eBook - ePub

Ethics and the Problem of Evil

- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethics and the Problem of Evil

About this book

Provocative essays that seek "to turn the attention of analytic philosophy of religion on the problem of evil . . . towards advances in ethical theory" (

Reading Religion).

The contributors to this book—Marilyn McCord Adams, John Hare, Linda Zagzebski, Laura Garcia, Bruce Russell, Stephen Wykstra, and Stephen Maitzen—attended two University of Notre Dame conferences in which they addressed the thesis that there are yet untapped resources in ethical theory for affecting a more adequate solution to the problem of evil.

The problem of evil has been an extremely active area of study in the philosophy of religion for many years. Until now, most sources have focused on logical, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, leaving moral questions as open territory. With the resources of ethical theory firmly in hand, this volume provides lively insight into this ageless philosophical issue.

"These essays—and others—will be of primary interest to scholars working in analytic philosophy of religion from a self-consciously Christian standpoint, but its audience is not limited to such persons. The book offers illustrative examples of how scholars in philosophy of religion understand their aims and how they go about making their arguments . . . hopefully more work will follow this volume's lead."— Reading Religion

"Recommended."— Choice

The contributors to this book—Marilyn McCord Adams, John Hare, Linda Zagzebski, Laura Garcia, Bruce Russell, Stephen Wykstra, and Stephen Maitzen—attended two University of Notre Dame conferences in which they addressed the thesis that there are yet untapped resources in ethical theory for affecting a more adequate solution to the problem of evil.

The problem of evil has been an extremely active area of study in the philosophy of religion for many years. Until now, most sources have focused on logical, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, leaving moral questions as open territory. With the resources of ethical theory firmly in hand, this volume provides lively insight into this ageless philosophical issue.

"These essays—and others—will be of primary interest to scholars working in analytic philosophy of religion from a self-consciously Christian standpoint, but its audience is not limited to such persons. The book offers illustrative examples of how scholars in philosophy of religion understand their aims and how they go about making their arguments . . . hopefully more work will follow this volume's lead."— Reading Religion

"Recommended."— Choice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ethics and the Problem of Evil by Marilyn McCord Adams,John Hare,Linda Zagzebski,Laura Garcia,Bruce Russell,Stephen J. Wykstra,Stephen Maitzen, James P. Sterba in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Philosophical Essays. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1A Modest Proposal?

Caveat Emptor! Moral Theory and Problems of Evil

Catching Up on Moral Theory?

James Sterba has challenged philosophers of religion, not only those who work on the problem of evil, to take moral theory more seriously, for multiple reasons. Most obviously, good and evil, right and wrong, motivation in voluntary action, make up a large part of the subject matter of ethics. At least since positivism began to lose its grip, at least for the last sixty years, there has been a lot of fine-grained thinking on the subject (by Philippa Foot, Alan Gibbard, Christine Korsgaard, Alasdair McIntyre, Robert Nozick, John Rawls, and Tim Scanlon, among others). A variety of contrasting positions has been debated and worked out in detail.

By contrast, many treatments of the problem of evil have seemed ethically under nuanced. Back in the 1960s, but also later, there were appeals to ordinary moral sensibilities (e.g., by Nelson Pike). Others have commended as obviously acceptable principles ripped out of context: that an agent who did not produce the best (even where “best” is metaphysically impossible) would be morally defective (e.g., Rowe). Others have merely taken for granted principles or their applications, such as that God would be justified in making the best world that God could (Plantinga). Still others—some skeptical theists, including Justin McBrayer—confidently assume a thoroughgoing consequentialism. Recently, John Bishop and Ken Perszyk have reemphasized how responses to problems of evil are norm relative and noted how participants in the discussion often presuppose different moral norms.1 Overall, the state of debate in analytic philosophy of religion lends credence to the idea that wider and more nuanced acquaintance with moral theory would be a very good thing.

