![]() Part 1. Introduction

Part 1. Introduction![]()

1

Body Art in Banaras

EVERY ONE OF US gets dressed in the morning, every day of our lives. Clothing is one of the principal ways by which we express at once our personal identities and our culture. Dress, along with architecture and food, fulfills basic human needs for protection and creativity, while responding to environmental and social conditions. Since all people engage in these shared mediums of expression, one way to understand and compare cultures—and to see regional, local, and personal differences within cultures—is to examine specific modes of clothing, housing, and feeding the body. Schools and museums often utilize this basic triad in introducing children to the diversity of the world’s populations.1 But in contrast to the study of vernacular architecture, and, to a lesser extent, the study of foodways, the examination of everyday clothing is not yet fully developed. Surveys of national dress tend to generalize, homogenize, and anonymize individuals, discounting personal interpretations of social norms. Other books focus on extreme cases—the counter-cultural young with their tattoos, the economic elite with their enthusiasm for high fashion. It is my aim to provide a study of the clothing choices made by ordinary people, in keeping with the theoretical premises of my discipline, folklore, which, to begin, I will define as the study of creativity in everyday life.2

I call the realm of my concern “body art,” intending to denote all aesthetic modifications and supplementations to the body.3 My interest in the forms, functions, and meanings of dress and adornment, and especially in the choices individuals make within a web of social constraints, led me to India, an optimal locale for analysis. Decoration abounds; people lavish ornamentation on a wide variety of objects—temples, altars, vehicles, animals, and, especially, themselves. Adornment heightens beauty and wraps the bodies of gods and human beings with auspiciousness. Dress and adornment play a critical role in communication; they are symbolically integral to the lives of Indian people.

The cultural significance of adornment is reflected in language. In Hindi, the word shringar denotes self-adornment, but it can also mean beauty, express romantic or erotic love, as well as naming the most important of the nine Sanskrit rasas, which are, in the words of the great art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy, “the substance of aesthetic experience.”4 The noun suhag is used to name the happy state of a woman whose husband is alive. It means as well the chest that holds her marital ornaments and makeup, and it implies a divine blessing to the one who has not lost the right to ornament herself, as widows have. Vidhu Chaturvedi told me that the word for husband, sajan, may have its roots in the word saj—embellishment, decoration—because a woman, by acquiring a husband, enters the stage of her life when she is officially encouraged to be ornamented and decorated. Hindi contains almost one hundred different terms for all the varieties of ornaments, defined by shape, size, and location on the body.5

Because the majority of the women are so attentively dressed and ornamented, India is a rich territory for mapping the field of choice in the realm of body art. While exploring this conspicuous and visually accessible terrain, I will aim to extract general principles of production, commerce, and adornment that may be applied subsequently in studies of subtler expressions of clothing and jewelry conducted elsewhere, among other populations. One of the advantages of studying body art, especially in a crowded, extravagantly adorned country like India, is the ease with which you can create a visual databank of thousands of examples, since these fill the streets, everywhere you go. Unlike other kinds of artistic expression that are difficult to access, such as furniture or folktales, the spectrum of adornment options—like the varieties of local architecture—are readily available to sight; they can be scrutinized and stored in the mind’s eye for retrieval.

The immense diversity of India, owing to the multiplicity of regional and religious cultures, is expressed visually through clothes and ornaments, making instant identification possible. The Hindu concept of darshan, of sacred sight, provides a precedent for all nonverbal communication, and helps to shape India’s notable orientation to the visual. A religious orientation helps to explain not only the cultural significance of vision, but also the importance of ornamentation. In many parts of India, shaping the body of the deity out of clay or stone is only the first step in an artistic process that culminates in the painting, dressing, and repetitive ritual adornment of the divine. Religious devotion, whether in temples by pundits or in homes by ordinary people, involves bathing, clothing, dressing, and decorating the body of the god—acts that attest to the power of adornment as communication. Since people who are highly religious tend to be more symbolically oriented, a study of signs and symbolic communication through bodily attire becomes particularly relevant in India, allowing, again, for a clear detection of patterns that might be more obscure in other cultural settings.

