eBook - ePub

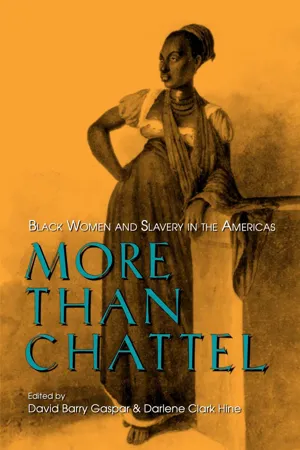

More Than Chattel

Black Women and Slavery in the Americas

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

More Than Chattel

Black Women and Slavery in the Americas

About this book

Essays exploring Black women's experiences with slavery in the Americas.

Gender was a decisive force in shaping slave society. Slave men's experiences differed from those of slave women, who were exploited both in reproductive as well as productive capacities. The women did not figure prominently in revolts, because they engaged in less confrontational resistance, emphasizing creative struggle to survive dehumanization and abuse.

The contributors are Hilary Beckles, Barbara Bush, Cheryl Ann Cody, David Barry Gaspar, David P. Geggus, Virginia Meacham Gould, Mary Karasch, Wilma King, Bernard Moitt, Celia E. Naylor-Ojurongbe, Robert A. Olwell, Claire Robertson, Robert W. Slenes, Susan M. Socolow, Richard H. Steckel, and Brenda E. Stevenson.

"A much-needed volume on a neglected topic of great interest to scholars of women, slavery, and African American history. Its broad comparative framework makes it all the more important, for it offers the basis for evaluating similarities and contrasts in the role of gender in different slave societies. . . . [This] will be required reading for students all of the American South, women's history, and African American studies." —Drew Gilpin Faust, Annenberg Professor of History, University of Pennsylvania

Gender was a decisive force in shaping slave society. Slave men's experiences differed from those of slave women, who were exploited both in reproductive as well as productive capacities. The women did not figure prominently in revolts, because they engaged in less confrontational resistance, emphasizing creative struggle to survive dehumanization and abuse.

The contributors are Hilary Beckles, Barbara Bush, Cheryl Ann Cody, David Barry Gaspar, David P. Geggus, Virginia Meacham Gould, Mary Karasch, Wilma King, Bernard Moitt, Celia E. Naylor-Ojurongbe, Robert A. Olwell, Claire Robertson, Robert W. Slenes, Susan M. Socolow, Richard H. Steckel, and Brenda E. Stevenson.

"A much-needed volume on a neglected topic of great interest to scholars of women, slavery, and African American history. Its broad comparative framework makes it all the more important, for it offers the basis for evaluating similarities and contrasts in the role of gender in different slave societies. . . . [This] will be required reading for students all of the American South, women's history, and African American studies." —Drew Gilpin Faust, Annenberg Professor of History, University of Pennsylvania

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access More Than Chattel by David Barry Gaspar, Darlene Clark Hine, David Barry Gaspar,Darlene Clark Hine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

AND

LABOR

2

WOMEN, WORK, AND HEALTH UNDER PLANTATION SLAVERY IN THE UNITED STATES

The large number of programs in black studies and in women’s studies created within the past two decades establish these areas as growth industries of academics. Accompanying this expansion has been a burgeoning literature on the involvement of these groups in the economy, society, and politics of the past. The role of women in economic history has attracted much attention and scholars have examined labor force participation rates of women by age and marital status, the degree of occupational segregation, and the nature of work in the home.1 Within the field of black history, participants have hotly contested issues in slavery, such as the profitability and relative efficiency of slave labor, the nature of the interregional and African slave trades, and demographic features of the slave system.2

Despite the popularity of research on women and blacks in general and interest in slavery and economic issues in particular, the overlap of these research areas is surprisingly small. Study of slave women has claimed little attention.3 Although the rationale for this neglect is elusive, an explanation might note that much of the agenda of current research on slavery was forged before the modern rise of women’s studies. The present generation of scholars is still grappling with issues, such as diet, disease, and the family, that were defined in the antebellum debate over abolition. Progress has been marked more by the assimilation of new data sources and techniques of analysis than by the formulation of new questions. On the other hand, many subjects in the spotlight of women’s studies, including labor force participation rates, pay scales, and political activity, hold little interest in the context of slavery. Yet women under slavery is a topic worthy of study in its own right, for learning, among other things, about performance under adversity and conditions that shaped life after emancipation.

