![]()

Some Monday for Sure

Nadine Gordimer

MY SISTER’S HUSBAND, Josias, used to work on the railways but then he got this job where they make dynamite for the mines. He was the one who sits out on that little iron seat clamped to the back of the big red truck, with a red flag in his hand. The idea is that if you drive up too near the truck or look as if you’re going to crash into it, he waves the flag to warn you off. You’ve seen those trucks often on the Main Reef Road between Johannesburg and the mining towns—they carry the stuff and have DANGER-EXPLOSIVES painted on them. The man sits there, with the iron chain looped across his little seat to keep him from being thrown into the road, and he clutches his flag like a kid with his balloon. That’s how Josias was, too. Of course, if you didn’t take any notice of the warning and went on and crashed into the truck, he would be the first to be blown to high heaven and hell, but he always just sits there, this chap, as if he has no idea when he was born or that he might not die on a bed an old man of eighty. As if the dust in his eyes and the racket of the truck are going to last for ever.

I don’t think it ever came into her head that any day, every day, he could be blown up instead of coming home in the evening.

My sister knew she had a good man but she never said anything about being afraid of this job. She only grumbled in winter, when he was stuck out there in the cold and used to get a cough (she’s a nurse), and on those times in summer when it rained all day and she said he would land up with rheumatism, crippled, and then who would give him work? The dynamite people? I don’t think it ever came into her head that any day, every day, he could be blown up instead of coming home in the evening. Anyway, you wouldn’t have thought so by the way she took it when he told us what it was he was going to have to do.

I was working down at a garage in town, that time, at the petrol pumps, and I was eating before he came in because I was on night shift. Emma had the water ready for him and he had a wash without saying much, as usual, but then he didn’t speak when they sat down to eat, either, and when his fingers went into the mealie meal he seemed to forget what it was he was holding and not to be able to shape it into a mouthful. Emma must have thought he felt too dry to eat, because she got up and brought him a jam tin of the beer she had made for Saturday. He drank it and then sat back and looked from her to me, but she said, “Why don’t you eat?” and he began to, slowly. She said, “What’s the matter with you?” He got up and yawned and yawned, showing those brown chipped teeth that remind me of the big ape at the Johannesburg zoo that I saw once when I went with the school. He went into the other room of the house, where he and Emma slept, and he came back with his pipe. He filled it carefully, the way a poor man does; I saw, as soon as I went to work at the filling station, how the white men fill their pipes, stuffing the tobacco in, picking out any bits they don’t like the look of, shoving the tin half-shut back into the glove box of the car. “I’m going down to Sela’s place,” said Emma. “I can go with Willie on his way to work if you don’t want to come.”

We had Mandela and the rest of the leaders, cut out of the paper, hanging on the wall, but he had never known, personally, any of them.

“No. Not to-night. You stay here.” Josias always speaks like this, the short words of a schoolmaster or a boss-boy, but if you hear the way he says them, you know he is not really ordering you around at all, he is only asking you.

“No, I told her I’m coming,” Emma said, in the voice of a woman having her own way in a little thing.

“To-morrow.” Josias began to yawn again, looking at us with wet eyes. “Go to bed,” Emma said, “I won’t be late.”

“No, no, I want to . . .” he blew a sigh “—when he’s gone, man—” he moved his pipe at me. “I’ll tell you later.”

Emma laughed. “What can you tell that Willie can’t hear—” I’ve lived with them ever since they were married. Emma always was the one who looked after me, even before, when I was a little kid. It was true that whatever happened to us happened to us together. He looked at me; I suppose he saw that I was a man, now: I was in my blue overalls with Shell on the pocket and everything.

He said, “. . . they want me to do something . . . a job with the truck.”

Josias used to turn out regularly to political meetings and he took part in a few protests before everything went underground, but he had never been more than one of the crowd. We had Mandela and the rest of the leaders, cut out of the paper, hanging on the wall, but he had never known, personally, any of them. Of course there were his friends Ndhlovu and Seb Masinde who said they had gone underground and who occasionally came late at night for a meal or slept in my bed for a few hours.

“They want to stop the truck on the road . . .”

“Stop it?” Emma was like somebody stepping into cold dark water; with every word that was said she went deeper. “But how can you do it—when? Where will they do it?” She was wild, as if she must go out and prevent it all happening right then.

I felt that cold water of Emma’s rising round the belly because Emma and I often had the same feelings, but I caught also, in Josias’s not looking at me, a signal Emma couldn’t know. Something in me jumped at it like catching the swinging rope. “They want the stuff inside . . . ?”

I was scared of her. I don’t mean for what she would do to me if I got in her way, but for what might happen to her: something like taking a fit or screaming that none of us would be able to forget.

Nobody said anything.

I said, “What a lot of big bangs you could make with that, man” and then shut up before Josias needed to tell me to.

