![]()

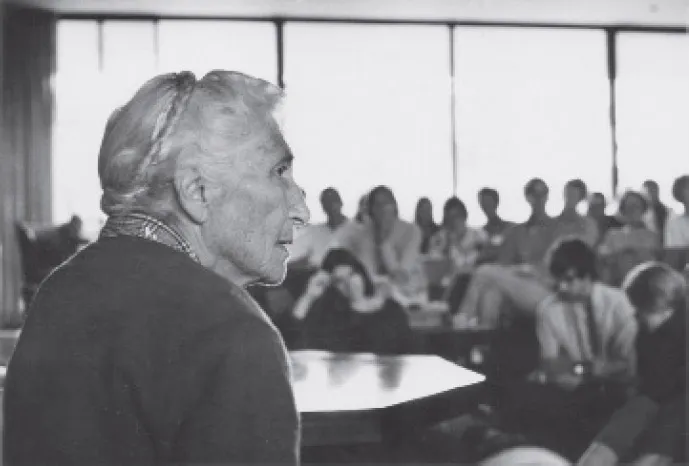

Frances Flaherty circa 1968. Photo courtesy of International Film Seminars, Inc./The Flaherty, New York.

1

THE FLAHERTY WAY

The Flaherty Seminar is one of the oldest, continuously running gatherings for independent film in the world. Launched by Frances Flaherty in 1955, the seminar explored the “Flaherty Way” of making films, rejecting planning and scripts required by commercial production practices. Frances was the widow of renowned documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty. Although Robert directed the films and occupies a central, if controversial, place in documentary film history books, it was Frances who developed the Robert Flaherty Film Seminar for community, debate, dialogue, and screenings. The seminar has provided a retreat-like, closed setting for distributors, film librarians, filmmakers, funders, programmers, and scholars for more than sixty years.

Robert Flaherty, who shot films in exotic locations such as the Canadian north and Samoa and then shared production stories to eager acolytes rather than theorizing his practice, did not conceptualize the “Flaherty Way.” Instead, his widow developed the “Flaherty Way” after his death. She advocated for a poetic cinema that surrendered to the materials and the environment. In Frances’s vision, the “Flaherty Way” offered a more artisanal, personal cinema than the formulaic, predictable industrial model based on imposition of commercial norms, planning, and scripts. Resolutely anti-Hollywood, the “Flaherty Way” combined the explorer’s journeys into the unknown, the ethnographer’s observation of cultural patterns, and the Zen mystics’ openness to surroundings.

The Robert Flaherty Foundation and the Robert Flaherty Seminar emerged from Frances’s contention that learning to see in deeper, more complex ways could be acquired through intensive viewing and vigorous discussion. In a 1961 letter to the Guggenheim Foundation in support of a grant application by Frances, George Amberg wrote: “It may be useful to point out that Mrs. Flaherty is not, as would be natural, so much concerned with building a monument in honor of a great filmmaker and a great man, than with promoting and supporting a vital succession, establishing a tradition, making discoveries, and encouraging new talent. Toward this end, she organized the Flaherty Foundation and initiated the Flaherty Seminars, an annual venture devoted to the scholarly and critical study of the motion picture.”1

The Flaherty Foundation and the Flaherty Seminar are significant in film history. They show the challenges of the early foundational period in the development of the nascent nonprofit public media sector in the United States in the post–World War II period. They suggest the importance of institutional histories to delineate the infrastructure bolstering cinematic cultures beyond the commercial systems. The foundation and the seminars occupy a vital interstitial zone between emergent alternative film cultures in the 1950s: 16mm exhibition, art cinemas, educational and industrial films, film festivals, film societies, independent cinema beyond commercial studios, and university film education.

The Flaherty Foundation, formed by Frances and David Flaherty, Robert’s brother, in 1951, and its outgrowth, the Flaherty Seminar, inaugurated in 1955, were initially dedicated to preserving and circulating Flaherty’s films. They advocated for an artisanal, independent, poetic cinema immunized from the commercial Hollywood system. Convening a small, intimate group of distributors, editors, filmmakers, scholars, and writers on the family farm in Dummerston, Vermont, for ten days in the summer, the early years of the seminar were characterized by camaraderie, intellectual and artistic intensity, and a hope that cinema go beyond commercial filmmaking with its rules and conventions.

The early seminars focused on the works and practices of Robert Flaherty. Seminarians dived into close analysis of Flaherty films, such as Nanook of the North (1922) and Louisiana Story (1948), listened to lectures by those who worked on Flaherty films, such as Ricky Leacock and Helen van Dongen, and watched experimental and documentary films produced outside the Hollywood system.