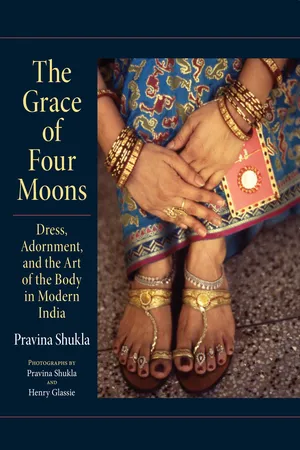

Aarti for Lord Shiva, Dashaswamedh Ghat, Banaras

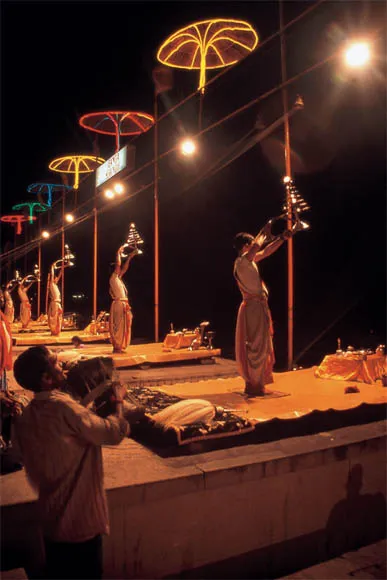

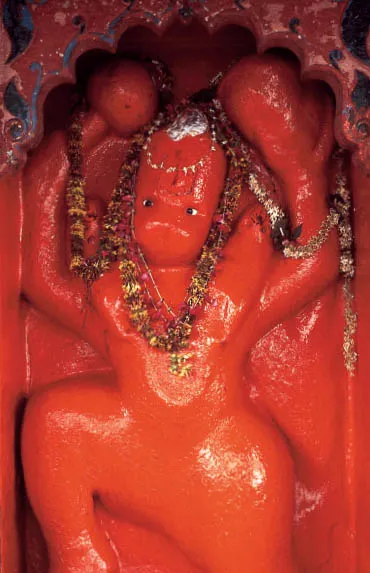

Deities in the streets, Banaras

Ganesh

Devi

Hanuman

Shahid at the Jacquard loom, Sonarpura, Banaras

Gold-brocaded Banarasi saris

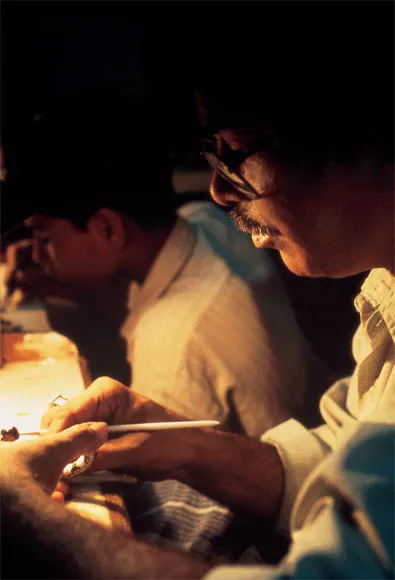

Gopal Prashad Meenekar with his son, Kush Kumar Seth, enameling jewelry

The front of the necklace with diamonds in the kundan setting

Kundan necklace made in Banaras

The back of the necklace with pink enameling

Bangles for sale, Banaras

Dashaswamedh Road

Shopping

Vishvanath Gali

Swati and Shachikant

Hindu Marriage

Namita performing aarti for her groom

The bride Namita on her wedding day

The bride Shalini’s hands on her wedding day

The bride Namita’s hands on her wedding day

Nina Khanchandani

Neelam Chaturvedi

Mukta Tripathi

The chaos of Chauk

Just as the specific forms and interpretations of Hinduism vary throughout the country, appearing in slightly modified form within a community and even within a single family, clothing norms likewise unfold within a wide and subtle range. It is this complexity and multiplicity of expression that makes India such an interesting place to study body art and the culture of clothing. Members of different populations dress distinctly—religious affiliation, for example, is readily identified by the clothing of men and especially of women—but a deeper analysis reveals a stunning array of variation within the general tradition of each of the major religious, social, caste, and economic groups found in the country. It is precisely this cultural tendency to divide and separate that Mahatma Gandhi tried to eradicate during his attempt to unite India against the British, when he worked toward liberation through the symbolic and economic significance of cloth and clothing.

A desire to showcase social difference is one of the universal goals of dressing, and this social function is especially obvious in a place of elaborate distinctions like India, where the caste system remains a profound part of daily life. In adorning themselves, people in India communicate religion, caste, and region—and they communicate fashionability and good taste. Some prosperous women told me they abandoned a particular fashion as soon as the maid or “Mrs. Rickshawwallah” started wearing it, erasing the socioeconomic division between servants and those “advanced” people of the higher classes.

