![]() Part 1. The Social Construction of Biotic Extinction

Part 1. The Social Construction of Biotic Extinction![]()

1. A SPECIES APART

IDEOLOGY, SCIENCE, AND THE END OF LIFE

Janet Chernela

In recent decades science has reached a critical juncture that calls our attention to its fundamental character and the contradictions within it. The crisis was brought about by the observation, by some scientists, that the Earth is facing a massive sixth extinction, one that may have been provoked by human activity. Reaction to this revelation has been complex; it points to some of the ways in which science is influenced by and inextricably integrated into the social fabric.

The degree to which science, as a pursuit of knowledge, is emancipated from the ideological underpinnings of society is an ongoing debate within the social and philosophical disciplines (Althusser 1971; Eagleton 1991; Giddens 1979). Theoretically, science and ideology represent two kinds of knowing, of which the first is open and the second closed. This profound difference has far-reaching implications, suggesting, among other things, that science reaches toward the unknown, whereas ideology continually reproduces itself. From the viewpoint of its proponents, science is an enterprise that not only is open to questions, but is built upon them.

In contrast, ideologies, the idea systems that we rely upon to make sense of the world, are (by definition) closed to challenge. They are intellectual strategies that allow us to organize chaotic phenomena into coherent conceptual schema. Although the reach of any ideology may be sweeping and capable of explaining such matters as, say, “human nature,” ideological schema are nevertheless based upon a few generating assumptions. Insofar as they are presented as universal or natural, ideologies discourage, rather than encourage, questioning.

The very act of employing the plural form “ideologies” undermines the totalizing power of any single scheme. The plural is important in this context, because an important source of an ideology’s power is its ability to appear as the only option. Anthropological inquiry is, however, based in comparison. It is the comparative viewpoint, present in anthropology since its founding in the nineteenth century, which enables its practitioners to regard all ideologies with the same degree of arbitrariness and to reflect on some of the ideologies that lie at the basis of Western thought and worldviews.

One of the ways in which science may serve society is by contributing to a belief in limitless possibility in which “Man” (First World, Western man, that is) is master of destiny, having attained this position through the domination and accumulation of knowledge. A fundamental tenet of this ideology is the definitive separation of humans from all other creatures, and the earned status of humans as inheritors of the Earth’s bounty. From this perspective, therefore, science may constitute part of the larger project of technological progress and Western hegemony that drives global economies of growth and celebrates human achievement.

Over the past two centuries, scientific accomplishment has provided a principal resource for optimism, confidence, and the celebration of Western achievement. That science has brought a sense of life, vitality, and possibility to the public has been apparent for some time. Its role in the forward motion of material accumulation and resource exploitation has been fundamental to its momentum. The science of extinctions, as findings and as sets of ideas, would thus appear to be an exception to the pattern.

A dramatic reduction in global biological diversity, brought about in part through activities deemed to be the fruit of advances in scientific knowledge, calls into question our assumptions about the scientific enterprise and the uses to which it is put. In this chapter, I briefly review the growing awareness of extinctions in order to consider what it tells us about the role of science in society.

Icons of Extinction: Objets Morts

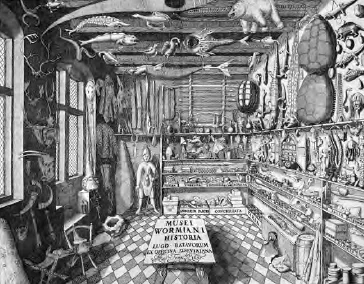

Visitors to the Wunderkammern and Cabinets du Roi (curiosity cabinets) of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries delighted in objets morts—the dried, stuffed, and bottled remains that evidenced a mysterious past (Olalquiaga 2006). Contained among the collections of naturalia were unidentified, mystifying objects from excavations. As citizens of a newly found progress, Europeans were fascinated with things passed, or morts. The greater the contrast with the present, the more entrancing the object. By looking back at a past populated by beings of grotesque difference, humans could place themselves at the apical meristem—the growing tip—of the future.

Figure 1.1. Ole Worm’s cabinet of curiosities. From Museum Wormianum (1655), in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries.

The discovery of the skeletal remains of the American mastodon in 1705 served as evidence of the existence and disappearance of an intriguing species. Exhibits of mastodons captivated Europe during the eighteenth century. In the American colonies the discoveries of mastodons coincided with a growing independence movement and a new national identity. In 1801 Thomas Jefferson, an avid collector of fossils and a student of extinctions, joined Charles Willson Peale in an expedition to exhume mastodon bones in upstate New York. The achievement was regarded as one of the important events in the history of American science and Peale mounted the gargantuan skeleton in his Philadelphia Museum, one of the first natural history museums in the United States. The specimen, displayed along with a murderer’s finger and an eighty-pound turnip, was considered the museum’s first successful attraction. The sensation was auctioned in 1849 and sold to bidder P. T. Barnum.

