![]()

1

Fundamento

* Umi *

Batá drumming is used to support Afro-Cuban Santería. Santería is a “danced religion” based on Yoruba religious concepts disguised under and influenced by Catholic ideology and symbols. The foundation of Santería was established during the colonial period; subsequent developments in Cuba and other reaches of the diaspora, like California, are evolutions from this base. The original development began with the increased importation of enslaved Africans after 1762, when the British briefly occupied the island and opened it to trade more than ever before. The development of Santería took of even more in the early decades of the nineteenth century, when Cuba moved to replace Haiti (whose economy was destroyed by the only slave revolt to establish a black nation in the Americas) as the world's largest sugar producer. To do so Spanish Cuban planters brought more African labor to work the cane fields and refining machinery. Concurrent civil strife among the several Yoruba groups of West Africa resulted in even more enslaved.

YORUBA IN CUBA

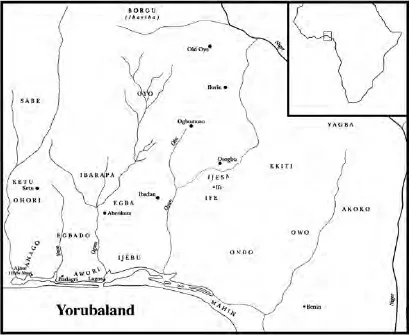

Large numbers of Yoruba from all ranks of society arrived in Cuba at a time when slave care (lodging, etc.) improved and a fairly even ratio of male to female as well as old to young Africans was established.1 Their arrival also coincided with the last decades of slavery, which was abolished in Cuba by 1886. For example, from 1850 to 1870, Yoruba subgroups such as the Egba, Ijesa, Ijebu, and Oyo formed one third of all the enslaved Africans brought to Cuba. Like Salvador da Bahia (Brazil), during much of the nineteenth century Havana could be considered a Yoruba city in the Americas.2 This situation positioned the Yoruba to preserve their own lifestyle (religion, music, etc.) and to mark Cuban culture in unique ways. The experience of the Yoruba in Cuba exemplifies both continuity with Old World African traditions and innovation in response to New World conditions.

Whereas in Yorubaland each subgroup had only self-identified with a local community, in Cuba they gradually developed a wider shared identity. They became an ethnic “nation” (nación) alongside, although distinct from, other “nations” of related yet diverse peoples who founded new, common identities in Cuba.3 In Yoruba language “olukumi” means “my friend”; as colonial officials heard this greeting they began to identify the Africans who used it by the same term. So it is that the name for the Yoruba nation in Cuba became Lucumí.

Lucumí ethnic identity in Cuba is closely related to Yoruba culture from Africa and forms one of the main bases for the Santería religion. Some people refer to Santería as “Lucumí religion” or “Lucumí.” Santería is dominated by Yoruba traits and the ritual language used in Santería prayers, chants, and songs is dominated by Yoruba vocabulary and Yoruba phonetic and syntactic structures.4 There has been influence from Catholicism and Kardecian Spiritism, but the foundation is Yoruba. “Fundamento” means the root of Lucumí identity, which first developed in nineteenth-century Cuba. It has inherent power, which is passed down from generation to generation through various ritual objects, social organizations, and activities. The crafted and consecrated batá themselves, groups of batá drummers and associated lineages, and communal religious celebrations with music are examples. Based on fundamento, the national ethnic designation of Lucumí came to describe distinct language, cultural attributes, physical characteristics, and ways of behaving. Like Carlos, many in Cuba are direct descendants of Yoruba.

At the same time, those who were not Yoruba by blood could become part of the Lucumí “nation.” The gradual disappearance of African-born blacks in Cuba after slave importations ceased, intermarriage across ethnic groups, and religious conversion of non-Yoruba and even white Cubans forced the tradition to expand or perish.5 Te Lucumí “nation” became detached from the ethnic group that had developed it and took on a life of its own.6 Being Lucumí “began to rest less on [one's] ethnic descent…than on the spiritual path [one] followed.”7 This greater inclusiveness allowed Lucumí tradition to survive and to this day facilitates its spread. People in several locations around the world, with and without connections of family descent, consider themselves to be “Yoruba.” In Nigeria, the batá drum is an important symbol of Yoruba identity. Fittingly, the Afro-Cuban batá tradition as described by Carlos Aldama is one of the most powerful markers of Yoruba-Lucumí identity in Cuba and everywhere it has spread.

