![]()

| CHAPTER ONE

Race Matters: The Evolution of Race Filmmaking |

[Instead of] a lot of slapstick, chicken-eating, watermelon Negro pictures like they had been making, … we made something that had never been made before … We were pioneers …

—George Johnson

Early race filmmaking is unquestionably the story of pioneers—pioneers like William D. Foster, the “Dean of Negro Motion Pictures,” who foresaw a dynamic future for blacks in the film industry; Emmett J. Scott, a Tuskegee Institute official who struggled valiantly to produce a film in response to D. W. Griffith’s vitriolic The Birth of a Nation; Noble and George Johnson, brothers and co-founders of the distinguished Lincoln Motion Picture Company, who produced high-quality pictures that promoted the ideology of race uplift; Robert Levy, the white founder of Reol Productions and the sponsor of the prestigious Lafayette Players, from whom many race filmmakers drew their casts; and Oscar Micheaux, the first black film auteur and the most prolific race producer of his day.1

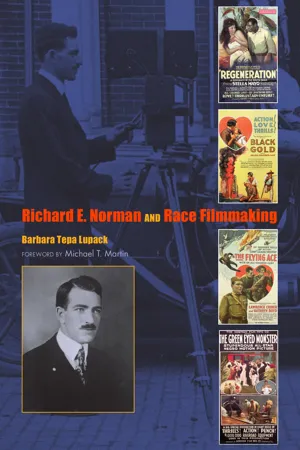

Early race filmmaking is also the story of another pioneer, Richard E. Norman, who—though less well-known today than many of his contemporaries—was no less accomplished. An innovative white filmmaker who began his career as a traveling producer of white-cast “home talent” pictures in the Midwest, Norman moved his operation to Florida, then the country’s moviemaking capital, in the late 1910s and began producing pictures for the underserved market of black filmgoers. The first and ultimately only independent race producer to own and operate his own studio, Norman released seven popular and successful feature films before the advent of sound pictures in the late 1920s forced him to curtail production. Those films were memorable not just for their thrilling plots and interesting locales but also for their casting of black actors in prominent, positive, and nonrestrictive roles.

Rather than just perpetuating crude and retrogressive representations, Norman and his fellow filmmakers determined to present realistic depictions of black Americans by creating an alternate set of cultural referents and establishing new black character types and situations, particularly those that reflected postwar social changes.2 As George Johnson observed, unlike white moviegoers, who had long “based their idea of a Negro on the Stepin Fetchit [character,] the Negro himself was tired of seeing that type of picture. He wanted to see himself as he really was.”3

Race films afforded that opportunity. An expression of group consciousness, they served as a source of pride for black viewers, who recognized them as products that were created by and for their community. By employing race consciousness and identification as cohesive and binding forces, those movies became “an articulation of self that challenged the dominant culture’s ordering of reality.”4 Of particular significance was the way in which they would be “counterhegemonic without symmetrically ‘countering’ white culture on every point; for their oppositionality, if it could be called that, was in the circumvention, in the way they produced images that didn’t go through white culture. Seen by blacks, largely unseen by whites, race movies featured an all-black world, a utopian vision of ‘all-black everything.’”5 And that is precisely why they were successful.

At first glance, the black-cast, black-oriented movies seemed to borrow the familiar genres of Hollywood films, from mysteries to Westerns. But, as film scholar Jane Gaines writes, race films in fact “emptied” those genres and “filled [them] with different issues and outcomes,” so that while they appeared to be turned inward in their consideration of black community problems and black aspiration, they were simultaneously running commentaries on the white world that remained off-screen.6 And even though race films did not, by any means, shatter the racial clichés or halt the negative imagery that dominated American film, they offered an alternative to those troubling depictions and challenged other movie producers to strive for more balanced racial and ethnic portrayals in their pictures—a clear response to the “call to duty” that publisher Lester Walton issued in the New York Age (September 18, 1920): “to present the Negro in a complimentary light, … to gladden our hearts and inspire us by presenting characters typifying the better element of Negroes.”7