Combining the ciné-club and film society models of postscreening discussion and more intellectual models of lectures elaborating cinematic techniques, the seminar did not operate as a film festival, with public screenings of narrative films in theaters. Instead, the Flaherty Seminar was a small gathering on the family farm, seminarians applied to attend, and many films were historical rather than current releases. The seminar advanced cinematic practice and conceptual thinking in the loosely defined nontheatrical sector. The early seminars’ emphasis on critical viewing, philosophical inquiry, and probing discussion distinguished it from film festivals. Its purpose was educational. It advocated for cinema as an art. Attendees were not an audience but were called participants, implying active engagement rather than passive viewing. As David Flaherty noted in 1960 after mounting five seminars on the Flaherty farm, “Yes, we think ‘participants’ is a better word to use than ‘students.’”2

The Flaherty Seminar emerged in the postwar context of the Cold War (1947–91), where the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense global military and strategic conflict between competing ideologies of democracy and communism. David Flaherty’s use of the word participant rather than student aligns with a Cold War ideology promulgating that the United States offered individual freedoms, in contrast to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which was figured as limiting freedom of expression and participation. The Cold War spurred US military buildup, a strategy of containment against the advances of communism around the globe, and the development and expansion of the United States Information Agency, a government organization to promote American culture through public diplomacy.3 The connection between US Cold War international strategies and practices and the Flaherty Seminar is not one of direct causation as much as it is one of a discursive historical surround that illuminates interpretation of how to position its politics and practices. The seminar occupied a complicated, somewhat foggy middle ground between the individualism promoted by US Cold War ideology and the communist collectivity of the USSR: it advanced auteurs and their individual artistic vision while it fostered an intense, yet isolated, group experience.

The Flaherty Seminar never openly aligned with entertainment and news industry unions, which had been under scrutiny and attack during the various post–World War II Red Scares. In 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) attacked Hollywood—almost 100 percent unionized by the postwar period—as a bastion of un-American activities. As historian Reynold Humphries contends, the red-baiting right identified Hollywood, with many of its union members supporting the antifascists in Spain and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, as communists. The Hollywood Ten included Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornits, Robert Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo, all of whom refused to cooperate and denounced the hearings as violations of their civil rights.4

America’s postwar economic success was tied to commercial narrative Hollywood films, which sold the American way of life as consumption.5 The 1947 HUAC hearings investigated screenwriters and directors from the film industry. According to Lary May, Hollywood embodied “moral experiment, cultural mixing, a militant labor movement, and middle class activism,” all attributes antithetical to the promulgation of the so-called American way of consumerist monopoly capital. The pro-HUAC entertainment industry members “sought to make Hollywood a model of an unprecedented American identity rooted in consensus and consumption.”6 With its East Coast location, the Flaherty Foundation and the Flaherty Seminar were geographically distant, operating in the milieu of independent, educational, documentary, experimental, and scientific filmmakers who were not unionized and worked outside of mass culture and Hollywood. However, the foundation and seminars were never identified with media industries, unions, or pro-communist ideologies. Instead, the Flaherty Seminar proffered a concoction of art, individualism, and some critical analysis, mostly from scholars. Whether conscious or not, these inclinations insulated the seminar from ideological attacks. For example, Erik Barnouw was a key figure in the early seminars. He had worked as a radio writer in New York for CBS and NBC. By 1957, he was elected chair of the Writers Guild of America East. In his scholarly histories of broadcasting written later in the 1966, he analyzed how the Red Scare produced caution and cowardice in television.7

The formation of the Flaherty Foundation and the Flaherty Seminar unfolded in the context of the Truman and Eisenhower presidencies, which intensified the Cold War through military buildup and propaganda. This postwar period witnessed the advancement of expanding consumption, an ideology of consensus, and a suburban domestic revival motored by what historian Warren Sussman dubbed “unprecedented economic growth unfolding after World War II” in the context of affluence and familialism.8 Frances and David Flaherty channeled this larger discourse of familialism, situating the foundation and the seminar not as a union of independent filmmakers but instead as a family gathering, resonating with dominant domesticating ideologies of the period.

However, the Cold War in the 1950s was not so simply the smooth production of consensus, consumerism, familialism, and homogeneity. It was also a period of social and cultural contradictions with the rise of African American blues, the Beats, the civil rights movement, and rock ’n’ roll—cultural movements that challenged conformity, familialism, and suburbia with cultural pluralism and political interventions.9 Besides showing George Stoney’s chronicle of an African American midwife in his sponsored public health film, All My Babies, the Flaherty seminar in the 1950s steered a less interventionist and directly confrontational course, positioning itself as an organization dedicated to retrieving cinema from commercial domains and rescuing it as an art.

This orientation toward salvaging cinema as an art form of personal expression aligned more easily with the larger Cold War artistic contexts of abstract expressionism in painting and the New Criticism in literature. As Erika Doss has argued, in the postwar period, abstract expressionism—epitomized in action painter Jackson Pollack—mobilized a concept of individual, apolitical gestural freedom that rendered it a “weapon against totalitarianism.” Both the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the US State Department, which sent exhibitions of this style overseas to promote freedom against the strictures of the USSR’s socialist realism, heralded abstract expressionism.10 Although Frances’s writings and Flaherty seminar transcripts never mention abstract expressionism directly, their presentation of the films of Robert Flaherty resonated with similar ideologies of action-based gestures, freedom, and individualism disconnected from larger political and social issues. Even from the beginning, the Flaherty Seminar was deeply embedded with auteurism and individualism, positioning it more in alignment with Cold War ideas than with the collectivities the civil rights movement or unions. The early seminars’ emphasis on the formal elements and structures of the Flaherty films also paralleled the school of literary New Criticism, with its emphasis on close reading that figured the text as an aesthetic object outsi...