Regions throughout Yorubaland reflect the various subgroups that together founded the Lucumí nation in Cuba. The city of Old Oyo in the north was the seat of the Yoruba Empire. Prepared by Barbara Beckmeyer, Lark Simmons, and the author, 2010.

The Lucumí of Cuba are part of what anthropologist J. Lorand Matory has called the Yoruba Diaspora. He contends that the Yoruba Diaspora consists of all the peoples that practice Yoruba-derived culture. Communities in different regions like Nigeria, Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the United States share common historical and spiritual roots. Furthermore, these communities are aware of and influence each other's religious practices.8 Edwards and Mason list ten basic beliefs of the Yoruba, which apply to Santería and provide a backdrop for Carlos's stories. The Yoruba believe:

1. There is one God who created and controls the universe and all that is contained therein.

2. There are selected forces of nature called

òrìà9 that deal with the affairs of mankind on Earth and govern the universe in general.

3. The spirit of man lives on after death and can reincarnate back into the world of men.

4. Ancestor spirits have power over those who remain on Earth, and so must be remembered, appeased, honored, and consulted by the living.

5. In divination.

6. In the use of offerings and blood sacrifice to elevate their prayers to the oricha and the ancestors [eggun].

7. In magic.

8. In the magical and medicinal use of herbs.

9. Ritual song and dance are mandatory in the worship of God.

10. Humankind can commune with God through the vehicle of trance possession.10

The oricha are specific forces of nature, selected to exist within God, which govern different parts of the universe. The deities are associated with forces of nature, such as wind, volcanoes, iron, oceans, and rivers. Oricha that will be addressed later include Eleguá, the oricha of the crossroads and decisions; Ogun, the warrior and ironsmith; Ochosi, the hunter and marksman; Changó, king of the drum and dance; Obatalá, oricha of wisdom and peace; Oyá, warrior woman who controls the wind and the cemetery; Yemayá, goddess of the sea, mother of all; Ochun, oricha of sensuality, creativity, and fertility; and Orula, diviner par excellence.11 Beyond their distinct symbolic representations, the oricha are fountains of vital spiritual energy that rejuvenate, sustain, and regulate the community. Santería is also referred to as La Regla de Ocha (The Law of the Oricha).

In Yorubaland Àyàn or Àyòn is the oricha of drums. In Cuba it is spelled Añá, yet pronounced exactly as it would be in Yorubaland. It is also the name of the African Satinwood tree,

Distemonanthus, used to construct drums,

àngó dance clubs, house posts, and sometimes canoes.

12 Añá, the godly energy that inhabits the drums, can be described as the Spirit of Sound that is able to invoke the deities and stir all the human emotions. In Yorubaland, Añá family lineages pass on performance and ritual knowledge from father to son.

13 In Cuba, the transmission by family lineage did not survive slavery and was replaced by batteries or groups of drummers led by a master drummer patriarch. As in Yoruba-land, the father/teacher transmits his knowledge to and confers some of his status upon the son/apprentice.

Batá drums that possess Añá are said “to have fundamento” or “to be de fundamento,” meaning of or from the foundation. This translation of a Yoruba concept into Spanish underscores the association of batá with the core of Lucumí identity. According to Cuban Añá tradition, sacred batá must be “born” from a previously consecrated set of drums. This is how the “voice” of Añá is transmitted, allowing a new set of batá to talk to the oricha. The older set of drums becomes the “godfather” (padrino) of the new set, and so lineages or families of drums arise. Batá drummers rely on these lineages to establish the religious credentials of their drums.14

In Cuba, the term that was coined for unconsecrated batá is aberikulá (abèrínkùlá), which literally means “the ridiculer rumbling splits open,” or to burst one's sides laughing. It is a term of derision. Before 1976 all batá played in the United States were unconsecrated, a survival necessity that blunted the sense of sharp criticism that the term implied in Cuba. In both Cuba and the United States today, batá that are aberikulá are still used when the patron cannot afford to hire a drum battery that possesses Añá.15 Another name for unconsecrated batá in Cuba is tambor judío, or Jewish drum. The term was used by Lucumí drummers in the context of a colonial society dominated by Catholicism to signal unorthodoxy and a pejorative sense of difference. Drummers in the United States almost never use this term. As Carlos and I got to know each other, he would at first only invite me to play when a tambor aberikulá was being given. The stakes were not as high. Only later, after we became friends and he felt confident enough in my drumming, did he ever invite me to play at a tambor de fundamento.

