![]()

1

Immortality in the Light of Synechism

The word

synechism is the English form of the Greek

from

continuous. For two centuries we have been affixing

-ist and

-ism to words, in order to note sects which exalt the importance of those elements which the stem-words signify. Thus,

materialism is the doctrine that matter is everything,

idealism the doctrine that ideas are everything,

dualism the philosophy which splits everything in two. In like manner, I have proposed to make

synechism mean the tendency to regard everything as continuous.

*For many years I have been endeavoring to develop this idea, and have, of late, given some of my results in the Monist.2 I carry the doctrine so far as to maintain that continuity governs the whole domain of experience in every element of it. Accordingly, every proposition, except so far as it relates to an unattainable limit of experience (which I call the Absolute), is to be taken with an indefinite qualification; for a proposition which has no relation whatever to experience is devoid of all meaning.3

I propose here, without going into the extremely difficult question of the evidences of this doctrine, to give a specimen of the manner in which it can be applied to religious questions. I cannot here treat in full of the method of its application. It readily yields corollaries which appear at first highly enigmatic; but their meaning is cleared up by a more thoroughgoing application of the principle. This principle is, of course, itself to be understood in a synechistic sense; and, so understood, it in no wise contradicts itself. Consequently, it must lead to definite results, if the deductions are accurately performed.

Thoroughgoing synechism will not permit us to say that the sum of the angles of a triangle exactly equals two right angles, but only that it equals that quantity plus or minus some quantity which is excessively small for all the triangles we can measure. We must not accept the proposition that space has three dimensions as strictly accurate; but can only say that any movements of bodies out of the three dimensions are at most exceedingly minute. We must not say that phenomena are perfectly regular, but only that the degree of their regularity is very high indeed.

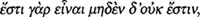

There is a famous saying of Parmenides,

, “being is, and not-being is nothing.”

4 This sounds plausible; yet synechism flatly denies it, declaring that being is a matter of more or less, so as to merge insensibly into nothing. How this can be appears when we consider that to say that a thing

is is to say that in the upshot of intellectual progress it will attain a permanent status in the realm of ideas. Now, as no experiential question can be answered with absolute certainty, so we never can have reason to think that any given idea will either become unshakably established or be forever exploded. But to say that neither of these two events will come to pass definitively is to say that the object has an imperfect and qualified existence. Surely, no reader will suppose that this principle is intended to apply only to some phenomena and not to others,—only, for instance, to the little province of matter and not to the rest of the great empire of ideas. Nor must it be understood only of phenomena to the exclusion of their underlying substrates. Synechism certainly has no concern with any incognizable; but it will not admit a sharp sundering of phenomena from substrates. That which underlies a phenomenon and determines it, thereby is, itself, in a measure, a phenomenon.

Synechism, even in its less stalwart forms, can never abide dualism, properly so called. It does not wish to exterminate the conception of twoness, nor can any of these philosophic cranks who preach crusades against this or that fundamental conception find the slightest comfort in this doctrine. But dualism in its broadest legitimate meaning as the philosophy which performs its analyses with an axe, leaving, as the ultimate elements, unrelated chunks of being, this is most hostile to synechism. In particular, the synechist will not admit that physical and psychical phenomena are entirely distinct,—whether as belonging to different categories of substance, or as entirely separate sides of one shield,—but will insist that all phenomena are of one character, though some are more mental and spontaneous, others more material and regular. Still, all alike present that mixture of freedom and constraint, which allows them to be, nay, makes them to be teleological, or purposive.

Nor must any synechist say, “I am altogether myself, and not at all you.” If you embrace synechism, you must abjure this metaphysics of wickedness. In the first place, your neighbors are, in a measure, yourself, and in far greater measure than, without deep studies in psychology, you would believe. Really, the selfhood you like to attribute to yourself is, for the most part, the vulgarest delusion of vanity. In the second place, all men who resemble you and are in analogous circumstances are, in a measure, yourself, though not quite in the same way in which your neighbors are you.

