- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

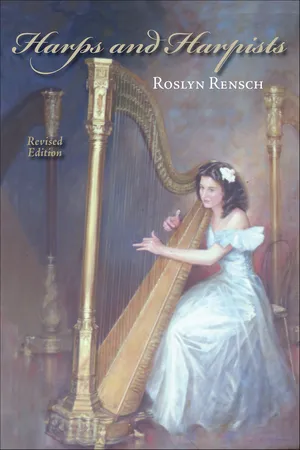

Harps and Harpists, Revised Edition

About this book

Revising her classic 1989 book Harps and Harpists, Roslyn Rensch expands her authoritative history of this timeless instrument. This lavishly illustrated edition, with 137 black-and-white images and 24 color plates, surveys the progress of the harp from antiquity to the present day. The new edition includes two new chapters; an extensive bibliography and index; personal anecdotes of the author's studies under Alberto Salvi; and an appendix on the Roslyn Rensch Papers and Harp Collection, which are housed at the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Harps and Harpists, Revised Edition by Roslyn Rensch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

The Harp in the Ancient World

1

The Beginning

OUR KNOWLEDGE of the harp in the ancient world would be meager indeed without pictorial evidence, since only a small number of these early musical instruments now survive. Fortunately, representations of harp-like musical instruments can still be found in a variety of ancient paintings and sculpted reliefs. Attention to these art works, as well as surviving harps, will shed some light on the early history of the harp.

MESOPOTAMIA

Early evidence of the harp in Mesopotamia is provided by archaeological finds of objects attributed to the Sumerians, a non-Semitic people who, by the fourth millennium B.C., had settled in the lower valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Semitic nomad shepherds from the western desert also established themselves in this vicinity and in subsequent centuries domination of the area shifted between dynasties from the Sumerian city of Ur and those of the Semitic kingdoms of Akkad and Babylon; there were also periodic conquests from neighboring territories. Finally the Assyrians of northern Mesopotamia overcame southern resistance and established an empire which, during the first millennium B.C., ruled most of the Near East for almost three centuries. Despite these changes, interest in the harp apparently endured and the partial remains of a few harps as well as some representations of the instrument are extant. The survival of these objects seems almost miraculous, since the physical climate of western Asia, like its volatile political climate, is hardly conducive to preservation.

Mesopotamian clay tablets of c. 2800 B.C. include as a pictographic sign a simple linear carving of a harp with three strings. Representations of musicians with harps occur even earlier on limestone plaques and on seals. All of these examples are quite small but it is possible to see that the harps, while bow-shaped in general outline, differ slightly in detail.1

1.1. A bearded harp player is represented on a votive plaque less than eight inches square, c. 3000 B.C., Khafaje (Iraq). Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

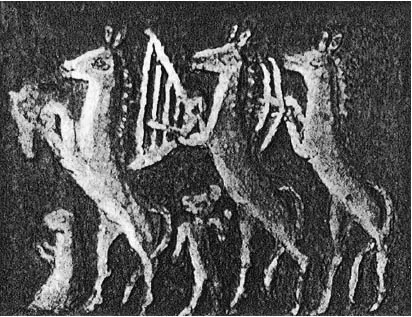

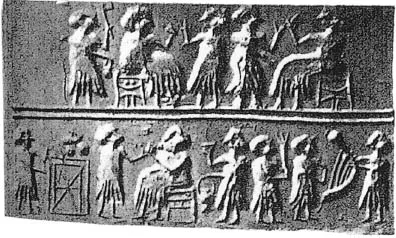

On a votive plaque less than 8 inches (20.3 cm) square, one of a pair of bearded figures stands while playing a harp (fig. 1.1). Presumably the harpist and the figure facing him, with arms crossed, are performing at a banquet honoring the seated figures represented in the top band of the plaque. Dated c. 3000 B.C., the plaque was found in the vicinity of the Sin Temple at Khafaje, a small city east of the Tigris River. Other depictions of harps have been found in the vicinity of Ur, once a city of great importance in South Babylonia and the seat of the Sumerian dynasties. On a seal from Ur, where a trio of onagers is represented cleverly prancing along on their hind legs, one plays a small harp (fig. 1.2). On another Ur seal, a larger harp, with a mushroom form capping its string arm, is held by a person standing with other musicians (fig. 1.3).2

1.2. One of three onagers plays a small harp. Impression (much enlarged) from a seal found at Ur. University of Pennsylvania Museum (Plate V, no. 5 [id. Galpin]).

During the extensive excavations of the Royal Cemetery at Ur, conducted in the 1920s by C. Leonard Woolley,3 the remains of several stringed instruments were found. Museum restorations have produced handsome musical instruments truly worthy of being played for important religious or court ceremonies. However, an example of the Ur instrument at the University Museum, Philadelphia, elegantly decorated with the head of a bull covered with gold and trimmed with a beard of lapis lazuli, is more accurately designated as a lyre (fig. 1.4). The instrument is rectangular in form and its strings, relatively equal in length, fan out over the soundbox. In shell inlay on the soundbox end just below the bull’s head, in one of several fanciful scenes probably illustrating myths or legends, a seated animal (perhaps another onager) plays a similar lyre. Instead of hoofs the animal has human hands whose fingers pluck the strings.4

1.3. On a seal from Ur, a standing figure holds a harp with a mushroom form capping its string arm. University of Pennsylvania Museum (Plate II, no. 4 [id. Galpin]).