“So what’re you going to do?” Emma’s mouth stayed open after she had spoken, the lips pulled back.

“They’ll tell me everything. I just have to give them the best place on the road—that’ll be the Free State road, the others’re too busy . . . and . . . the time when we pass . . .”

“You’ll be dead.” Emma’s head was shuddering and her whole body shook; I’ve never seen anybody give up like that. He was dead already, she saw it with her eyes and she was kicking and screaming without knowing how to show it to him. She looked like she wanted to kill Josias herself, for being dead. “That’ll be the finish, for sure. He’s got a gun, the white man in front, hasn’t he, you told me. And the one with him? They’ll kill you. You’ll go to prison. They’ll take you to Pretoria gaol and hang you by the rope . . . yes, he’s got the gun, you told me, didn’t you . . . many times you told me . . .”

“The others’ve got guns too. How d’you think they can hold us up?—they’ve got guns and they’ll come all round him. It’s all worked out—”

“The one in front will shoot you, I know it, don’t tell me, I know what I say—” Emma went up and down and around till I thought she would push the walls down—they wouldn’t have needed much pushing, in that house in Tembekile Location—and I was scared of her. I don’t mean for what she would do to me if I got in her way, or to Josias, but for what might happen to her: something like taking a fit or screaming that none of us would be able to forget.

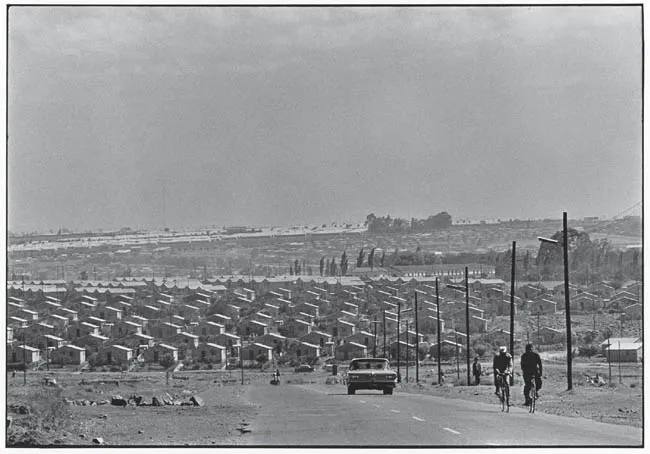

No known caption. Typical location has acres of identical four-room houses on nameless streets. Many are hours by train from city jobs. [Caption to a similar picture in House of Bondage.] Photo by Ernest Cole. Image taken between 1958 and 1966. Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation. © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

I don’t think Josias was sure about doing the job before but he wanted to do it now. “No shooting. Nobody will shoot me. Nobody will know that I know anything. Nobody will know I tell them anything. I’m held up just the same like the others! Same as the white man in front! Who can shoot me? They can shoot me for that?”

“Someone else can go, I don’t want it, do you hear? You will stay at home, I will say you are sick . . . you will be killed, they will shoot you . . . Josias, I’m telling you, I don’t want . . . I won’t . . .”

I was waiting my chance to speak all the time and I felt Josias was waiting to talk to someone who had caught the signal. I said quickly, while she went on and on, “But even on that road there are some cars?”

“Road-blocks” he said, looking at the floor. “They’ve got the signs, the ones you see when a road’s being dug up, and there’ll be some men with picks. After the truck goes through they’ll block the road so that any other cars turn off onto the old road there by Kalmansdrif. The same thing on the other side, two miles on. There where the farm road goes down to Nek Halt.”

“Hell, man! Did you have to pick what part of the road?”

“I know it like this yard.—Don’t I?”

Emma stood there, between the two of us, while we discussed the whole business. We didn’t have to worry about anyone hearing, not only because Emma kept the window wired up in that kitchen, but also because the yard the house was in was a real Tembekile Location one, full of babies yelling and people shouting, night and day, not to mention the transistors playing in the houses all round. Emma was looking at us all the time and out of the corner of my eye I could see her big front going up and down fast in the neck of her dress.

“. . . so they’re going to tie you up as well as the others?”

He drew on his pipe to answer me.

“Hell, it’s clever, ay?”

We thought for a moment and then grinned at each other; it was the first time for Josias, that whole evening.

Emma began collecting the dishes under our noses. She dragged the tin bath of hot water from the stove and washed up. “I said I’m taking my off on Wednesday. I suppose this is going to be next week.” Suddenly, yet talking as if carrying on where she let up, she was quite different.

“I don’t know.”

“Well, I have to know because I suppose I must be at home.”

“What must you be at home for?” said Josias.

“If the police come I don’t want them talking to him,” she said, looking at us both without wanting to see us.

“The police—” said Josias, and jerked his head to send them running, while I laughed, to show her.

“And I want to know what I must say.”