Whatever the explanation for the lack of research about slave women, this chapter takes a step toward redressing the balance, using the concept of the life cycle to examine the course of work and health from childhood to old age in the United States. Particular attention is given to the health of pregnant women and to conditions on cotton plantations. The main sources of information include slave manifests, plantation records, slave narratives, probate records, and the census.

Diverse sources of evidence indicate that work was a central aspect of slave life. Virtually all studies that address the subject show that the initiation process began in childhood or early adolescence and, with the exception of infirmity and periods of illness or injury, slaves worked throughout their life span. The slave narratives indicate that few slaves escaped work in childhood: 48 percent of those who discussed the subject began working before age seven, 84 percent before age eleven, and only 7 percent reported that no work occurred before age fourteen.4 Child labor had a niche within the wide-ranging tasks required on a large farm. Young slaves picked cotton, carried drinking water to the fields, picked up trash, helped in the kitchen, fed chickens and livestock, minded young children, pulled weeds, and gathered wood chips for fuel. Although it is difficult to establish the intensity, duration, and physical demands of these jobs, it seems clear that the tasks were part of a real work experience that prepared the way for regular adult labor.

According to the narratives, male and female children had substantially different work experiences. Girls began work at younger ages and were involved more with housework than with fieldwork. One-half of the males and 21 percent of the females who worked as children participated regularly in fieldwork. Nearly 53 percent of the girls, but only 44 percent of the boys, who ever worked as children were working by age seven, but by age ten the numbers working were approximately equal. Females also began their adult jobs at younger ages; 71 percent of the girls but only 63 percent of the boys who mentioned the topic were performing their adult jobs before age fourteen. Girls not only began work earlier but were more productive than boys at certain tasks, such as picking cotton.5 This evidence is consistent with estimates of net earnings (value of labor minus maintenance costs) that show females were more productive than males before age seventeen.6 Explanations of this pattern note that girls matured earlier than boys and that boys may have been held out of work until they were productive in the fields. These patterns of work during childhood and adolescence suggest that the transition to adult labor required greater reorientation of females than males. The typical girl began her working life entirely or partially in the house but ended up in the fields, while the typical male spent his working life as a field hand. Adaptation to labor in the fields after working in the surroundings of the big house was an additional challenge posed for females by adolescence.

Although the distribution of skills and occupational mobility are contentious issues in slavery research, all accounts agree that a large majority of slaves spent their prime working years as field hands. On one side of the debate in the recent literature on this issue, Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman argued from probate records that only three-quarters of adult males were ordinary laborers and that the other slaves were skilled craftsmen, such as blacksmiths and carpenters; semiskilled workers, such as gardeners and coachmen; or managers.7 Semiskilled, and especially skilled, jobs were less available to women, 80 percent of whom labored in the fields. Most of the women not employed in fieldwork were servants, seamstresses, or nurses. Using plantation records and probate records, Fogel and Engerman also reported that skilled slaves tended to be older than field hands; 75 percent of all artisans were aged thirty or above, but only 46 percent of the males aged fifteen and above were thirty years or older.8 Fogel and Engerman used the information on the skill distribution by age and evidence on incentives to suggest that diligent slaves could have looked forward to upward mobility; masters reassigned slaves from fieldwork to one of the skilled or semiskilled crafts or household staff positions as a reward for diligent performance.