A Medieval Analogy

Because I am a medievalist, the idea of applying moral theory to philosophy of religion brings to mind Western scholastic appropriations of Aristotle and his Arab commentators, especially Avicenna and Averroes. Aristotle was dubbed “the Philosopher,” Averroes “the Commentator.” Together with others, they formed a philosophical canon to which would-be philosophers and philosophical theologians put themselves to school. Medieval Latin scholastics had a lot to gain from this. Aristotle had fenced off, and Aristotle and his commentators had ploughed and cultivated many fields and subfields. They had set important questions and pursued them with analytical skill and technical precision. They had developed conceptuality, categories and distinctions for managing issues in metaphysics, epistemology, psychology, and morals. They had offered systematic theories in each. What medievals stood to gain by engaging these was philosophical training and a leg up on wide-ranging issues. They simply didn’t have to reinvent the wheel. They had a place to start, research programs to participate in and continue, questions to pursue, theories to refine.

Nevertheless, putting themselves to school did not mean uncritical appropriation. They read, marked, learned, and inwardly digested the texts of the philosophers, the better to be in a position to question and dispute them. Small-scale refinements, applying them to shifting and new questions—that is what is always involved in carrying on a field. But absorbing as it was to understand Aristotle’s ideas and extend his research programs, Christian philosophers soon recognized that the philosophical systems of Aristotle and the Arab commentators needed more than minor tweaking. Christian theology widened the data base of phenomena to be preserved and accounted for: creation ex nihilo, the Trinity, the Incarnation, Eucharistic presence. This meant that Aristotle’s metaphysical categories and taxonomy of causation and understandings of corporeal placement required substantial conceptual revision and innovation. Christian theology implied that there were points on which Aristotle was clearly wrong, for example about whether the unmoved mover was an efficient cause of the existence of the world, about whether motion and time were without beginning or end, about whether the world here below is necessary, about whether future contingents could be knowable determinately and with certainty. The condemnations of 1270 and 1277 issue emphatic caveats. In effect, they warned, “Impressive as they are, you have to use what Aristotle, Avicenna, and Averroes say with caution. By all means, get inside and understand their theories. But then question and dispute them. Don’t lose sight of important points that you need to accommodate.”

Overall, it was a very fruitful engagement, arguably one which has given both Aristotle and Christian worldviews a longer academic run. Twentieth century theological critics to the contrary, notwithstanding, theology had a lot to learn from Aristotelian philosophy. What is less often noticed is that Aristotelian philosophy had things to learn from theology: the possibility of something incorruptible being the form of some matter, the possibility of an individual substance nature being alien-supposited and/or multiply supposited, the possibilities of multiple locations for bodies, efficient causality as an explanation of being and not just of locomotion and/or material transformation.

Evil and Problems with Morality

So also and all the more so if philosophers of religion get more nearly up to speed with what contemporary moral theories have to offer.

To this, my honest response has to be: “Caveat emptor.” Certainly, it will not do for us simply to pick one of the ethical theories on offer, let it tell us what counts as evil and what it would take for an agent to be perfectly good, and grind out the results. Claudia Card points to one reason: many prominent ethical theorists skirt the topic of evil. W. D. Ross does not even mention it in The Right and the Good. Nor does the term “evil” appear in the index to Henry Sidgwick’s The Methods of Ethics. John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice contains only one mention of “the evil man.” Even more telling, Rawls’s concern with the distribution of primary goods that any person may be presumed to desire is not matched with any balancing consideration of basic harms to be avoided in the ideal society.2 How can such theories help us wrestle with problems of evil, when they seem to sweep problems with evil under the rug?