“What must you say? Why? They can get my statement from me when they find us tied up. In the night I’ll be back here myself.”

“Oh yes,” she said, scraping the mealie meal he hadn’t eaten back into the pot. She did everything as usual; she wanted to show us nothing was going to wait because of this big thing, she must wash the dishes and put ash on the fire. “You’ll be back, oh yes.—Are you going to sit here all night, Willie?—Oh yes, you’ll be back.”

And then, I think, for a moment Josias saw himself dead, too; he didn’t answer when I took my cap and said so long, from the door.

I knew it must be a Monday. I notice that women quite often don’t remember ordinary things like this, I don’t know what they think about—for instance, Emma didn’t catch on that it must be Monday, next Monday or the one after, some Monday for sure, because Monday was the day that we knew Josias went with the truck to the Free State Mines. It was Friday when he told us and all day Saturday I had a terrible feeling that it was going to be that Monday, and it would be all over before I could—what? I don’t know, man. I felt I must at least see where it was going to happen. Sunday I was off work and I took my bicycle and rode into town before there was even anybody in the streets and went to the big station and found that although there wasn’t a train on Sundays that would take me all the way, I could get one that would take me about thirty miles. I had to pay to put the bike in the luggage van as well as for my ticket, but I’d got my wages on Friday. I got off at the nearest halt to Kalmansdrif and then I asked people along the road the best way. It was a long ride, more than two hours. I came out on the main road from the sand road just at the turn-off Josias had told me about. It was just like he said: a tin sign “Kalmansdrif” pointing down the road I’d come from. And the nice blue tarred road, smooth, straight ahead: was I glad to get onto it!

She did everything as usual; she wanted to show us nothing was going to wait because of this big thing.

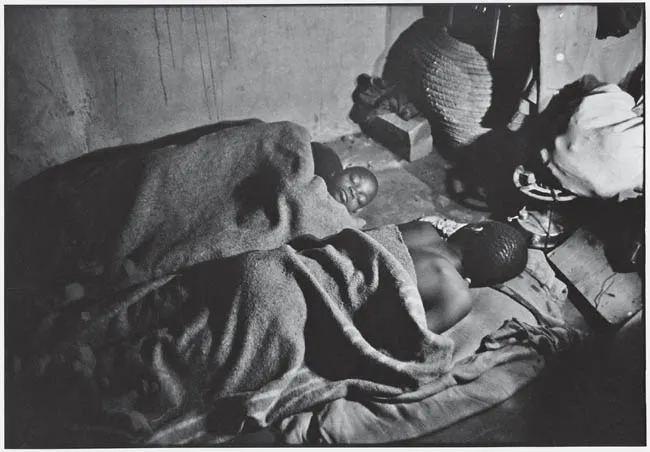

There is one bed in the Mogale house. Daniel and Martha and their two youngest sleep in it; others sleep on floor. [Caption from House of Bondage.] Photo by Ernest Cole. Image taken between 1958 and 1966. Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation. © The Ernest Cole Family Trust

I hadn’t taken much notice of the country so far, while I was sweating along, but from then on I woke up and saw everything. I’ve only got to think about it to see it again now. The veld is flat round about there, it was the end of winter, so the grass was dry. Quite far away and very far apart, there was a hill, and then another, sticking up in the middle of nothing, pinkish colour, and with its point cut off like the neck of a bottle. Ride and ride, these hills never got any nearer and there were none beside the road. It all looked empty and the sky much bigger than the ground, but there were some people there. It’s funny you don’t notice them like you do in town. All our people, of course; there were barbed wire fences, so it must have been white farmers’ land, but they’ve got the water and their houses are far off the road and you can usually see them only by the big dark trees that hide them. The people had mud houses and there would be three or four in the same place made bare by goats and people’s feet. Often the huts were near a kind of crack in the ground, where the little kids played and where, I suppose, in summer, there was water. Even now the women were managing to do washing in some places. I saw children run to the road to jig about and stamp when cars passed, but the men and women took no interest in what was up there. It was funny to think that I was just like them, now, men and women who are always busy inside themselves with jobs, plans, thinking about how to get money or how to talk to someone about something important, instead of like the children, as I used to be only a few years ago, taking in each small thing around them as it happens.

Still, there were people living pretty near the road. What would they do if they saw the dynamite truck held up and a fight going on? (I couldn’t think of it, then, in any other way except like I’d seen hold ups in Westerns, although I’ve seen plenty of fighting, all my life, among the Location gangs and drunks—I was ashamed not to be able to forget those kid-stuff Westerns at a time like this.) Would they go running away to the white farmer? Would somebody jump on a bike and go for the police? Or if there was no bike, what about a horse?—I saw someone riding a horse.

I rode slowly to the next turn-off, the one where a farm road goes down to Nek Halt. There it was, just like Josias said. Here was where the other road-block would be. But when he spoke about it there was n...