the end of this chapter we will have drawn a general portrait, rooted in our survey data, of the individual and contextual factors that make Europeans and Americans more or less likely to engage in conscientious consumption. We start with individual characteristics—not only motivations and beliefs but also variables such as income and social class. Many of these factors are salient, casting doubt on perspectives that treat ethical consumer identities as fully individualized—that is, divorced from “old” social structures such as social class (Beck 1994). However, individual differences are but a small part of the picture, since conscientious consumer activity varies quite substantially across countries. For our second set of analyses, then, we combine the ESS data with data on the political, economic, and cultural characteristics of different countries.5 Conscientious consumption, we find, is not just an individual behavior; it is structured by national differences in affluence, retail structures, and governance.

But first we begin by taking the example of fair trade a bit further. Markets for fair trade products have evolved quite differently in different countries. Through a brief comparison of the UK, Germany, and the United States, we illustrate how similar kinds of projects can evolve into different market structures. These structures of consumption have profound implications for individual acts. In addition to being revealing in their own right, these brief case studies pave the way to a cross-national analysis of our survey data.

Movements and Market Structures: The Example of Fair Trade

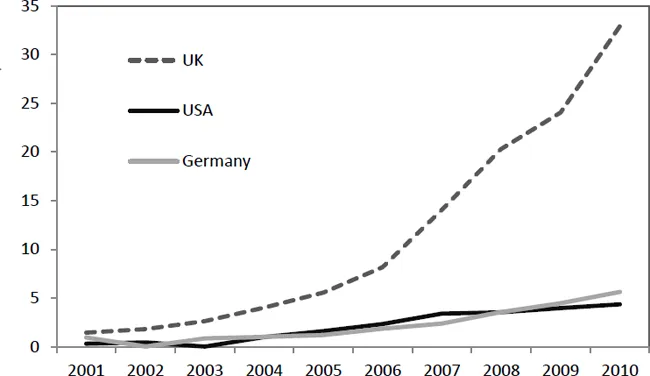

When it comes to the consumption of fair trade products, British consumers stand alone. In 2010 British consumers spent the equivalent of approximately $32 per capita on fair trade–certified products, compared to around $15 per capita in Sweden and Denmark, $10 per capita in the Netherlands, and $6–7 per capita in Belgium and France. German consumers spent $5 per capita and Americans spent only $4 per capita, although this was higher than some countries, such as Spain, where spending was less than $1 per capita (calculations based on data from FLO 2011). Fair trade–certified coffee, tea, chocolate, and fruit are widely available in the UK, and NGOs linked to the broader fair trade movement, such as Traidcraft and Oxfam, are well established there (Nicholls and Opal 2005). As figure 1.1 shows, growing sales of fair trade–certified products in the UK has far outpaced sales in Germany and the United States.

To some extent the UK’s leadership on fair trade could be attributed to critical voices in media and NGOs that stirred up debate about globalization. In addition, since the 1980s, British governments have promoted a neoliberal set of policy agendas that endorsed voluntary “corporate social responsibility” and consumer “responsibilization” (Kinderman 2012; Shamir 2008). On the other hand, British consumers are not the most “responsibilized” on all dimensions. When it comes to the consumption of organic food, the UK ranks far below Scandinavia, Germany, the United States, and France.6 The pattern becomes easier to understand if we look at how fair trade movements, retail structures, and consumer choices have co-evolved. If we compare the UK, Germany, and the United States, we see that what looks like a global market actually has nationally distinct movements behind it.

Figure 1.1: Per Capita Spending on Fair Trade–Certified Goods in the UK, USA, and Germany (in US $). Note: Values have been converted from € to US $ and standardized by population size as per capita spending. Sources: Fairtrade Annual Report (FLO 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011) and reports of national labeling organizations.

Common to all fair trade projects are the goals of (1) building stronger relationships between consumers and producers and (2) setting prices that provide a premium to producers (and are more stable than market prices). In addition, farmers and artisans typically receive some sort of subsidy (or “social premium”) to support infrastructure and services for their communities. In these ways the fair trade movement has sought to provide an alternative to both the vicissitudes of so-called free trade and the paternalism of charity. Of course, it has also been accused of retaining undesirable elements of both.7 (For our analysis of the consequences of fair trade certification in agriculture, see chapter 4.)

In the United States the fair trade movement dates to the 1940s, when Mennonite religious groups began a fair exchange program with makers of handicrafts in Puerto Rico (Grimes 2000). Soon after, the Church of Brethren began using a similar model to support World War II refugees in a “Sales Exchange for Refugee Rehabilitation” program. These projects would later fuel the creation of two religiously affiliated alternative trading organizations (ATOs)—Selfhelp: Crafts of the World and SERRV International—which acted as importers and retailers of handmade goods from developing countries (Grimes 2000). Selfhelp was later renamed Ten Thousand Villages, which now has hundreds of stores. In the UK fair trade can be traced to Oxfam—a famine relief charity founded in Oxford—which began selling handicrafts from developing countries as early as 1964 (Oxfam 2013). It did this in its own stores, which were initially designed for selling donated clothes and books. In Germany fair trade dates to 1972, when Campaign Third World groups were founded by Christian youth groups. After initially importing goods through a Dutch organization, the German groups founded their own alternative trading organization, Gepa, which allowed them to import, stock, and sell items on a much larger scale.

