eBook - ePub

Quick Hits for Teaching with Technology

Successful Strategies by Award-Winning Teachers

- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Quick Hits for Teaching with Technology

Successful Strategies by Award-Winning Teachers

About this book

"A wealth of good ideas" for using technology in education, from increasing student engagement to managing hybrid and distance learning (

Teachers College Record).

How should I use technology in my courses? What impact does technology have on student learning? Is distance learning effective? Should I give online tests and, if so, how can I be sure of the integrity of the students' work? These are some of the questions that instructors raise as technology becomes an integral part of the educational experience.

In Quick Hits for Teaching with Technology, award-winning instructors representing a wide range of academic disciplines describe their strategies for employing technology to achieve learning objectives. They include tips on using just-in-time teaching, wikis, clickers, YouTube, blogging, and GIS, to name just a few. An accompanying interactive website enhances the value of this innovative tool.

How should I use technology in my courses? What impact does technology have on student learning? Is distance learning effective? Should I give online tests and, if so, how can I be sure of the integrity of the students' work? These are some of the questions that instructors raise as technology becomes an integral part of the educational experience.

In Quick Hits for Teaching with Technology, award-winning instructors representing a wide range of academic disciplines describe their strategies for employing technology to achieve learning objectives. They include tips on using just-in-time teaching, wikis, clickers, YouTube, blogging, and GIS, to name just a few. An accompanying interactive website enhances the value of this innovative tool.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PROMOTING ENGAGEMENT

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFORMING LEARNING

GREGOR NOVAK

PROFESSOR EMERITUS, DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PURDUE UNIVERSITY INDIANAPOLIS

Learning technologies should be designed to increase,

and not to reduce, the amount of personal contact between students and faculty on intellectual issues.

(Study Group on the Conditions of Excellence in American Higher Education, 1984)

In the May 13, 2011 issue of Science, Louis Deslauriers and colleagues report the results of an interesting experiment conducted at University of British Columbia (Deslauriers, Schelew, & Wieman, 2011). In the words of the authors:

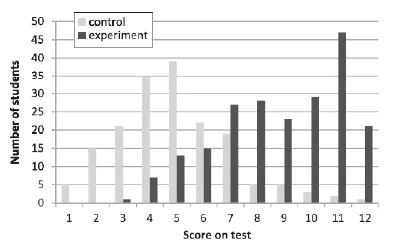

“We compared the amounts of learning achieved using two different instructional approaches under controlled conditions. We measured the learning of a specific set of topics and objectives when taught by 3 hours of traditional lecture given by an experienced highly rated instructor and 3 hours of instruction given by a trained but inexperienced instructor using instruction based on research in cognitive psychology and physics education. The comparison was made between two large sections (N = 267 and N = 271) of an introductory undergraduate physics course. We found increased student attendance, higher engagement, and more than twice the learning in the section taught using research-based instruction.”

“The instructional approach used in the experimental section included elements promoted by CWSEI and its partner initiative at the University of Colorado: pre-class reading assignments, pre-class reading quizzes, in-class clicker questions with student-student discussion (CQ), small-group active learning tasks (GT), and targeted in-class instructor feedback (IF). Before each of the three 50-min classes, students were assigned a three- or four-page reading, and they completed a short true false online quiz on the reading.”

Figure 1.1. Compared achieved learning.

The rather striking results of this experiment highlight two important trends that research into teaching and learning has spawned during the past three decades (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). The first is the realization that replacing passive environments, even if presided over by charismatic, knowledgeable and engaging presenters, with active student-centered pedagogies leads to superior learning outcomes.

The second trend, without which the first would be much less effective, is the growing use of technology, inside and outside of the classroom.

The key features of the Deslauriers experiment are: pre-class reading assignments, pre-class reading quizzes, in-class clicker questions with student-student discussion, small-group active learning tasks, and targeted in-class instructor feedback. All of these parts carefully aligned with one another and all of it informed by education research. The students were actively involved in carefully planned activities at all times. Technology, supporting the experience in and out-of-class, was brought in as needed by the pedagogy involved. An experiment similar to the one above, but more narrowly focused, was recently conducted at North Georgia College & State University (Formica, Easley, & Spraker, 2010).

Student centered activity-based lessons and the use of information technologies in teaching and learning are work in progress, but the evidence from the classroom indicates that we are on the right track.

The two critical theoretical underpinning of these efforts are constructivism and cognitivism. To learn means to construct meaning rather than memorize facts. Student-instructor, student-student and student-content interactions, facilitated by the use of technology, drive the effort. These interactions encourage students to assume some ownership of and control over their learning, provide realistic and relevant contexts and encourage the exploration of multiple perspectives and metacognition. Cognitive science research into how the human brain processes and stores information provides the theoretical basis for lesson designs. Learning tasks are constructed to engage the learner in the learning process, to scaffold the learning as needed to foster the development of understanding, and to provide timely and meaningful feedback.

Technical tools have been assisting learning since the cave paintings. Arguably, serious large-scale use of the technology in teaching and learning can be traced to the educational films developed for the large number of servicemen returning from WWII. Media-based presentations of educational materials are still with us with Power Point and streaming video and audio. The fifties saw the emergence of two major designs, programmed instruction and mastery approach. In programmed instruction the material to be learned is broken up into small units, incorporating frequent feedback and correction. Mastery approach is based on Bloom’s taxonomy of intellectual development.

