eBook - ePub

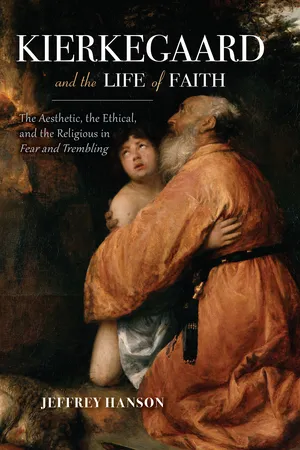

Kierkegaard and the Life of Faith

The Aesthetic, the Ethical, and the Religious in Fear and Trembling

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kierkegaard and the Life of Faith

The Aesthetic, the Ethical, and the Religious in Fear and Trembling

About this book

"A thorough, considered, and provocative treatment of what justifiably remains Kierkegaard's most famous book." —

Marginalia Review of Books

Soren Kierkegaard's masterful work Fear and Trembling interrogates the story of Abraham and Isaac, finding there one of the most profound and critical dilemmas in all of religious philosophy. While several commentaries and critical editions exist, Jeffrey Hanson offers a distinctive approach to this crucial text.

Hanson gives equal weight to all three of Kierkegaard's "problems," dealing with Fear and Trembling as part of the entire corpus of Kierkegaard's thought and putting all parts into relation with each other. Additionally, he offers a distinctive analysis of the Abraham story and other biblical texts, giving particular attention to questions of poetics, language, and philosophy, especially as each relates to the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious.

Presented in a thoughtful and fresh manner, Hanson's claims are original and edifying. This new reading of Kierkegaard will stimulate fruitful dialogue on well-traveled philosophical ground.

Soren Kierkegaard's masterful work Fear and Trembling interrogates the story of Abraham and Isaac, finding there one of the most profound and critical dilemmas in all of religious philosophy. While several commentaries and critical editions exist, Jeffrey Hanson offers a distinctive approach to this crucial text.

Hanson gives equal weight to all three of Kierkegaard's "problems," dealing with Fear and Trembling as part of the entire corpus of Kierkegaard's thought and putting all parts into relation with each other. Additionally, he offers a distinctive analysis of the Abraham story and other biblical texts, giving particular attention to questions of poetics, language, and philosophy, especially as each relates to the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious.

Presented in a thoughtful and fresh manner, Hanson's claims are original and edifying. This new reading of Kierkegaard will stimulate fruitful dialogue on well-traveled philosophical ground.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kierkegaard and the Life of Faith by Jeffrey Hanson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Titular Matters

IT IS NO secret that the title “Fear and Trembling” comes from the letter of Saint Paul to the Philippians, chapter 2, verse 12. It is clearly meant to capture the pervasive mood of the text, as Kierkegaard himself approvingly noted in the review of it that was penned by Bishop Mynster. In that review, Mynster asked the question, “But why is that work called Fear and Trembling? Because its author has vividly comprehended, has deeply felt, has expressed with the full power of language the horror that must grip a person’s soul when he is confronted by a task whose demands he dare not evade, and when his understanding is yet unable to disperse the appearance with its demand that seems to call him out from the eternal order to which every human being shall submit.”1 In The Point of View for My Work as an Author, Kierkegaard wrote that he had been pleased to find that Mynster’s remarks found the proper emphasis.2 So clearly part of the reason Kierkegaard chose this title was to create an atmospheric effect in the mind of the reader. It is meant to summon a mood of seriousness, of anxiety in the face of being called to an exceptional task, a task that cannot be explained in traditional philosophical terms. An examination of the chapter from Paul reveals other clear associations that also pervade the text. The context of verse 12—which reads, “Wherefore, my beloved, as ye have always obeyed, not as in my presence only, but now much more in my absence, work out your own salvation with fear and trembling”—is immediately following one of the more important passages in Scripture for kenotic theological speculation,3 which is itself situated before and after exhortations by Paul to the distinctive moral life that the Philippian faithful should be living out. He calls them to have “the same love, being of one accord, of one mind”;4 he instructs them to “let nothing be done through strife or vainglory; but in lowliness of mind let each esteem other better than themselves”;5 and he encourages them to “look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others.”6 These moral directions find their justification in the kenotic passage; the Philippian believers are to act this way in order to model the mind of Christ: “Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus: Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God: But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross.”7

The Philippians, then, are to be as Christ was; they are to imitate his humility, his adoption of a life of service, and his obedience to the Father, even if that obedience means submitting to the worst kind of death. Having done all this, Christ is exalted by God the Father and is given the name that is above all names.8 Thereafter, in verse 12 Paul instructs his hearers to work out their own salvation in imitation of Christ’s kenotic self-emptying and (one presumes) in anticipation of sharing in his rewards. Less often noticed is the subsequent verse, which reads, “For it is God which worketh in you both to will and to do of his good pleasure.”9 The faithful are to work out their salvation in fear and trembling because it is God who is working in them. The reference to Paul can be understood quite straightforwardly as a preliminary intimation of the text’s intent to lay the foundation for a “second ethics,” to suggest how the ethical ideal can be rejected and rereceived in altered fashion as a component of the life of faith.10