The existing infrastructure of Oxfam shops in the UK helped fair trade to get off the ground. In the United States and Germany there was a gradual shift from selling through church groups to setting up new fair trade shops, or “world shops,” mostly staffed by volunteers. Importantly, fair trade crafts in the United States and Germany remained closely tied to Christian organizations (Fridell 2004; Raschke 2009).

Starting in the late 1980s the fair trade movement became not only about crafts but about agriculture as well. In response to volatile world coffee prices, German Third World groups and American peace activists (via Equal Exchange) began selling what would be become fair trade coffee. British activists soon followed, developing the Cafédirect line of Fairtrade coffee. New organizations, like Transfair (United States, Germany, and others) and the Fairtrade Foundation (UK) emerged to standardize the labeling process (Linton, Liou, and Shaw 2004). As of 2001 the US market had 120 fair trade licensees (companies allowed to use the Fair Trade or Fairtrade mark on their products), Germany had 57, and the UK had 39 (Krier 2001). But by 2009 that number had increased by around 3.5 times in Germany, nearly 7 times in the United States, and roughly 10 times in the UK. Rapid growth in sales in the United States and Germany were no match for the nearly 1200 percent growth in the UK (as shown in fig. 1.1). Even as fair trade was becoming “mainstream,” mission-driven organizations (e.g., Equal Exchange, Gepa, and Cafédirect) persisted and expanded their offerings. As of 1997, sales by Oxfam and Traidcraft in the UK far outpaced sales from similar organizations in Germany and the United States (Martinelli 1998).

So why did fair trade grow so much more in the UK than in Germany or the United States? There are surely several pieces to a full answer. Matthias Varul (2009) argues that the legacy of British colonialism left British consumers with a peculiar sense of obligation. We argue that another important factor has to do with the legacies of early movements and their links to retailing structures, as described above. In the United States and (especially) Germany, the fair trade movement and its specialized distribution structures had a religious image. In the UK there had not been a broad base of “world shops.” Oxfam shops had been used, but these were never exclusively focused on fair trade. This left more leeway for the “branding” of fair trade and its mainstreaming through supermarkets. British fair trade advocates successfully lobbied large retailers to stock Fairtrade-certified goods, and some supermarket chains even transformed their own coffee and chocolate brands to Fairtrade (Barrientos and Smith 2007). There has been a trend toward concentration in British retailing—toward a small number of very large retailers with big investments in their own brands—and this likely amplified the efforts of fair trade activists, much as it did for the anti-GMO activists studied by Rachel Schurman and William Munro (2009).

Returning to our opening vignette about a coffee purchase, a consumer in a grocery store in the UK would find numerous options for fair, ethical, or sustainable coffee. A consumer with similar motivations and beliefs in the United States or Germany would face a different set of opportunities for conscientious consumption. This leads us to ask about the individual and contextual factors that shape these consumers’ behavior. Our analysis of survey data sheds considerable light on this issue, allowing us to look at both individual-level and national-level factors.

WHO ENGAGES IN CONSCIENTIOUS CONSUMPTION? INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL PATTERNS

Motivations and Beliefs

What motivates conscientious consumer behavior? This question has spawned a range of answers, emphasizing factors from environmentalism to particular conceptions of morality (Arndorfer and Liebe 2013; Copeland 2014; Daugbjerg and Sønderskov 2012; Guido, Pino, and Prete 2009; Neilson 2010; Shaw 2005; Stolle, Hooghe, and Micheletti 2005; Sunderer and Rössel 2012). Studies of particular forms of political consumption, such as buying fair trade goods, have also highlighted the influence of specific attitudes (Guido 2009; Ozcaglar-Toulouse, Shiu, and Shaw 2006; Shaw 2005) and identities (Arndorfer and Liebe 2013; DuPuis 2000; Varul 2009). In addition, there is some evidence that religious identities matter, with Americans who were raised as Protestants being more likely to buycott and those who reject evolution (in favor of a literal biblical account of creation) being less likely to boycott (Starr 2009).

But the most widespread general argument is that conscientious consumption reflects deeper “post-materialist” orientations, such as self-actualization and autonomy, that become possible when individuals move beyond “materialist” concerns, such as economic well-being and physical security. By some accounts rising affluence has led industrial democracies to undergo a fundamental value shift over the past decades from materialist to post-materialist concerns, including environmental protection, creative expression, and human rights (Inglehart 1997; Norris 2002). One need not subscribe to a full value-shift theory to appreciate that individuals with more post-materialist values may be more likely to be conscientious consumers. Indeed, our analyses find that among European consumers, individuals who express strong post-materialist values—that is, “understanding, appreciation, tolerance and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature”—are far more likely than others to boycott or buycott. Holding other factors constant, an increase of one standard deviation in the measure of post-materialism increases the likelihood of buycotting by 7 percent and the likelihood of boycotti...