Race pictures also served a significant social and cultural function by helping to define black identity in the transition to modern urban life. As Jacqueline Najuma Stewart notes in her definitive study Migrating to the Movies, the Great Migration of hundreds of thousands of blacks from the South not only increased social and economic opportunities in Northern cities before, during, and after World War I; it also influenced the development of cinema as a major institution, particularly in terms of “its representational strategies and its practices as a social sphere,” and allowed movies to play a crucial role in the process of modernization and urbanization of blacks. Whereas cinema’s early racial politics was evident in the racist portrayals on screen, segregation in theaters, and exclusion of blacks from the dominant sphere of production, the new films being produced for black audiences provided a major site in which black subjects could be seen in modern ways and in which “Black public spheres were constructed and interpreted, empowered and suppressed.”8

Yet even with the opening of movie houses in New York, Chicago, and throughout the North to accommodate the influx of migrating Southern blacks, the number of actual theaters where race films could be screened was small. Film pioneer William Foster reported that there were only “112 ‘colored’ theaters in the United States in 1909, with those outside major cities being mostly ‘five and ten cent theaters, vaudeville and moving pictures,’” and 214 serving a black clientele in 1913.9 Black filmmaker and Afro-American Film Company founder Hunter Haynes, in an article for the Indianapolis Freeman (March 14, 1914), pegged the number at “238 colored houses in the United States [catering exclusively to black patrons] as against 32,000 white houses” in 1914.10 Even in 1921–1922, peak years for race filmmakers, Richard E. Norman wrote that “scattered over twenty-eight states,” there were just 354 “Negro theatres” (only 121 of which he considered to be outlets for his films); and he noted that, by the end of 1922, some of those theaters had already closed.11 Moreover, those same black theaters typically showed more Hollywood films than independent ones, while white theaters, which had a much wider market, rarely booked independent race films at all.

The early race film producers had imagined that they could work toward racial uplift while turning a profit for themselves in a lucrative new industry. But they learned very quickly that they were at a significant disadvantage in terms of both financing and experience.12 Some discovered that, despite their good intentions, they would be unable to compete with the major studios and never even moved into production with their story ideas. Others made only a single film before they too folded their operations. Still others sought backing from white investors simply to survive.

Most independent race filmmakers operated under other handicaps as well. Unlike the better-funded studio producers, who employed distribution agencies to circulate their films and who therefore were able to keep their studios open and working on new productions, they had to distribute their films themselves, usually by roadshowing them from town to town. “We had to make a picture,” one early filmmaker recalled, “and then we had to close down everything and take the same man [actor] we made the picture with and go out and spend money traveling all over the United States, trying to get money enough to make another picture. But we were out of business all that time.”13

In addition to the scarce resources at their disposal and the tough competition from the dominant film industry, race filmmakers also had to struggle to satisfy their various constituencies. In particular, they had to address and accommodate the preferences of black filmgoers, especially urban filmgoers “with disposable income and race-conscious views,” by managing the contradictions that shaped the emerging black film culture, including “the politics of race stereotypy, the cinema’s high and low appeals to largely working-class audiences, and Black moviegoers’ increasingly sophisticated and diverse reconstructive viewing practices.” Yet by adapting or reworking mainstream conventions to emphasize racial achievement—by “inhabiting” and incorporating white genres rather than merely “imitating” white forms, to borrow Jane Gaines’s important distinction—those filmmakers were able to produce “city comedies, migration melodramas, and military newsreels that reflected and renewed assertions of American identity on the part of Black audiences.”14 Thus, despite the fact that virtually all early race films were underfinanced, poorly distributed, and technically inferior to the Hollywood product, they were, in themselves, remarkable social and cinematic achievements.

The first race filmmaker was William D. Foster, who recognized quite early the economic promise that the developing motion picture industry had to offer. While working in New York City for horseman Jack McDonald, he became interested in show business and took on the role of publicist for Bob Cole and Billy Johnson’s A Trip to Coontown Company and later for the landmark musical shows In Dahomey and Abyssinia, starring the legendary black comedy team of Bert Williams and George Walker.15 Attracted by the opening of Robert T. Mott’s Pekin Theatre, a black-managed and operated playhouse, in 1906, Foster moved to Chicago, where he became the Pekin’s business representative, a position that allowed him to view and book numerous black vaudeville acts. Under the pen name of Juli Jones, Foster also began writing articles on black show business for various race weeklies, including the Chicago Defender; and around 1910, he decided to enter the movie profession himself. After scraping together enough money to found the Foster Photoplay Company, he produced his first short, a two-reel comedy called The Railroad Porter (1912), now recognized as the first black-directed film, which had a strong opening in Chicago and was later shown in a few theaters in the East.

