![]()

1

Portraits

LESSON 1: ON BEING A SUBJECT

I want to begin by thinking about portraits, and as a first task, I ask you to find a pencil and paper and take a moment to draw a person. It is good for you to do this on your own so that you can notice what issues are raised for you by this activity. I often ask my students to do this exercise in my classes, and the image they most often draw is a simple figure with a “smiley face,” waving. Typically it is a man (or so one can conclude from the familiar conventions about how to portray men and women through simple figures). Although minimal, the image portrays emotion, and a happy emotion at that; it also portrays gender and, typically, age; most often, my students draw a young adult rather than a child or a person in old age. Sometimes the figure is depicted in trousers, a shirt, and a tie, thus further indicating that he belongs to the modern world. Inasmuch as such a figure is easily recognized, this image seems, at a basic level, to succeed in portraying a person.

The human practice of making portraits is quite ancient, with long traditions of portraying gods and leaders, for example, in Mesopotamia, China, and Egypt. With the development of coinage in Greece and the Mediterranean world, it became common to portray rulers on coins. The practice of portrait painting was especially cultivated by the great Renaissance oil painters, such as the Flemish Jan van Eyck and the German Hans Holbein. Let us now consider more well-developed examples of portraiture, beginning with one from c. 1480 by the Flemish painter Hans Memling.

This work (figure 1.1) is commonly referred to as Man with a Roman Coin, but it is often thought to be a portrait of Bernardo Bembo, a political figure in Renaissance Venice. Whether or not the portrait is actually of this historical individual, this person portrayed is, again, clearly a man, and, again, older than, say, twenty years old. He is Caucasian, and he is clothed in garments that suggest he is an affluent citizen. Indeed, from the details of his skin, hair, and clothes, an educated physician or historian could probably determine a great deal about his health, social standing, and more. It is interesting, too, that in his hand he holds a coin that itself contains a portrait, that of Nero, the Roman emperor. This portrait of Nero is in profile, and this feature draws our attention to the fact that our earlier portraits—our imagined simple drawing and the image of Bembo himself—are frontal views of the person portrayed. Noticing this contrast alerts us to the fact that we could portray a person differently than in a fully frontal view of the face one encounters in a smiling stick figure—a person could be portrayed from the side, from the back, from below, from behind.

Consider next a work by Rembrandt (figure 1.2), which in its contrast with other portraits can draw our attention to another feature of portraiture. The man portrayed in this etching is clearly blind, a fact communicated to us by his facial expression of seeking, by his use of a cane and an outstretched hand to find his bearings, and by his being accompanied by a friendly dog that is perhaps troublingly underfoot but on which he quite possibly depends. If we look closer at the image, we notice two more clues that the man is blind: the spinning wheel has fallen, perhaps because the man knocked it over, and although he is reaching forward, his hand touches the wall, missing the doorway that he was likely seeking. Indeed, this etching is titled The Blindness of Tobit (1651). I draw your attention to that because, if we return to Man with a Roman Coin, we can see that the man portrayed there seems clearly not to be blind: that picture depicts a seeing man. In addition, the blind man in Rembrandt’s etching, whom we see from the side, is active, whereas our earlier images portray someone in a still pose.

That the simple figure of a standing, adult man seen from the front, with which I began this discussion, is so often what people produce when I ask them to draw a person suggests that it is by far the standard presumption, at least among average Westerners these days, that something like it “is” how to portray a person; thus although the quality can of course be improved (as, for example, in the richly developed portrait by Memling), this standing adult man, seen from the front, is presumed to be an accurate image of a person. What our comparisons allow us to see, however, is that this initial image is not neutral, but is instead a prejudicial image; it is a selective image that privileges certain aspects of the person while excluding various other aspects that are quite essential to the person. The opposed sorts of portraits (of Nero and Tobit) are equally accurate: we do have profiles and backsides, we do engage in different activities of which sitting or standing still is only one (rather forced) option, we are differently “abled” and do not automatically have the same capabilities as each other. This comparison can lead us now to focus not on the accuracy of the portraits we see—not on what they do portray about the person—but on what they exclude. With this new critical perspective in place, let us consider the string of portraits again and ask of them all what they exclude. Diego Velázquez ‘s famous painting of the family of Philip IV of Spain, commonly referred to as Las Meninas or The Family of Philip IV (1656; figure 1.3), can provide us with an answer.