Peale wrote that the mastodon exhibit was a spectacular example of what he called democratic access to knowledge within a private institution (Barney 2006). Admission tickets to Peale’s Philadelphia Museum bore the words “The Birds and Beasts will teach thee!” (Yanni 1999:28). Years before the publication of On the Origin of Species, fossils such as these served to inspire conjecture about species change. Knowledge inhabited the very materials that served to convince onlookers of earlier species’ existence, and by inference, their demise. By the mid-nineteenth century a European subculture of gentleman fossil hunters had emerged. It was one of these, William Parker Foulke, who found the first nearly complete dinosaur skeleton while visiting Haddonfield, New Jersey, in 1858. Foulke’s findings were stunning. As he noted, the bones suggested an animal larger than an elephant that combined the structural features of lizards and birds. There was no context in which to comprehend a relationship between genera as apparently distant as these. Dinosaur fossils had been known in England since 1677, yet they went relatively unnoticed until 1824, when the accumulation of specimens and concomitant interest in them was sufficient to derive patterns and draw inferences. The evolutionary affinity between dinosaurs and birds was not understood until the end of the twentieth century, when it was hailed as a new finding, a contribution to the cumulative, forward movement of scientific knowledge.

Another icon of extinction, the flightless dodo (Raphus cucullatus), was discovered in Mauritius in 1581 but went extinct soon after with little public outcry. The demise of the dodo is directly attributable to the arrival of Europeans who overhunted the birds, destroyed their forested habitats, and introduced dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and macaques onto the island, where they ravaged nesting sites. The extinction of the dodo in the seventeenth century received little attention until the 1859 publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. In the surge of interest it prompted in species change and disappearances, new caches of dodo bones were unearthed and described to an avid public. In 1865 Lewis Carroll gave the dodo further prominence in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Since then the dodo has come to stand for extinction. Today a number of environmental organizations use the image of the dodo to promote the protection of endangered species.1

Charles Darwin, like others of his time, was intrigued by the fossils of extinct animals and plants. His observations of fossils and their comparisons to living species during his explorations on the H.M.S. Beagle contributed to the development of his theory that all life on earth evolved from a few common ancestors. Darwin’s evolutionary theory, which he published as On the Origin of Species in 1859, identified extinction as one of three principles underlying species change over time. Natural selection entails extinction; it brings about the survival of some species or varieties, but inevitably causes the extinction of others: “as new species in the course of time are formed through natural selection, others will become rarer and rarer, and finally extinct” (2010:48). He later continues, “Within the same large group, the later and more highly perfected sub-groups … will constantly tend to supplant and destroy the earlier and less improved sub-groups … [W]e already see how it [natural selection] entails extinction; and how largely extinction has acted in the world’s history, [as] geology plainly declares” (2010:58).

In order to consider “whether species have been created at one or more points on the earth’s surface,” Darwin observed the distributions of species on continents and islands and suggested that the relationships between island species and those of the nearest continent could best be explained by processes of migration and natural selection.

Using the model of the continent/island relationship, Darwin was able to draw generalities about the two principal axioms on which evolution is based: diversification and extinction.

Darwin wrote candidly about his personal challenge in assigning such prominence to the role of destruction in his theory.

The publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859 is a recognized watershed in biological science. Perhaps the greatest threat to Western ideology was not the common origin of all beings, as is assumed, but rather the possibility of a common ending: that all beings, humans among them, were subjected to the same forces and vulnerabilities. Insofar as it challenged orthodoxies, the appearance of Origin may be considered a “natural experiment” in the articulation and confrontation of different kinds of knowledge, open and closed. With its publication, social subjects were faced with their own conceptualized models of life on Earth and the place of humans within them.

The publication of On the Origin of Species represents a defining moment in science, at which it was confronted with the limits of its own autonomy. The processes and principles put forth in Origin could be extended to humans, but Darwin deliberately chose not to include that species in his descriptions and observations. At the time of his book’s publication, the place of humankind in the context of living creatures was a matter of heated debate. Darwin’s observations, if extended to human beings, would have been a direct challenge to the prevailing ideology. To avoid offense or sanction, Darwin, rather than entering the debate, left a hiatus in the text where a mention of humans might have been (although he was to correct this in subsequent publications). The deliberate omission underscored the importance of the absent message; the silence made by it was louder than any utterance might have been.

Preservation

The last half of the nineteenth century was a period of heightened interest in, concern with, and debate on the processes that drive species change. At the same time transportation innovations, industrial expansion, and empire building increased European contact with the periphery. The economic expansion was accompanied by a rush to collect knowledge about species never before known to Europeans, as well as concerns about species decline and efforts to protect wilderness areas. In 1866 the British Colony of New South Wales in Australia created Blue Mountains National Park, the first modern national park (Phillips 2004). This was followed by a series of parks, including Yellowstone National Park in the United States in 1872; Royal National Park in Australia in 1879; and Bow Valley, now Banff National Park, in Canada in 1885.

The following decade, between 1892 and 1902, witnessed the founding of the world’s first environmental organizations. The Sierra Club, founded in 1892 by the Scotsman John Muir, then living in California, was created to preserve wilderness areas as places of repose and beauty. In 1893 the British founded the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and in 1884 the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest and Natural Beauty (Epstein 2006:37). In 1902 the European nations signed the first international instrument to protect animals, the Convention to Protect Bird Species Useful in Agriculture (Epstein 2006:37).

Often cited as the earliest and longest-lived international animal protection association, the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire was founded ...