Indeed, in my past work on problems of evil, I have argued for de-emphasizing the role of moral theory. Shifting attention from abstract to concrete problems of evil—from the issue of whether the existence of God is compatible with some evil or other to the question of whether an omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good God could have produced human beings in a world with evils in the amounts and of the kinds and with the distributions found in the actual world—I have often spoken of the poverty of morality, and rubbed readers’ noses in its difficulty in conceiving, much less managing the difficulties raised by the worst evils. I have put forward the idea that other systems of evaluation—namely, the purity and defilement calculus and the honor code—outstrip contemporary moral theory when it comes to capturing what is at stake with the worst evils and to identifying the obstacles to harmonious Divine-human relationships.3

Mostly, my suggestions have been met with incomprehension and mockery. Do I seriously think that we should replace modern morality (note the hint that the term is univocal and its referent obvious) with the holiness code, evaluations of morally right and morally wrong with the verdicts “tainted” and “undefiled”? Do I really believe that the challenge and riposte of the honor code would be a good substitute for talk of virtue and vice? Do I really want to go back to evaluating social behavior like the Dinkas, or is the feudal world of Don Quixote (I am a medievalist after all) my all-things-considered choice?4

My response to such rhetorical questions is that I was not simply being silly. I meant to make three serious points. First, I wanted to warn colleagues against anachronistic eisegesis. Many biblical passages, like many traditional theological teachings, are framed by the holiness and/or honor codes. It is unfaithful to the (in this case, authoritative) texts and so misleading to read modern moral theories into them.

Second, I wanted to call attention to the fact that—however much they may have gone underground—the holiness and honor codes have not disappeared from our evaluative practices. Sexual sins still defile and certain kinds of graft blot the politician’s copybook. Philosophical colloquia provide ready evidence that competition for honor, the need to show how much there is to us philosophically is alive and well.

Third, and most important for present purposes, I wanted to show how these frameworks do a better job of getting at what’s so bad about the worst evils and of suggesting what might be done to remedy them. My thought was and is that putting ourselves to school to these neglected value frameworks might refocus our attention and sensitize us to factors that moral categories blindside. My thought was and is that getting inside these evaluative frameworks enough to understand how they work might put us in touch with neglected resources for both formulating and resolving problems of evil.

A More Modest Proposal

If there is anything to my medieval analogy, however, Sterba and other conference-organizers were not aiming for Christian philosophers to “read, mark, learn” and “swallow whole” what contemporary ethical theory has to offer. Rather, they are urging that we “read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest” them, the better to question and dispute them, the better to assess how they need to be “transmogrified” in the face of Christian theological commitments.

For the sake of argument, let me back off a bit from my most negative verdicts about moral theory. Let me take a page from Claudia Card, who does not want to abandon moral theory but to supplement and rejig theories of moral wrongness that fail to grapple with the worst evils. Instead of writing off ethical theories in advance, let me try once again to rivet attention on five factors that—in my judgment—any theologically adequate ethical theory will have to address seriously.

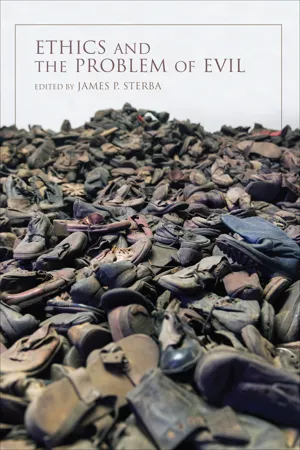

Facing the Worst

Honest wrestling with problems of evil requires us to face up to the worst that we can suffer, be, or do. Several rubrics have been proposed for picking out the worst. For my own part, I have proposed the category of horrendous evils (for short, horrors), which I have defined as “evils participation in which constitutes prima facie reason to believe that the participant’s life cannot be a great good to him/her on the whole” or “prima facie life-ruinous evils.” As dramatic examples, I have instanced the rape of a woman and axing off of her arms, psycho-physical torture whose ultimate goal is the disintegration of personality, cannibalizing one’s own offspring, child abuse of the sort described by Ivan Karamazov, participation in the Nazi death camps, the explosion of nuclear bombs over populated areas, avoidable death by starvation of populations driven off their land by hostile forces or natural disasters, being the accidental and/or unwitting agent in the disfigurement or death of one loves best. Domestic examples include corporate cultures of dishonesty that coopt workers into betraying their deepest values, schoolyard bullying, parental incest, clinical depression, schizophrenia, degenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s that imprison and/or unravel the person we once knew.

