- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

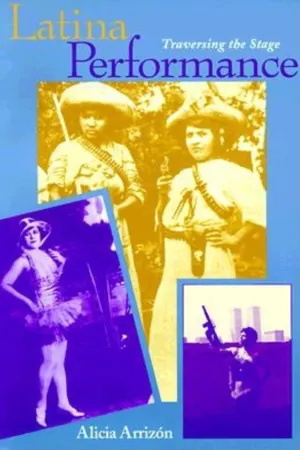

A study exploring the role of Latina women in theater performance, literature, and criticism.

Arrizón's examination of Latina performance spans the twentieth century, beginning with oral traditions of corrido and revistas. She examines the soldadera and later theatrical personalities such as La Chata Noloesca and contemporary performance artist Carmelita Tropicana.

Latina Performance considers the emergence of Latina aesthetics developed in the United States, but simultaneously linked with Latin America. As dramatists, performance artists, protagonists, and/or cultural critics, the women Arrizón examines in this book draw attention to their own divided position. They are neither Latin American nor Anglo, neither third- or first-world; they are feminists, but not quite "American style." This in-between-ness is precisely what has created Latina performance and performance studies, and has made "Latina" an allegory for dual national and artistic identities.

"Alicia Arrizón's Latina Performance is a truly innovative and important contribution to Latino Studies as well as to theater and performance studies." —Diana Taylor, New York University

"Arrizón's . . . important book revolves around the complex issues of identity formation and power relations for US women performers of Latin American descent. . . . Valuable for anyone interested in theater history and criticism, cultural studies, gender studies, and ethnic studies with attention to Mexican American, Chicana/o, and Latina/o studies. Upper—division undergraduates through professionals." —E. C. Ramirez, Choice

Arrizón's examination of Latina performance spans the twentieth century, beginning with oral traditions of corrido and revistas. She examines the soldadera and later theatrical personalities such as La Chata Noloesca and contemporary performance artist Carmelita Tropicana.

Latina Performance considers the emergence of Latina aesthetics developed in the United States, but simultaneously linked with Latin America. As dramatists, performance artists, protagonists, and/or cultural critics, the women Arrizón examines in this book draw attention to their own divided position. They are neither Latin American nor Anglo, neither third- or first-world; they are feminists, but not quite "American style." This in-between-ness is precisely what has created Latina performance and performance studies, and has made "Latina" an allegory for dual national and artistic identities.

"Alicia Arrizón's Latina Performance is a truly innovative and important contribution to Latino Studies as well as to theater and performance studies." —Diana Taylor, New York University

"Arrizón's . . . important book revolves around the complex issues of identity formation and power relations for US women performers of Latin American descent. . . . Valuable for anyone interested in theater history and criticism, cultural studies, gender studies, and ethnic studies with attention to Mexican American, Chicana/o, and Latina/o studies. Upper—division undergraduates through professionals." —E. C. Ramirez, Choice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Latina Performance by Alicia Arrizón in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Latin American & Caribbean Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780253028150Notes

1. In Quest of Latinidad

1. Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” Boundary 2, no. 12 (1984), p. 336.

2. Diana Taylor, “Opening Remarks,” in Negotiating Performance: Gender, Sexuality, and Theatricality in Latin/o America, ed. Diana Taylor and Juan Villegas (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), p. 9.

3. One serious omission in Negotiating Performance is co-editor Juan Villegas’ failure to acknowledge the importance of race and queer theory in his conclusion to the volume.

4. David Roman and Alberto Sandoval, “Caught in the Web: Latinidad, AIDS, and Allegory in Kiss of the Spider Woman, the Musical,” American Literature 67, no. 3 (September 1995) pp. 553–585.

5. José Cuello, “Latinos and Hispanics: A Primer on Terminology,” Nov. 19, 1996, in Midwest Consortium for Latino Research (“[email protected]”). Note that these references were posted as a service to MCLR subscribers. José Cuello is an Associate Professor of History and Director of the Center for Chicano-Boricua Studies at Wayne State University in Detroit.

6. Judith Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (New York: Routledge, 1997), p. 74.

7. John O’Sullivan, quoted in Albert K. Weinberg, Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1935), p. 145.

8. Rodolfo Acuna, Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, 3rd ed. (New York: Harper Collins, 1988), p. 20.

9. Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Tide of Color: Against White World-Supremacy (New York: Scribner’s, 1920).

10. Acuna, Occupied America, p. 240.

11. Cherríe Moraga, The Last Generation: Prose and Poetry (Boston: South End, 1993), p. 156.

12. Ibid., p. 157.

13. Suzanne Pharr, Homophobia: A Weapon of Sexism (Little Rock: Women’s Project, 1988), pp. 16–17.

14. Cherríe Moraga, Loving in the War Years: Lo que nunca paso por sus labios (Boston: South End, 1983), pp. 139–140.

15. Moraga, The Last Generation, p. 148.

16. Ibid., p. 159.

17. Sue-Ellen Case, The Domain-Matrix: Performing Lesbian at the End of Print Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 164.

