- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian

About this book

Originally released as a videographic experiment in film history, Jean-Luc Godard's Histoire(s) du cinéma has pioneered how we think about and narrate cinema history, and in how history is taught through cinema. In this stunningly illustrated volume, Michael Witt explores Godard's landmark work as both a specimen of an artist's vision and a philosophical statement on the history of film. Witt contextualizes Godard's theories and approaches to historiography and provides a guide to the wide-ranging cinematic, aesthetic, and cultural forces that shaped Godard's groundbreaking ideas on the history of cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian by Michael Witt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Histoire(s) du cinéma: A History

PREHISTORY OF THE PROJECT

Looking back on the early stages of his film history project from the perspective of 1979, Godard suggested that his desire to actively investigate cinema history had originated in a growing confusion he had experienced around 1967 or 1968 regarding how to proceed artistically. He realized that what he needed to sustain and renew his creative practice as a filmmaker was a deeper and more productive understanding of the relationship between his own work and the discoveries of his predecessors, and felt a thorough dissatisfaction in this regard with written histories of cinema:

Little by little I became interested in cinema history. But as a filmmaker, not because I’d read Bardèche, Brasillach, Mitry, or Sadoul (in other words: Griffith was born in such and such a year, he invented such and such a thing, and four years later Eisenstein did this or that), but by ultimately asking myself how the forms that I’d used had been created, and how such knowledge might help me.1

His approach to the making of history through the bringing together of disparate phenomena as the basis for the creation of poetico-historical images can be traced back as far as the late 1960s. In the course of a 1967 televised discussion of the relationship between people and images, for instance, he was already starting to think about cinema from a historical perspective and to formulate the central principle of his later historiographic method:

I’m discovering today that Griffith was the contemporary of mathematicians such as Russell or Cantor. At the same moment that Griffith was inventing the language of cinema, roughly the same year, Russell was publishing his principles of mathematical logic, or things like that. These are the sorts of things I like linking together.2

Moreover, even in his early work, he had in many ways been a conceptual montage artist. As early as 1965, Louis Aragon, we recall, had perspicaciously characterized him, as a “monteur” in the manner of Lautréamont: “What is certain is that there was no predecessor for [Delacroix’s] Nature morte aux homards, that meeting of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissection table in a landscape, just as there is no predecessor other than Lautréamont to Godard.”3 His theorization of the task of the historian, his approach to cinema history, and his reflection on history more broadly, all flowed directly from this longstanding experimentation with montage.

The earliest trace of Godard’s film history project dates from 1969, when he and Jean-Pierre Gorin sketched a brief history of cinema through a collage of images, quotations and handwritten text, as part of an abandoned book project entitled Vive le cinéma! or À bas le cinéma! (Long live cinema! / Down with cinema!).4 This was also the year of Vent d’est, which, as Alberto Farassino has suggested, can be read not only as an experimental political film, but also as an historical interrogation of the Western, of the costume drama genre, of Hollywood, and of the birth of photography.5 Godard’s drive to investigate cinema history was fueled in the early years by an acute awareness of the profundity of the changes to cinema brought about by the spread and effects of television, coupled with a concern for what he considered growing amnesia in relation to cinema’s past artistic achievements, and a loss of understanding regarding the methods and techniques that had made them possible. While shooting Tout va bien in 1972 with Gorin, for instance, the duo attempted to model a shot on the sequence depicting Vakoulintchuk’s death in Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), and discovered that the secrets behind the insights of the great poet-filmmakers of the silent era, in areas such as framing, montage and rhythm, appeared to have been forgotten. Their attempts to reproduce them resulted in a sense of ungainly imitation: “[W]e realized something very simple: that we didn’t know how to make an angle in the way that Eisenstein did; if we tried to film someone with their head bent slightly forward looking at a dead person, we had absolutely no idea how to do it. What we did was grotesque!”6 By 1973, Godard’s venture, known at that point under the working title Histoire(s) du cinéma: Fragments inconnus d’une histoire du cinématographe ([Hi]stories of cinema: Unknown fragments of a history of the cinematograph), already included a spread of themes – debated with Gorin over the preceding four years – that would recur throughout much of his ensuing work:

How Griffith searched for montage and discovered the close-up; how Eisenstein searched for montage and discovered angles; how von Sternberg lit Marlene in the same way that Speer lit Hitler’s appearances, and how this led to the first detective film; how Sartre made Astruc wield the camera like a pen so that it fell under the power of meaning and never recovered; true realism: Roberto Rossellini; how Brecht told the East Berlin workers to keep their distances; how Gorin left for elsewhere and didn’t come back; how Godard turned himself into a tape recorder; how the conservation of images by the board of directors of the Cinémathèque française operates; the fight between Kodak and 3M; the invention of Secam.7

During the mid- to late 1970s, Godard pursued his plan – or at least an explicitly autobiographical variation thereon, which focused in particular on his incomplete projects – under the working title Mes films, commissioned by the Société française de production (SFP). However, while Godard grappled with this film for three years, he was ultimately overwhelmed; he refunded the development money and conceded defeat: “I was branching off in every direction, and it was turning into an impossible film: two hundred thousand hours, and I didn’t even have enough of my life left to make it.”8 Throughout this decade, Godard made regular allusions to the embryonic Histoire(s) du cinéma in interviews and working documents, including the script of his major abandoned project of this period, Moi je, the closing five pages of which are presented as “a few as yet very incomplete fragments” of “a true history of cinema,” and include what would become over the ensuing decades a central strand of reflection on Eisensteinian and Vertovian montage theory.9

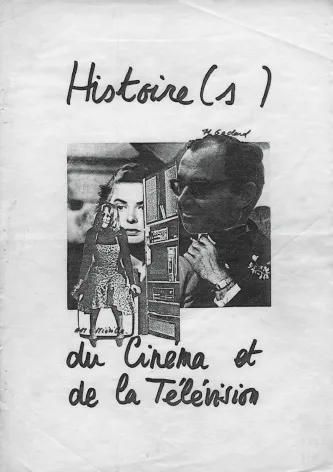

The most important early document relating to Histoire(s) du cinéma to have come to light is a twenty-page English-language collage he made in the mid-1970s, in which he outlined his plans with Anne-Marie Miéville for a series of “Studies in art, economics, technics [sic], people” under the title “Histoire(s) du cinéma et de la télévision”/“Studies in Motion Pictures and Television.” The document probably dates from between 1974 and 1976, since it employs a number of images also used in Ici et ailleurs and Six fois deux (Sur et sous la communication) (co-dir. Miéville, 1976). In any case, the final page suggests that it was produced while Godard and Miéville were still based in Grenoble, rather than in Rolle, Switzerland, to where they relocated their Sonimage company in 1977. The document gives a good deal of precise information not only about the organization and contents of the proposed series, but about the budget and technology they planned to use. It envisages ten one-hour videocassettes (masters to be produced in 2-inch NTSC), each one budgeted at $60,000–$100,000, with a proposed sale price of $250–$500 each. According to this document, the whole series was to be completed in two phases over two years: five cassettes were to be fabricated in the first year, and five in the second. The main organizing principle was that of a division between silent and sound cinema: (1) “Silent U.S.A.,” (2) “Silent Europe,” (3) “Silent Russia,” (4) “Silent Others,” (6) “Talking U.S.A.,” (7) “Talking Europe,” (8) “Talking Russia,” (9) “Talking Others.” Cassettes 5 and 10 are described not in thematic terms, but rather as an introduction and summing up. The outlines of the episodes given in this document point to significant continuity between this early prototype, Godard’s ongoing concerns as the project developed, and the final version of Histoire(s) du cinéma. Cassette 7 (“Talking Europe”), for instance, proposes an unorthodox approach to the star system (“the west side story of the star system”), which is illustrated by a comparison of Albert Speer and Hitler on the one hand, and Joseph von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich on the other. This juxtaposition recurs across Godard’s work from the early 1970s to the 1980s and beyond (see the 1973 document cited above): “Bring together a close-up of Dietrich, lit by the man who loved her, with another close-up, organized by the minister for equipment, to light the face of the man he loved at the time: Adolf Hitler.”10 Similarly, cassette 2 (“Silent Russia”) presents in synoptic form, through reference to the celebrated sequence depicting the apparent rising up of the stone lions in Battleship Potemkin, a line of thinking that culminates in 1A and 3B: Godard’s thesis regarding Eisenstein’s discovery not of montage, but rather of the effects that can be achieved through the combination of different angles in editing.