Claudia Card advances her atrocity paradigm, which she defines as “foreseen intolerable harms produced by culpable wrong-doing.”5 Alternatively, she speaks of harms that deprive or seriously risk “depriving others of the basics that are necessary to make a life possible or tolerable or decent,” where a “ ‘tolerable’ life is at least minimally worth living for its own sake and from the standpoint of the being whose life it is, not just as a means to the ends of others.”6 Her list of examples overlaps mine: “genocide, slavery, torture, rape as a weapon of war, saturation bombing of cities, biological and chemical warfare, unleashing lethal viruses and gases, domestic terrorism of prolonged battering, stalking, and child abuse.”7

Still others propose the rubric “unjustifiable.” Ivan Karamazov declares that his ghastly cases of child abuse cannot be swallowed up in the higher harmony. John Roth identifies the Nazi holocaust in particular, the “slaughter-bench of history” of which it is characteristic in general, as “waste” beyond justification.8 Likewise, D. Z. Phillips finds obscene any suggestion that the Nazi holocaust could be justified by “consequentialist” reasoning—as a means, consequence, or side effect to obtaining some great good or avoiding an equally bad or worse evil.9 In the same spirit, Stewart Sutherland charges that anyone who thinks the worst evils can be justified, does not take them with full moral seriousness.10

Perhaps all of these attempted rubrics need refinement. Even so, they combine with the examples to point us in the right direction.11 My contention has been and is that—where the worst evils are concerned—we cannot appreciate how bad they are or what’s so bad about them without engaging them face to face. By “face to face,” I mean either experiencing them in one’s own person (first-person experience) or through firsthand empathetic engagement. Moreover, once is not enough. Repeated or at least periodic confrontations are necessary to keep alive one’s sense of how ghastly they are.

Repeated face-to-face engagement is important, not only for apt conceptualization, but for accurate moral reasoning. The worst evils mess with our theories and demand that our theories become messier, because the worst evils cannot be subsumed under attractive generalizations that work well enough for the small, medium, and large evils of ordinary time. Job’s ruin explodes the act consequence principle (“good for good; evil for evil”). Terrorists’ torturing and beheading of journalists cannot be set right by lex talionis, by the state’s torturing and beheading terrorists. Ivan Karamazov insists that—unlike broken arms, skinned knees, and the common cold—bouncing babies on bayonets before their mothers’ eyes cannot be justified as constitutive means to the higher harmony. D. Z. Phillips is appalled at the suggestion that Sophie should consider her hands washed by the fact that she did what she had to do in the circumstances, that it was better to save one of her children than to let both be killed. Maternal betrayal of one child is not a morally acceptable means to saving the other.12

Horrors are difficult to domesticate theoretically. They require separate consideration. Not only that. Their prevention and (if possible) remedy deserves priority in deliberation and action.13 Not keeping the sense of ghastliness fresh makes it much easier to do the opposite. Consider the child sex abuse scandal in the Roman Catholic Church. Priests senior enough to become bishops and high-level archdiocesan officials did not lack an abstract conceptual grasp of the distinction be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Modest Proposal? Caveat Emptor! Moral Theory and Problems of Evil

- 2 Kant, Job, and the Problem of Evil

- 3 Good Persons, Good Aims, and the Problem of Evil

- 4 Does God Cooperate with Evil?

- 5 The Problem of Evil: Excessive Unnecessary Suffering

- 6 Beyond the Impasse: Contemporary Moral Theory and the Crisis of Skeptical Theism

- 7 Perfection, Evil, and Morality

- Conclusion

- Contributors

- Index