The theme of Philippians 2 is one that is forever in the background of Fear and Trembling; as Christ emptied himself radically, so must the faithful believer empty herself and adopt a wholly transformed style of life, one inclusive of obedience to the will of the Father, humility, service to others, unity, and the setting aside of all self-interest and rivalry. Without making too much, then, of the connection between the content of Fear and Trembling and Philippians 2 we can easily say that they both take as their concern the morally significant ways in which the believer’s life ought to be transformed by her faith. The believer is exhorted by both Paul and Kierkegaard to be conscious of the reality that it is God who works in her life to effectuate her conformity to Christ’s moral model and that this work is done by God to capacitate her knowledge of, and ability to execute, his will. So not only is the particular verse an appropriate choice with respect to the atmosphere or mood of the text as a whole, so also the chapter’s larger theme is one that echoes with the text’s content as a whole.

The subtitle to Fear and Trembling, “Dialectical Lyric,” has posed a challenge for commentators if only because no one knows what to make of it. It seems fairly obvious that Kierkegaard meant to refer to the form of the work, which he was elsewhere perfectly content to call “aesthetic,”11 so clearly there is no conflict between the designation of “aesthetic” and the designation of “dialectical lyric”; and it seems equally obvious that the form of the work is meant to combine two seemingly incongruous genre descriptors. “Dialectic” suggests the methodical rigor of modernist discursive reason, while “lyric” suggests the stylistic elegance of poetry or song. It is undeniably the case that Kierkegaard intended that the work innovate in terms of its form, that it partake of philosophical rigor and beauty in expression, but much more than that is difficult to say, especially (and this may be the most salient point to note about the subtitle) since Kierkegaard never again had recourse to the term “dialectical lyric” and did not use it again in his published writings.12

Certainly the term “lyric” in the subtitle has contributed to a common way of understanding who the text’s author, Johannes de Silentio, is—namely, as a poet. Yet I wish to complicate matters because Silentio’s status as a poet in a straightforward sense is far from clear, and calling him a poet leads to the dubious implication that his work is of a piece with the project of idealization, which is not his agenda at all but is part and parcel of resignation and the dead-end of unreconstructed aestheticizing. As scholars of this text know, on the original title page drafted for Fear and Trembling, Johannes de Silentio was billed as “a poetic person who exists only among poets.”13 And scholars further know that Silentio denies that he is a philosopher.14 The combination of the two observations, as well as the lengthy meditation on the relationship between the poet and the hero found in the “Eulogy on Abraham,” has led many to characterize Silentio as a poet; however, this is a highly problematic attribution for three reasons, in escalating order of importance.

First, Kierkegaard withdrew the original characterization of Silentio as a poetic person existing only among poets and presumably did so for a reason. The deliberate nature of this exclusion is underscored by the one-time presence in the preface of a description of Silentio as a “formerly poetic person.”15 Second, there is no real reason to identify Silentio with the poet spoken of in the “Eulogy”; this has been repeatedly done because one could construe a parallelism between what Silentio says there and what he is currently undertaking in the text before us, but that Silentio thinks of himself as a poet or as “the poet” of the “Eulogy” remains an unwarranted assumption. This is especially so in view of the third reason, which is that every time Silentio introduces an illustrative narrative in the third Problema section he explicitly dissociates his use of the narrative vignette from poetic usage and always distinguishes between his own use of the narrative and the use that would be made of it by “poets.”

This final observation will be developed at greater length in the chapter on Problema III, but suffice it say for now that I do not take the view that Silentio can be unproblematically viewed as a poet; in point of fact it is quite clear that he always distances himself from “the poets.”16 This distancing was always part of the original plan for the text, as an outline of Fear and Trembling from the journals reveals. There Kierkegaard wrote, “If the present age had a poet he would be able to relate what these two men (Abraham and Isaac) talked about along the way,” and again he asks, “Where indeed is the contemporary poet who has intimations of such conflicts? And yet Abraham’s conduct was genuinely poetic, noble, more noble than anything I have read in tragedies.”17 So even in germ, Fear and Trembling was intended to be “poetic” in a different, more genuine vein. It must first be taken into account that Silentio more often speaks of himself as not a poet than as one, and then, in the course of this work, I will develop a richer account of what sort of poetics Silentio is engaged in. To anticipate, let me point out that a clue is provided by Kierkegaard himself in an 1849 journal entry:

I understood myself to be what I must call a poet of the religious, not however that my personal life should express the opposite—no, I strive continually, but that I am a “poet” expresses that I do not confuse myself with the ideal.