These forms of instruction have evolved into CAI, computer-based and computer-assisted instruction, still with us today. During the 1980s and 1990s computer environments were developed where learners can build, explore, and immerse themselves in micro-worlds and simulations. Another major step was taken when the world-wide-web was made public in the mid-nineties, paving the way for computer-mediated-communication, CMC, which creates an always-open communication path for student-instructor, student-student and student-content interaction. CMC also provides tools for the maintenance of learning communities and for course and curriculum management. The internet has made possible the creation of distance learning, courses fully online, as well as hybrid designs, such as Just-in-Time Teaching, blending on-line work and in-class activities with live teachers. The next advance is likely to come when the mobile technologies of today are harnessed in the service of teaching and learning (Sharples, Milrad, Arnedillo Sánchez, & Vavoula, 2009). The audience for this is the next generation of students, growing up with these tools (Schachter, 2009). An astounding number of very young children are users of mobile technologies (Gutnick, Robb, Takeuchi, & Kotler, 2010). Seventy-five percent of 5 - 9 yr-olds use cell phones.

There is not much doubt that student-centered instruction, facilitated by available technology, is here to stay in one form or another. The question debated in the educational research community is: how does one optimize the many benefits of the new paradigm: easy access to course materials, improved student motivation and participation (Kulik & Kulik, 1991), differential instruction serving different learning styles, etc. Resource availability and cost issues aside, and there are many, the intellectual challenge is to find the proper balance between technology tools and live human interactions. The pedagogical strategies must follow from evidence-based science of learning or instruction. The past several decades have seen the emergence of discipline-based education research such as PER in physics and a deeper understanding of the learning process through cognitive science research (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000).

For learning to be effective, the learning activities must be designed to work in harmony with the human cognitive system. Cognitive science can help optimize the delivery of information to the learner by determining what is critical, what is salient and most directly valuable to the cognitive system (Dror, 2008). Cognitive science studies, combined with discipline-based pedagogical research, can help us choose technologies appropriate for the task. Technology can emphasize the relevant with correct use of color and animation for example. Technology can be the servant of the pedagogy or can become the tyrant. Misuse of technology in teaching and learning is not uncommon and hard to guard against (Tufte, 2003; Norvig, 2003). Technology is frequently employed to process larger numbers of students with fewer live instructors. But even in the absence of mercenary motives and with the best intentions, technology can be misapplied. It is tempting to take advantage of technology to let the student loose with the content in the name of ownership and control over the learning process. But research has shown that guided and structured exploration is more effective than free-for-all constructivism. “Minimally guided instruction is less effective and less efficient than instructional approaches that place a strong emphasis on guidance of the student learning process. The advantage of guidance begins to recede only when learners have sufficiently high prior knowledge to provide ‘internal’ guidance” (Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006).

How does one go about appropriately incorporating technology into ones teaching? A good start is getting familiar with educational research results, including cognitive science research, of the last three decades. The “How People Learn” book is a good start. The second step would be a good look at the pedagogical research literature in one’s discipline so that one would supplement the content knowledge required of an expert with the pedagogical content knowledge required of a teacher (Shulman, 1986). The third step would be a look at the literature, describing currently accepted best practices in the use of technology in teaching. This would include a general reference such as technology for teaching (Norton & Sprague, 2001) as well as technique and tool specific information: simulations (Adams, et. al., 2008), clickers (Caldwell, 2007) or JiTT (Simkins & Maier, 2009). Lastly, one would examine one’s personal teaching style and subject matter idiosyncrasies and choose the time and place where to include appropriate technology to best serve the intended learner. These are fun times with major developments taking place in the world of teaching and learning with something to fit every teaching and learning style.

Reference

Adams, W.K., Reid, S., LeMaster, R., McKagan, S.B., Perkins, K.K., Dubson, M., & Wieman, C.E. (2008). A study of educational simulations part I —Engagement and learning. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 19(3), 397-419.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C.: National Research Council, National Academy Press.

Caldwell, J. E. (2007). Clickers in the large classroom: Current research and best-practice tips, CBE Life Sci Educ, 6(1), 9-20.

Deslauriers, L., Schelew, E. & Wieman, C. (2011). Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class, Science, 332, 862-864.

Dror, I. E. (2008). Technology enhanced learning: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Pragmatics & Cognition, 16(2), 215–223.

Formica, S.P., Easley, J.L. & Spraker, M.C. (2010). Transforming common-sense beliefs into Newtonian thinking through Just-in-Time Teaching. Physical Review Special Topics - Physics Education Research, 6.

Gutnick, A.L., Robb, M., Takeuchi, L., & Kotler, J. (2010). Always connected: The new digital media habits of young children. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. Retrieved on July 14, 2011: http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/upload_kits/jgcc_alwaysconnected.pdf

Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R.E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, disc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Welcome to Quick Hits for Teaching With Technology

- Introduction Student Success is Our Mission

- 1 Promoting Engagement

- 2 Providing Access

- 3 Enhancing Evaluation

- 4 Becoming More Efficient

- Annotated Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Quick Hits for Teaching with Technology by Robin K. Morgan, Kimberly T. Olivares, Robin K. Morgan,Kimberly T. Olivares in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Tecnología educativa. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.