FIGURE 1.2

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, Dutch, 1606–69

The Blindness of Tobit, 1651

Etching with touches of drypoint, 6 ¼ × 5

in. (15.9 × 12.9 cm)

Minneapolis Institute of Art, William M. Ladd Collection

Gift of Herschel V. Jones, 1916 P.1,241

Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art.

On the one hand, we could describe this artwork as a portrait of a painter facing his canvas, and we could note about this painter the various characteristics we saw in the other portraits: his gender, his emotion, his age, his race, his style of dress, his position, his mode of activity, and so on. His activity, however, makes another feature even more obvious. Clearly the painter is looking at his subject, and whenever you view the image, you are clearly in the position of the one being painted—the one being portrayed (just as this book aims to be about your experience). Indeed, then, what is visible in this image is what you would see if you were being painted. This is a portrait of what you would experience if your portrait were being painted. Let us imagine that the painter portrayed in the image is Velázquez himself. In that case we would have to say here that Velázquez, in this image, has indeed produced a portrait of the one he is looking at, but he has done it by portraying that person as a subject, and not as an object.

If we look back at all of our earlier portraits, we can see that in each case the person is portrayed as an object; that is, the person is not me, but is someone else who is the object of my experience. And it is striking, as I noted earlier, that this seems to be our first reaction, our first presumption in portraying a person. But, on the contrary, our primary experience of a person is our own experience of being ourselves. First and foremost, for each of us, a person is a subject, the experiencing from the inside of a perspective within which others figure as objects. Indeed, to experience another person as a person is to experience her or him as a subject. This is what was hinted at earlier when we noted that the persons in the portraits painted by Memling and Rembrandt are apparently seeing and blind, respectively. In making this recognition, we acknowledge that each person portrayed is experiencing, is living out his experience as an encountering of other things as objects within the context of a more fundamental experiencing of himself as a subject, a subjectivity. This subjectivity, however, though acknowledged, is not portrayed in those portraits. Though we acknowledge that to be a person is to be a subject, we portray the person as an object.

FIGURE 1.3

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Spanish, 1599–1660

Las Meninas or The Family of Philip IV, 1656

Oil on canvas, 318 × 276 cm.

Museo Nacional del Prado, Inv.: P01174

© Museo Nacional del Prado.

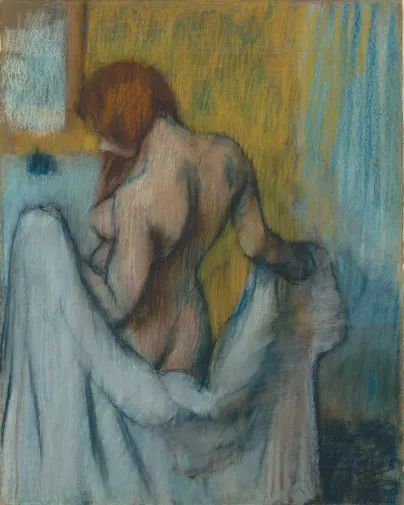

Let us use the lesson we learned from Velázquez to reconsider the earlier portraits. We noted that the person portrayed in each portrait could be portrayed from the front, from the side, from behind, and so on. But let us note what is implicit in such portrayals. To portray the person from the side is to portray that person as he or she would be seen by another person looking on from that side. Velázquez in Las Meninas used the portrait of the painter as a way to draw our attention to our own necessary position as observers: only if we were looking on from the position of the one being painted could we see the painter in that position. Similarly, each portrait of a person implies the point of view within which that person appears the way he or she does. Precisely insofar as each portrait portrays the person as an object, it implicitly portrays the subject for whom the person appears in this way, for whom it is an object. Consider, for example, the pastel image by Edgar Degas titled Woman with a Towel (1894; figure 1.4).

This artwork is a portrait of someone engaged in an activity that is normally performed privately. In addition, the woman is portrayed from behind, so that in her nudity she is exposed to a gaze that she herself does not see. The portrait of the woman, in other words, implies the intimate perspective of a close friend or perhaps a voyeuristic gaze that “spies” on another without subjecting itself to a reciprocal vulnerability; in either case, it is only from a specific and privileged perspective that one could have this view (as, indeed, the view in Velázquez’s Las Meninas could, presumably, only be had by the king himself, who would seem to be the most plausible candidate for the person having his portrait painted in such a situation). In either interpretation, this image—explicitly the portrait of the woman being viewed—is implicitly the portrait of the viewing gaze. In taking up this perspective, are you adopting the loving view of an intimate companion? Or, on the contrary, are you taking up the (paradigmatically male) perspective invited by so many familiar cultural images of a gaze that comfortably retreats from involvement and bodily engagement and instead uses its detached, scrutinizing, and judging power to oppress—an objectifying gaze that tries to dominate by asserting its power to reduce the other to “mere” objectivity, to reduce the other to the finitude of its “thingly” specificity? Just as the truly intimate portrait, perhaps paradigmatically encountered in private photographs, implies the intimate, loving gaze of the one to whom it offers itself, and just as the voyeuristic image so familiar in exploitative advertising is simultaneously a portrait of the voyeuristic gaze, so are all the earlier portraits we considered implicitly portraits of viewing subjects: portraits, that is, not of the person portrayed in the picture as an object, but of the one for whom this portrait would be the form its vision takes.