In December 1976, Henri Langlois and Godard announced a joint project for an audiovisual history of cinema, which they would cowrite and co-direct for release on film and videocassette.11 It was to be financed and produced by Jean-Pierre Rassam, whose position at Gaumont in the early 1970s had already been instrumental in allowing Godard and Miéville to experiment extensively with video technology. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Langlois had been lecturing widely, having first accepted an invitation from Serge Losique in April 1968 to commute to Montreal from Paris every three weeks for a period of three years, beginning in the autumn of that year. Born Srdjan Losic in the former Yugoslavia, Losique, who would go on to found and direct the Montreal World Film Festival, was at that point a professor in the French department at Sir George Williams University (one of two institutions that merged in 1974 to form Concordia University), where he taught French film.12 In 1967, Losique had founded the Conservatoire d’art cinématographique as a film archive and repertory cinema under the auspices of the university. It was here that Langlois embarked on his now legendary Montreal “anti-lectures,” during which he would project reels of films and deliver semi-improvised three-hour talks to students. These anti-lectures were followed in the early 1970s by similar engagements in Washington, D.C., Harvard, and Nanterre. The 1976 prototypical vision of Histoire(s) du cinéma conceived by Godard and Langlois was almost immediately abandoned, however, due to the latter’s untimely death in January 1977. In March, Godard traveled to Montreal to present a season of twenty-two of his films at the Conservatoire.13 During this visit, he pursued discussions with Losique, which were already underway, of the possibility of his picking up where Langlois had left off.14 In August, at the time of the inaugural edition of Losique’s festival, he returned again for further exploration of the idea of a series of unorthodox film history lectures, which he envisaged as investigative research for his true history of cinema and television:

Cover page of an outline of Histoire(s) du cinéma by Godard from the mid-1970s.

Collection Wilfried Reichart.

I’ll soon be fifty, which is generally the time that people write their memoirs and recount what they’ve done. But rather than writing those memoirs, and saying where I come from, and how it is that I’ve happened to have taken the journey that I have in this profession of mine, the cinema, rather than doing that, I’d like to tell my stories, a little like tales about cinema. And that’s what I’m intending to do. There will a dozen courses, which will lead to a dozen cassettes, and, perhaps later on they will produce some more elaborate works.15

So began Godard’s film history experiment in Montreal.

Despite his deep admiration for Langlois, Godard was not always in full agreement with his mentor. As he stressed to Losique, it would therefore be less a question of him taking over from Langlois than of continuing the work in another way.16 The original plan had been for Godard to begin delivering his talks in fall 1977. Although this slipped to spring 1978, he started commuting regularly from Rolle to Montreal in April, and delivered fourteen of a proposed twenty lectures on consecutive Fridays and Saturdays at various points throughout the year. The lectures took place on 14–15 April, 5–6 May, 9–10 June, 16–17 June, 6–7 October, 13–14 October, and 20–21 October; further visits were planned for December but did not take place. He envisaged the talks as the first concrete step on an open-ended journey into what he termed the “completely unknown territory” of cinema history, and ant...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Godard’s Theorem

- Chapter: 1. Histoire(s) du cinéma: A History

- Chapter: 2. The Prior and Parallel Work

- Chapter: 3. Models and Guides

- Chapter: 4. The Rise and Fall of the Cinematograph

- Chapter: 5. Cinema, Nationhood, and the New Wave

- Chapter: 6. Making Images in the Age of Spectacle

- Chapter: 7. The Metamorphoses

- Envoi

- Works by Godard

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index