There is still another direction in which the barbaric conception of personal identity must be broadened. A Brahmanical hymn begins as follows: “I am that pure and infinite Self, who am bliss, eternal, manifest, all-pervading, and who am the substrate of all that owns name and form.”5 This expresses more than humiliation,—the utter swallowing up of the poor individual self in the spirit of prayer. All communication from mind to mind is through continuity of being. A man is capable of having assigned to him a rôle in the drama of creation; and so far as he loses himself in that rôle,—no matter how humble it may be,—so far he identifies himself with its Author.

Synechism denies that there are any immeasurable differences between phenomena; and by the same token, there can be no immeasurable difference between waking and sleeping. When you sleep, you are not so largely asleep as you fancy that you be.

Synechism refuses to believe that when death comes, even the carnal consciousness ceases quickly. How it is to be, it is hard to say, in the all but entire lack of observational data. Here, as elsewhere, the synechistic oracle is enigmatic. Possibly, the suggestion of that powerful fiction Dreams of the Dead, recently published,6 may be the truth.

But, further, synechism recognizes that the carnal consciousness is but a small part of the man. There is, in the second place, the social consciousness, by which a man’s spirit is embodied in others, and which continues to live and breathe and have its being very much longer than superficial observers think. Our readers need not be told how superbly this is set forth in Freytag’s Lost Manuscript.7

Nor is this, by any means, all. A man is capable of a spiritual consciousness, which constitutes him one of the eternal verities, which is embodied in the universe as a whole. This as an archetypal idea can never fail; and in the world to come is destined to a special spiritual embodiment.

A friend of mine, in consequence of a fever, totally lost his sense of hearing. He had been very fond of music before his calamity; and, strange to say, even afterwards would love to stand by the piano when a good performer played. “So then,” I said to him, “after all you can hear a little.” “Absolutely not at all,” he replied; “but I can feel the music all over my body.” “Why,” I exclaimed, “how is it possible for a new sense to be developed in a few months!” “It is not a new sense,” he answered. “Now that my hearing is gone I can recognize that I always possessed this mode of consciousness, which I formerly, with other people, mistook for hearing.” In the same manner, when the carnal consciousness passes away in death, we shall at once perceive that we have had all along a lively spiritual consciousness which we have been confusing with something different.

I have said enough, I think, to show that, though synechism is not religion, but, on the contrary, is a purely scientific philosophy, yet should it become generally accepted, as I confidently anticipate, it may play a part in the one-ment of religion and science.

![]()

2

What Is a Sign?

§1. This is a most necessary question, since all reasoning is an interpretation of signs of some kind. But it is also a very difficult question, calling for deep reflection.1

It is necessary to recognize three different states of mind. First, imagine a person in a dreamy state. Let us suppose he is thinking of nothing but a red color. Not thinking about it, either, that is, not asking nor answering any questions about it, not even saying to himself that it pleases him, but just contemplating it, as his fancy brings it up. Perhaps, when he gets tired of the red, he will change it to some other color,—say a turquoise blue,—or a rose-color;—but if he does so, it will be in the play of fancy without any reason and without any compulsion. This is about as near as may be to a state of mind in which something is present, without compulsion and without reason; it is called Feeling. Except in a half-waking hour, nobody really is in a state of feeling, pure and simple. But whenever we are awake, something is present to the mind, and what is present, without reference to any compulsion or reason, is feeling.

Second, imagine our dreamer suddenly to hear a loud and prolonged steam whistle. At the instant it begins, he is startled. He instinctively tries to get away; his hands go to his ears. It is not so much that it is unpleasing, but it forces itself so upon him. The instinctive resistance is a necessary part of it: the man would not be sensible his will was borne down, if he had no self-assertion to be borne down. It is the same when we exert ourselves against outer resistance; except for that resistance we should not have anything upon which to exercise strength. This sense of acting and of being acted upon, which is our sense of the reality of things,—both of outward things and of ourselves,—may be called the sense of Reaction. It does not reside in any one Feeling; it comes upon the breaking of one feeling by another feeling. It essentially involves two things acting upon one another.

Third, let us imagine that our now-awakened dreamer, unable to shut out the piercing sound, jumps up and seeks to make his escape by the door, which we will suppose had been blown to with a bang just as the whistle commenced. But the instant our man opens the door let us say the whistle ceases. Much rel...