“One of the best informed men in theatricals hereabouts,” Foster predicted phenomenal success for race men with the “bravery and foresight” to wrestle with the problems of movie production and presentation.16 After all, “in a moving picture the Negro would off-set so many insults of the race—could tell their side of the birth of this great race.”17 To demonstrate his own bravery and foresight, Foster began investigating ways to establish himself in the industry. At one point he even headed to Florida, where Lubin, Pathé, Kalem, and other licensed film manufacturers were making movies, to evaluate the feasibility of building a studio there. But when he realized that rental and distribution companies were reluctant to book his releases into white theaters, his optimism turned to frustration. This “de facto economic boycott of the first black film producers,” according to Henry T. Sampson, “gave birth to a separate black film industry in the United States,” which “during the next forty years produced over 500 films featuring blacks which were shown in theaters catering to blacks with little distribution anywhere else.”18 Yet Foster would not share in that success. Although he went on to produce a few more shorts, he quit the business in 1917 to become circulation manager of the Chicago Defender, which he helped to make one of the most widely distributed black newspapers.

In 1928, hoping to resurrect his film career, Foster moved to Los Angeles, where he directed for the Pathé Studios a series of musical shorts featuring such legendary black performers as Clarence Muse, Stepin Fetchit, and Buck and Bubbles. He also began selling stock subscriptions to revive his Foster Photoplay Company and struggled bitterly “trying to get somewhere in this Business as a Producer,” because he realized that “if a colored producing co don’t make the Grade now it will be useless later on after all the Big Co.s get merged up—they will set about controlling the Equipment then the door wil be closed.”19 His assessment was ultimately correct, and his company released no new films.

Foster’s early shorts were amusing if unsophisticated efforts that followed the generic formulas of the day. But while they poked fun at “dishonest and vain black urban types,” his comedies also “reflected the vibrant culture African Americans were developing in cities” and featured a range of “New Negro” characters, such as the well-traveled Pullman porters who served as conduits of vital news and information about the cities that they visited on their routes and who were often treated as culture heroes within the black community.20 The Railroad Porter (1912), for instance, which was the first racial comedy and which “inaugurated the ‘chase’ idea later copied by [the] Lubin Company, Keystone Cops and others,” told the story of a young wife.21 Thinking her husband is out on his run, she invites to dinner a finely dressed man who turns out to be a waiter. After the husband returns home, he pulls out his gun; the waiter, according to the New York Age (September 25, 1913), “gets his revolver and returns the compliment … no one is hurt … and all ends happily.”22 And in The Barber (1912), a barber posing as a Spanish music teacher engages in a series of comedic chases as he tries to evade an angry husband, the local police, and even an old woman whose boat he overturns when he jumps in a lake to avoid capture. Yet, though well received by audiences and favorably reviewed in local Chicago papers, Foster’s shorts (none of which is extant) were rarely shown outside the Midwest; and his players, despite their strengths as stage actors, failed to attract national recognition as film stars, even in the black press.

Still, Foster’s efforts marked an important beginning and a significant break “with the ‘coon’ tradition established by Thomas Alva Edison’s Ten Pickaninnies (1904) and The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon (1905) as well as Seigmund Lubin’s Sambo and Rastus series (1909, 1910, and 1911)” that were so popular in the early years of motion pictures.23 Defying some of the early racial stereotypes in that “men are employed, marriages do take place, businesses are owned and operated by blacks, and violence does not conclude” every film, Foster’s progressive, realistic, and culturally specific comedies were consistent with the ideology of racial uplift.24 Moreover, Davarian L. Baldwin observed, by portraying black porters, barbers, and butlers as “hardworking heroes,” those comedies combined “sensational entertainment with moral instruction to make the behaviors of laziness, indecency, and immodesty the subject of laughter” and promoted “cinema [as] a respectable enterprise and entertainment.”25 Thus Foster remains a seminal figure in cinema history.

...