The British Museum’s Ur exhibit, handsomely remounted since the 1960s, includes several restored lyres and a new reconstruction of a harp found in the grave of the queen. For some time this particular exhibit suffered from the problem that a lyre and a harp, long buried together, were restored as one musical instrument. A separation of these two forms has at last been achieved and the “Harp of Ur” now appears as a boat-shaped harp of eleven strings (fig. 1.5). Some remains of two other harps were found in the queen’s grave. One instrument originally had fifteen strings. The string pegs of these harps were of precious metals and each string arm terminated in a cap of gold or silver. This feature resembles the mushroom form noted on the string arm of the Ur seal harp (fig. 1.3). Most recent archaeological study indicates a date of c. 2600–2350 B.C. for the foregoing examples.

1.4. Lyre (restored) from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, c. 2600–2350 B.C. University of Pennsylvania Museum (neg. #;T35-2171).

1.5. Harp (restored) from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, c. 2600–2350 B.C. © Copyright The Trustees of The British Museum.

On a vase fragment of green steatite, of an even earlier period (c. 3100–2900 B.C.), a pair of kilted musicians, with feathers in their hair, play bow-shaped instruments of seven and five strings, respectively (figs. 1.6, 1.7). Both instruments are held horizontally with the strongly arching string arm in the forefront and the soundbox tucked under the player’s left arm.5 This manner of holding bow-shaped harps can still be seen in some parts of Africa. The vase fragment was found at Bismaya (the ancient city of Adab).

Harps that are angular, rather than bow-shaped, are represented on some terracotta plaques of the second millennium B.C. from Ishchali in the ancient independent kingdom of Eshnunna. A plaque only 5 inches (12.7 cm) long depicts a seated musician playing this instrument (fig. 1.8). Here the large soundbox, and the sturdy pole that serves as a string arm, are obviously two separate parts which join at an angle, and the soundbox (held vertically against the musician’s body) rises above the string arm.

Other small plaques of the same period show an angular harp of similar design, and also an arched harp, held with the soundbox in a horizontal position while it is played. Both seated and standing musicians are represented with these horizontally held harps and each uses a plectrum to sound the harp strings. A plectrum does not seem to have been used in playing the vertically held angular harp. While no examples of this harp survive in Mesopotamia, the instrument probably served as a prototype for the angular harps found in Egypt.

1.6. Bow-shaped stringed instruments are played by two musicians. Vase fragment c. 3100–2900 B.C., from Bismaya (Iraq). Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

1.7. Drawing of musicians on Bismaya vase fragment. (After Curt Sachs, Musik der Antike, in Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, Potsdam, 1934).

Relief carvings from the first millennium B.C., discovered at Nineveh and Nimrod, in the ruins of the once great palaces of the Assyrians, include additional examples of the angular harp. These reliefs, often quite large continuous scenes, abound with a variety of carefully carved details. Both vertically and horizontally held angular harps are represented in left or right profile. The string arms of some horizontally held instruments terminate in the carving of a human hand, which points heavenward when the harp is played.

1.8. A seated musician plays an angular harp. Terracotta plaque, 2025–1763 B.C., Ishchali (Iraq). Courtesy of The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

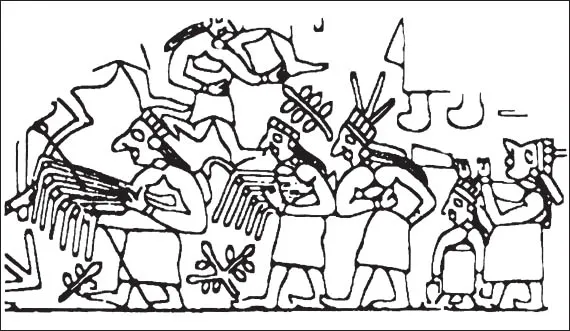

In a Nineveh palace relief, now in the British Museum, a musician playing a vertically held angular harp attends the powerful Assyrian ruler Assurbanipal and his queen as they dine al fresco. With admirable composure the harp player stands near a tree—from the upper branch of which dangles the severed head of the late ruler of Elam (fig. 1.9). In another Nineveh palace relief, eight harp players are included among the Elamite musicians assembled to greet Assurbanipal.6 Seven of the harps are held with the soundbox rising vertically above the string arm, while one instrument is held horizontally. The strings of the former instruments are finger plucked but the musician playing the latter instrument uses a long baton-like plectrum. The men and women (or perhaps eunuchs) represented here as harpists are either marching or dancing.

1.9. An angular harp is played near a tree that bears a severed head. Limestone relief, c. 650 B.C., Nineveh Palace. © Copyright The Trustees of The British Museum.

While it is never advisable to interpret a work of art too literally, the Assyrian carvings suggest that these harp players might vary their music by plucking the strings near the string arm with the fingers of the right hand and plucking nearer the soundboard with those of the left hand. Harmonics and muffling, both part of the present-day harpist’s repertoire, may also have been employed. Certainly the muffling of some strings may have been desired if the plectrum was used to sweep across the strings of the horizontally held harp. In both versions of the harp, the strings are wrapped around the string arm, augmented by tassel-ended cords. The harps in these stone carvings have as many as twenty-one strings but, while this suggests a possible range of several octaves, the scales actually used in tuning the harps have yet to be determined. Curt Sachs, after studying the hand positions of the seven Elamite musicians playing the vertically held harps, suggested they were playing fifths and octaves on pentatonically tuned instruments. More recent research, based on an ancient Babylonian treatise on harp tuning, confirms a pentatonic and later a heptatonic tuning.7

EGYPT

Archaeological excavations in Egypt make it evident that harps were of great importance in the cultural life of the ancient Egyptians. From prehistoric times Egyptian life evolved around the Nile, a long and constant river, running south to north and periodically overflowing its banks to enr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Part I The Harp in The Ancient World

- Part II The Non-Pedal Harp in Western Europe and North America

- Part III The Pedal Harp in Western Europe and North America

- Part IV Retrospection and The Future

- Appendix

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index