“Santería” means the way of the saints (santos), which are none other than the Yoruba oricha that were masked in order to keep the tradition in the hostile context of slavery. In order to appease Catholic missionaries, enslaved Yoruba found similarities between oricha and saints, and while appearing to worship the saints continued to worship the oricha. Also, as the African sensibility is more open than closed to new religious influences, they may have actually devoted sincere spiritual energy to these Catholic survival adaptations. When Carlos Aldama speaks of fundamento, oricha, Añá, aberikulá, and even fiesta (see below and glossary), he is using his Yoruba head.16 In doing so he illuminates an Afro-Cuban world shaped by Yoruba culture in diaspora.

One of the most important social spaces where Lucumí identity, Santería, and batá flourished was the cabildo. The cabildo tradition came to Cuba from Seville, Spain, and was aimed at organizing social classes on the basis of mutual aid and religion.17 In Cuba they specifically functioned to organize, receive, orient, and regulate Africans who were brought to the island according to various ethnic groups or “nations,” such as the Yoruba-Lucumí. Distinct ethnic groups formed separate cabildos. Cabildos were institutions of social control that ultimately facilitated African cultural continuity. Located at the bottom of the social order, the cabildos gave the only opportunity (or at least one of the few) for blacks in the Spanish world to organize, whether in Seville or Havana. In Cuba, the cabildos “became indisputably the melting pot that enabled the cosmogonies, languages, musics, songs, and dances related to those systems of worship to preserve their life and signifcance.”18 Many scholars consider that cabildos “incontestably form the starting point for African Santería in Cuba.”19

Cabildos were the principle organizations for the religious life of Afro-Cubans up until the twentieth century.20 By this time, cabildos, though not uniform, held several elements in common: they claimed old African ex-slaves as founders, Catholic patrons, their corresponding iconographic banderas (banners), and saintly devotions enshrined in decorative capillas (altars), legalized reglamentos (constitutions), mutual aid functions, dual administrative and sacred hierarchies, dues-paying memberships, and double Catholic and Lucumí liturgical regimens and festival cycles.21 Changó Tedún or Changó De Dun (Changó arrives with a roar)22 in Havana was arguably the most widely known and important Lucumí cabildo in Cuba's history.23 In 1900, reincarnated as the Cabildo Africano Lucumí, it celebrated the annual feast day of its Catholic patron, Santa Bárbara, on December 4 with a Catholic mass, a formal procession afterward, and batá drumming for Changó.24 The history of the Lucumí cabildos mirrors the transformation of the Lucumí ethnic identity itself. Over time cabildos became socio-religious societies of mixed ethnic and racial composition, whose diverse members practiced what was emerging as La Regla de Ocha or Santería. Many batá drums were built and consecrated for use within specific cabildos. Much of Carlos's experience as a batalero was gained, for example, in the annual procession put on by a famous cabildo in Regla.

“Oricha houses” or ilé oricha were born out of the cabildos and developed as more independent centers of socialization and Lucumí ritual practice. Each ilé oricha is made up of a lead priest or priestess and his or her following of younger priests initiated within the house as well as non-initiated apprentices and believers. Currently in Cuba and the United States, the oricha house is the main unit of communal observance. Within them, believers “become” Lucumí through initiation into the priesthoods of the various oricha. Ilé oricha are the main sponsors of the batá because they hire drummers and drums to support important ceremonies with music.

The batá drum tradition is classical music: its repertoire has order, balance, and restraint, while conforming to an established and elaborated art form of historical significance. Yoruba (Nigerian) and Cuban musicians acknowledge batá tradition as the authentic authority in expressing core religious values within Yoruba-derived culture. Each drum rhythm is associated with a particular oricha or spiritual entity and many rhythms are played in a liturgical order as a ceremonial blessing in honor of all the oricha, but also for the faithful worshipping community. Each worshipper is connected to several oricha and thereby to several rhythms as part of the tradition. Carlos, for example, is related to Changó and Ochun, his spiritual “father” and “mother.” I am connected most closely to Ochun and Eleguá.

Throughout the book, Carlos refers to an individual batá rhythm as a “tambor” or as a “toque.” In addition to any particular rhythm played with the batá, tambor refers to the batá drum itself as well as to the ritual-musical gathering where batá rhythms praise and invoke the oricha. When Carlos uses the word toque, he means a rhythm played with the batá, or the ritual-musical gathering where this takes place, but not the batá drum. The overlapping of some terms emphasizes the fact that in Afro-Cuban culture, as in many cultures of the African Diaspora, social gatherings are...