FIGURE 1.4

Hillaire-Germain-Edgar Degas, French, 1834–1917

Woman with a Towel, 1894

Pastel on cream-colored wove paper with red and blue fibers throughout, 37 ¾ × 30 in. (95.9 × 76.2 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.37)

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition, then, to teaching us to distinguish being a subject from being an object, Las Meninas also alerts us to something about our own perceiving. In considering an appearance, one is always considering an appearance to someone or an appearance for someone. We can thus describe the determinate features of the appearance—its “objective” features, so to speak—and we can also describe the perspective for which it is an appearance, the stance of subjectivity implied by it. We can do this with the portrait—which is always thus a portrait of a point of view—and we can equally do it with respect to what appears to us in our ongoing experience. Las Meninas led us to recognize our own living experience as subjects, and just as we were then able to see that every portrait in principle invites the same self-reflection by the viewer, so too can we now recognize that any determinate aspect of the world that is appearing to us, insofar as it is appearing to us, implicitly points to our own subjectivity. Thus, here again, we can focus on the determinate features of what appears, or we can read back to the subjectivity implied in the determinate features of what appears; that is, we can focus on the perspective for which it is an appearance. Whatever appears to me always shows itself in a way that is responsive to my point of view, which is a point of view always situated in a specific place, at a specific time, within a specific culture, in a specific emotional state, and so on. Who I am implicitly appears in what I perceive.

LESSON 2: THE EVENT OF EXPERIENCE AND THE ADVENT OF MEANING

Now that we have discovered the field of subjectivity, the experience “from the inside” of being a person, let us explore its characteristics. First and most important, it is pervasive. In other words, everything for us is within this experience. The very condition of anything appearing to me is, indeed, that it appears to me. This means that everything with which I have any dealings—practical, imaginary, scientific, nutritional, emotional, educational, sexual—is always mediated by this self-experience; everything is always available to me only insofar as it occurs within the experience of my being a subject.

This experience of myself is both the possibility of all my other experience—all my experience of “other”—and the limit of my experience. In a fundamental way, I will always remain inexplicable to myself, because there is no possibility of my getting “behind” myself to see where I came from or how I came into being. It is only when I am already happening that the field of possible experience—the field of asking questions and receiving answers—is available. For this reason, my experience, my being a subject, always takes the form of an event, a spontaneous happening, inexplicable to itself on the basis of anything beyond itself, inasmuch as any explanation by some such “beyond” is always an explanation within the terms of my experience, an explanation within the happening it is supposed to explain.

In a fundamental way, then, our experience, our subjectivity, is always wrapped up with itself, and nothing can break us out of our insularity. Perhaps this is suggested by the figures in Luis Jacob’s photographic image, The Inchoate Ensemble (2007; figure 1.5). The figures belong to the same space, but they relate only through a kind of blind touch within the medium of an opaque fabric that both connects and separates them. Though surrounded by others, these subjects seem locked forever within themselves, every push to the outside simply a reconfiguring of their own insularity.

As we have already seen, however, this apparent self-definedness of our subjectivity is a bit misleading. Describing our experience as “self-defined,” suggests that we are in charge of the “sense” of our experience. In fact, though, the event-like character of our happening entails that we are always opaque to ourselves, always encountering in the “fact” of ourselves an inexplicable mystery. In other words, although I might say that “all this” is “inside” me, the meaning of this claim remains quite unclear. We might just as well say, in fact, that this self is only outside itself, because at its heart it encounters an irremovable mystery.

FIGURE 1.5

Luis Jacob, Canadian (born in Peru), 1971–

The Inchoate Ensemble, 2007

Chromogenic print, 101.6 × 129.3 cm (40″ × 50.9″)

Courtesy Bir...