18. Moraga, The Last Generation, p. 150.

19. Ibid., p. 164.

20. Juan Flores, Divided Borders: Essays on Puerto Rican Identity (Houston: Arte Publico, 1993), p. 14.

21. Ibid., p. 189.

22. Sandra Maria Esteves, Yerba Buena (New York: Greenfield Review, 1980).

23. Puerto Rican feminists and other Latinas look to Julia de Burgos (1914–1953) as an important precursor. Burgos7 poetry has been reprinted in political and educational pamphlets distributed both on the mainland and in Puerto Rico. The first shelter for battered women on the Island was named after Burgos. In Yerba Buena, Esteves includes a poem dedicated to Burgos. Some of the lines are:

For you, Julia, it will be too latebut not for meI live!

24. Boricua is a term that expresses the vernacular signification of Puerto Rican identity. Being a “boricua” or “borinqueño” involves those elements which are constitutive of mestizaje and hybridity. A boricua identifies mostly with the African and/or indigenous heritage, counteracting the standardization and the estrangement of dominant culture.

25. Sandra Maria Esteves, Bluestown Mockingbird Mambo (Houston: Arte Público, p. 43). One other collection of Esteves’ poetry has been published: Tropical Rain: A Bilingual Downpour (New York: African Caribbean Poetry Theater, 1984).

26. Bluestown Mockingbird Mambo, p. 43.

27. Juan Flores, Divided Borders, p. 187.

28. Gloria Anzaldúa, “Chicana Artists: Exploring Nepantla, el lugar de la frontera,” NACLA: Report on the Americas 27, no. 1 (1993), p. 39. This number was a special issue entitled Latin American Women: The Gendering of Politics and Culture.

29. Norma Alarcón, “Latina Writers in the United States,” in Spanish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Source Book, ed. Diane E. Martin (Westport: Greenwood, 1990), p. 557.

30. Seymour Hersh, “Censored Matter in Book about CIA Said to Have Related Chile Activities,” New York Times, September 11, 1974.

31. Writer-director Gregory Nava deals with these issues in his film El Norte (1984). In this film, a brother and sister leave troubled Guatemala for the U.S., “the land of many opportunities.” They cross borders illegally from Guatemala to Mexico, then from Mexico to California. With the help of a coyote, they reach Los Angeles. Once they have made it to the “promised land,” their problems are not over; they simply begin to take a different shape.

32. Coco Fusco, “Norte: Sur—A Performance-Radio Script by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gömez-Pena,” in Fusco’s English Is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas (New York: New Press, 1995), p. 170.

33. Martha E. Gimenez, “Latinos/Hispanics… What Next! Some Reflections on the Politics of Identity in the U.S.” Heresies 27 (1993), p. 40.

34. Ibid., p. 42.

35. Gladys M. Jiménez-Muñoz, a Puerto Rican of African descent, notes that the denial of an African heritage is more noticeable among black Latinas/os and people of darker-skinned pigmentation, “where the emphasis is on non-African identifications: either toward the non-existent ‘Indian’ element among mulattoes and blacks in the Caribbean or toward the ‘whiter’ element among the mestizo and mulatto populations of Mexico, Central America, and South America.” Jiménez-Muñoz, “The Elusive Signs of African-ness: Race and Representation Among Latinas in the United States,” Border/Lines 29, no. 30 (1993), 11.

36. Failure to acknowledge African roots, Jiménez-Muñoz argues, makes it impossible for U.S. Latinos to fully comprehend their contemporary experience: “like our slave ancestors—particularly the captive women—today in the United States we continue to live in multiple ways the experience of exclusion, deportation, refusal, repudiation, erasure, ignorance, and attack.” Ibid., p. 15.

37. Diana Taylor, Negotiating Performance, p. 8.

38. Ibid.

39. Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres, eds., Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), p. 7.

40. Ibid.

41. Chiqui Vicioso, “An Oral History,” in Breaking Boundaries: Latina Writing and Critical Readings, ed. Asunción Horno-Delgado, Eliana Ortega, Nina M. Scott, and Nancy Saporta Sternbach (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1989), p. 231.

42. For example, consult Angela Davis, Women, Race and Class (London: Women’s Press, 1982). Davis writes that black women suffer a double threat in economic production when racism and sexism merge to assign black women to low-paid jobs. However, she points out that a black woman’s consciousness of oppression and her activism contest white feminist theory. Davis has criticized the concept of a culturally homogeneous black woman, addressing the historical subject who, in her own (Davis’) discoveries, has resisted white domination.

43. Gloria Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (New York: Kitchen Table, 1981), p. xxiv.

44. Norma Alarcón, “The Theoretical Subject(s) of This Bridge Called My Back and Anglo-American Feminism,” in Making Face, Making Soul/haciendo caras: Cre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- One In Quest of Latinidad: Identity, Disguise, and Politics

- Two The Mexican American Stage: La Chata Noloesca and Josefina Niggli

- Three Chicana Identity and Performance Art: Beyond Chicanismo

- Four Cross-Border Subjectivity and the Dramatic Text

- Five Self-Representation: Race, Ethnicity, and Queer Identity

- Final Utter-Acts

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index