The religious importance of seeing and adornment, and the importance of adornment as a marker of identity in a society divided by religious persuasion, caste, and social class—these reasons make India a powerful site for ethnographic investigation of body art. Another reason is found in the richness of opportunities for personal expression. Most items of adornment are still handmade. Every step of jewelry production requires the deft craft of the hand. Textiles are stamped, tie-dyed, and embroidered, while saris are laboriously handwoven. Though many clothes are readymade and bought off the rack, a considerable amount of hand-tailoring allows for creativity on the part of the customers who order clothes that reflect their aesthetic visions, and on the part of the tailors who respond to those visions. Custom-ordered clothes and jewelry allow greater leeway for expression among both producers and consumers than those ground out in a factory; choice in machine-made goods is confined to the act of purchase. Finally, creativity in assemblage is wide and deep for women in India because of the great number of variables in body art—including both the “compulsory” items that must be worn by married women (on the forehead, neck, ears, nose, fingers, wrists, ankles, and toes) and the wide range of options that remain open to free choice.

I chose to situate this study in the ancient city of Banaras, officially known as Varanasi, but still called “Banaras” by its people. My choice involved both personal and intellectual reasons. My parents are both from Banaras, and I have visited the city throughout my life. For me, the experience of India has always been the experience of Banaras. One of my most vivid memories of India involves a beloved item of body art: a pair of denim sandals, embroidered with a red flower, which I was given in Brazil, where we lived at the time. One day, when I was five or six, I was walking through the crowded galis of Banaras, distracted by the colorful toys hawked by the street vendors, when I accidentally stepped into a deep pile of dung left by one of the cows that wander the lanes. Horrified, I reached down and daintily unbuckled the clasp, lifting my small foot out, leaving the marvelous sandal behind on the street. Then, stubbornly, I hopped on one foot the whole way home, back to my Nanaji’s grand old house that was lost inside the maze of narrow alleys. The sacrificed sandal holds many of my feelings toward Banaras: attraction, revulsion, and resilience despite difficulty.

At the end of that visit to India, my older sister and I bought ourselves little aluminum suitcases, which we hoped would impress our classmates back in Brazil. We carried those shiny suitcases proudly to school, and caused so much laughter among the other kids that we came home, put the suitcases away, and never touched them again. Our humiliation taught me a lesson that I would return to as an adult: body art (which includes fashionable accessories) lives in a cultural context, and it rarely transcends local aesthetic norms.

My parents are Indian, yet I was born in Oslo, Norway, and grew up in São Paulo, Brazil, where I lived with my parents and two sisters, Divya and Bobby, until I was a teenager. We grew up speaking Hindi at home, Portuguese in the streets, and we attempted to master English when we arrived in the United States. In Brazil, our social circle turned within the Indian community; we went to weekly dinner parties where people spoke Hindi and ate Indian food, and where the women, though living in South America, wore colorful saris as an assertion of communal identity and personal pride.

India

Personal and familial connections to Banaras made it the logical place for me to begin my study of all the aspects of body art: production, marketing, purchase, and personal adornment. This book is by no means an ethnographic portrait of Banaras. I use the city as the backdrop against which to analyze the complex artistic processes of bodily adornment. Banaras is the main pilgrimage site for Hindus—they call it the “Hindu Mecca.” This is because Lord Shiva, locally known as Vishvanath—The Lord of the Universe—rules the world from Banaras, from Kashi, the City of Light. Pilgrims add to the city’s population of one million as many as two hundred thousand people a day.6 They come from all over the country and throughout the world of the Indian diaspora to take darshan of Vishvanath at the Golden Temple and to bathe in the sacred Ganges. Several times I have been told that if you had a one hundred kilo sack of rice, and put one grain in each of the temples of Banaras, you would run out of rice before you ran out of temples—such is the religious richness of the place.

Banaras is a place for prayer, and it is a place for death. The old, infirm, and widowed come here to die, since the one who dies here escapes the cycles of rebirth, avoiding another lifetime in this miserable world. Processions of relatives carrying wrapped dead bodies can be seen or heard throughout the day, every day, in the old part of the city, where the stores sell clothes and bangles, and the workshops produce saris and jewelry. Advancing aggressively, relentlessly, toward the river where the body will be cremated and the ashes set adrift, the bearers of the corpses chant “Ram nam satya hei”: Ram’s name is truth; the only truth is Ram, all else is illusion, maya.

The throngs of pilgrims, grieving relatives, and tourists—tourists more native than foreign—make for a festival-like atmosphere. The streets are eternally crowded, thick with vendors and pilgrims and cows, loud with constant invitations to visit shops, give alms, or take a boat ride...