My task was to cast Christianity into reflection, not poetically to idealize (for the essentially Christian, after all, is itself the ideal) but with poetic fervor to present the total ideality at its most ideal—always ending with: I am not that, but I strive. If the latter does not prove correct and is not true about me, then everything is cast in intellectual form and falls short.18

Silentio could arguably be understood as a poet in the same sense that Kierkegaard thought of himself as a poet; in this connection, “poet” signifies principally one who recognizes oneself as not realizing the ideal. For Kierkegaard the man, writing in his journal, to be a poet means to recognize that one is not the ideal but that one strives for it. This part perhaps is not perfectly analogous, inasmuch as Silentio may not be actually striving for faith, but he does respect it and even is sometimes clearly impressed, not to say shattered, by it. But the comparison still holds for two principal reasons.

First, Silentio, like Kierkegaard himself, could be said to “cast Christianity into reflection.” This is not the same as pretending to comprehend Christianity philosophically, something Silentio argues cannot be done.19 It is to “shed light” indirectly or set off the phenomenon in question negatively, by contrast with what it is not, and this Silentio does quite frequently. Again in the journal, Kierkegaard says plainly of this pseudonym: “Johannes de Silentio has never claimed to be a believer; just the opposite, he has explained that he is not a believer—in order to illuminate faith negatively.”20 It is quite clear from the text itself that Silentio is not a faithful person, and so from him we get an “outsider’s perspective.” There is in this some good to be had surely, as outsiders often see more clearly than insiders, but readers of Fear and Trembling also should be on guard against potential distortions in the account. It is my view that these are few and far between, and I will remark on them as they come up, but for the most part Silentio reports on faith accurately and sympathetically and only sometimes imperfectly, owing to his inability to know what only the faithful themselves could know.21 In one of his unpublished replies to Theophilus Nicolaus, Kierkegaard clarified Silentio’s strategy as an effort “merely to illuminate Abraham, not to explain Abraham directly, for after all he cannot understand Abraham.”22 Once again, this seems to speak to a distinction in Kierkegaard’s mind between explaining the phenomenon at hand directly and indirectly casting light upon it, which seems to have been the aim of both his own authorial project and the small part of it that he attributed to Silentio.

Second, both Kierkegaard himself as an author and Silentio could be said to be at a remove from poetically idealizing; this too is distinguishable from what they are doing as writers and is not the same as casting into reflection. Kierkegaard writes in the entry above that the reason he is not poetically idealizing is because “the essentially Christian, after all, is itself the ideal.” This is in fact another reason to question whether Silentio can be called a poet. An extremely important journal entry speaks on the connection between the poet and idealizing in these words: “What does it mean to poetize? It means to contribute ideality. The poet takes an actuality which lacks something of ideality and adds to it, and this is the poem.”23 So if the poet is principally one who takes from actuality and idealizes it in order to create his poem, neither Kierkegaard nor Silentio can be a poet in the conventional sense because for both of them the actuality they take up in their examinations, the actuality they attempt to cast into reflection, is itself already the ideal. Kierkegaard calls himself a poet of the religious and says that he cannot be a straightforward poet, however, because the essentially Christian is already ideal. In the same journal entry, Kierkegaard ridicules Adam Oehlenschläger’s attempt to poetize Socrates, because Socrates is already the ideal and cannot be poetized. The very attempt of a poet to idealize what is already actually ideal renders the poet a “laughingstock.”24 In much the same way, Silentio aims to shed light on Abraham, but if Abraham is the true ideal of faith, then Abraham cannot be poetized any more than Socrates could be poetized. This must be kept in mind, particularly when reading the “Eulogy on Abraham” and particularly in order to keep an appropriate separation in place between Silentio’s project and that of a conventional poet. It is of course true that like Kierkegaard himself Silentio brings “poetic fervor” to his work, but this does not make him a poet in a straightforward sense.

The obvious reference in the pseudonymous author of this text’s name to silence must also be accounted for briefly here.25 The irony of our author’s loquaciousness on faith and its apparent contrast to his own name has been noted, but fortunately there is not much in the way of mystery here with respect to the nature of silence. We have a clear sense of what Kierkegaard intended on this score from two sources: first, his own writing in the journal and Point of View, and, second, content internal to the text itself.

First, if we turn to Point of View, from the same passage where Kierkegaard hailed with approval Mynster’s reaction to Fear and Trembling, we find these words: “I had made up my mind that I was a religious author whose concern is with the single individual, an idea (the single individual versus the public) in which a whole life- and worldview is concentrated. From now on, that is, as early as Fear and Trembling, the earnest observer who himself has religious presuppositions at his disposal, the earnest observer to whom one can make oneself understood at a distance and to whom one can speak in silence (the pseudonym: Johannes—de Silentio)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Titular Matters

- 2 A Philosophical Preface

- 3 A Narrative Approach

- 4 A Rhetorical Rehearsal

- 5 Beginning from the Heart

- 6 Teleological Suspensions

- 7 Absolute Duty

- 8 Silence and Speech

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index