Herbert Gutman and Richard Sutch disputed the Fogel-Engerman account of upward mobility by challenging the representativeness of their sources, by offering alternative explanations, and by examining other sources of evidence.9 They pointed out that the probate records in question were atypical because the region of the sample (southern Louisiana) produced sugar, the holdings were large, and the age distribution was skewed toward males over fourteen years of age. It was also possible, they noted, that slaves too old or incapable of heavy work were transferred into less physically demanding jobs. Gutman emphasized that fewer than 3 percent of the troops from Kentucky who served in the Union Army reported their occupation as other than farmer or laborer.10 In pursuit of issues raised in the debate, Michael Johnson examined the distribution of skills reported on the mortality schedule of the 1860 census for certain counties in Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina. After adjustments for the age distribution of deaths, these data suggest that 77 to 91 percent of the males and 63 to 77 percent of the females were field hands. The percentages for women are below those reported by Fogel and Engerman, while the percentages for men were only moderately higher, which casts doubt on the Gutman-Sutch objections that the Fogel-Engerman sample is atypical. Of course, defenders of Fogel and Engerman would point out that the critics’ sources also have limitations. The Union Army records may undercount skilled slaves and servants because they were loyal to the system and had lower rates of enlistment, while skilled and semiskilled slaves may have had mortality rates below those of field hands. Longitudinal data (records that track characteristics of the same individuals over time) are needed to resolve questions about mobility. Patient sifting through a succession of plantation inventory lists that included names and occupations would provide valuable insights into the incentive structure. The evidence examined to date suggests that a modest minority of all slaves could look forward to regular adult labor in a skilled or semiskilled position, but whether women had relatively more of these positions than men remains an open question.

Whatever the distribution of skills and rewards, several sources confirm that slaves often worked hard at physically demanding tasks. The modern conveniences of home and workplace make it difficult for our generation to comprehend the rigors of slave labor. Yet the tools and methods typical of the era—hoes powered by human muscle and plows drawn by oxen, mules, or horses but guided by people—establish that fieldwork was demanding. The strains of physical exertion were relatively greater in farming, where workers were driven in gangs by overseers or drivers who could apply force. This style of work performance was frequently used in plowing, planting, or hoeing operations on large farms (roughly ten or more workers) that raised cotton or sugar. Work was probably less strenuous, but nonetheless demanding, on small farms, where slaves often worked with and were paced by the owner; on tobacco farms, where demands were more evenly spread throughout the year; and on rice farms, where the task system, which allowed workers some freedom to pace individual effort, was often used. The frequency and the detail of reports about slave labor from narratives and observers confirm the general high level of toil.11 Consistent with rigorous work, Fogel and Engerman estimated that slaves produced approximately 35 percent more output per year than free farmers.12 While there is disagreement over the size and meaning of their estimate, a good case could be made that the intensity of gang labor was an important source of the greater output.13

Although firm evidence is lacking about the ages at which older slaves were transferred from the most demanding fieldwork to less rigorous tasks, the process was probably under way as early as in the mid- to late thirties. Men and women once suitable for the plow gangs were moved to hoe gangs and, after further decline, to the lighter work of trash gangs. Movement out of regular fieldwork to positions of unpaced labor, such as weaver, seamstress, gardener, and stock minder, probably accelerated after slaves reached their late forties or early fifties. The age profile of net earnings mirrors the changing capacity for work. Annual net earnings reached a peak while slaves were in their early to mid-thirties.14 The maximum occurred approximately three to five years earlier among women than among men. As late as age fifty, however, net earnings were as large as 50 percent (women) to 70 percent (men) of the maximum. The gradual nature of the decline suggests that strength and endurance, while valuable, were not all that was required of a slave to make an important contribution to plantation operations. Farms made good use of a labor force that was diverse in capacity for work by allocating slaves to appropriate tasks. Remarkably, the net earnings of slaves as old as age seventy were, on average, greater than zero.15 Because fewer than 1.5 percent of all slaves above age nine were aged seventy or more, planters profitably employed nearly all slaves who were beyond the age of late childhood.

The labor demands of slavery inevitably affected other aspects of slave life, such as health, family interaction, recreation, and opportunities for personal reflection. Slaves tired from work in the fields must have had little enthusiasm for games and amusements and little time to spend with their children. There were slack periods, however, that occurred before and after the harvest, when celebrations and marriages often took place.16 Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of a slave’s adult life was spent engaged in or recovering from toil.

Hard work had adverse consequences for slave health. This topic is probed extensively here because health is fundamental to well-being and because recently developed evidence and techniques have added new dimensions of understanding, particularly in regard to pregnant women and their newborn children. Fogel and Engerman, using the disappearance method to estimate food consumption for adults as the difference between food production and nonslave utilization on large southern farms, argued that the diet was substantial calori-cally and exceeded recommended levels of the chief nutrients. Critics examined every step of this procedure and raised questions about methods of food preservation and cooking, the adequacy of the diet for blacks, and whether the diet was sufficient for the work effort required of slave...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Africa and the Americas

- Life and Labor

- Slavery, Resistance, and Freedom

- Selected Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index