- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

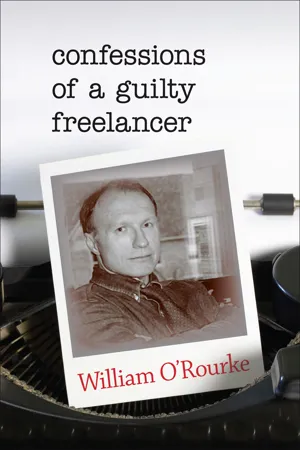

Confessions of a Guilty Freelancer

About this book

From an acclaimed writer and journalist, essays containing "a brilliant overview of American history from the 1960s to the post 9/11 era" (Maura Stanton, author of

Immortal Sofa: Poems by Maura Stanton).

William O'Rourke's singular view of American life over the past 40 years shines forth in these short essays on subjects personal, political, and literary, which reveal a man of keen intellect and wide-ranging interests. They embrace everything from the state of the nation after 9/11 to the author's encounter with rap, from the masterminds of political makeovers to the rich variety of contemporary American writing. His reviews illuminate both the books themselves and the times in which we live, and his personal reflections engage even the most fearful events with a special humor and gentle pathos. Readers will find this richly rewarding volume difficult to put down.

"O'Rourke has always had his finger on the pulse of the contemporary American literary scene." —Corinne Demas, author of The Writing Circle

"With sparkling wit that never takes a vacation, [O'Rourke] is our unpaid public intellectual number one." —Jaimy Gordon, author of Lord of Misrule, winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Fiction

"O'Rourke's . . . writing is literary, without a doubt, but his style is conversational, rhythmic and leavened by a dry sense of humor that engage the reader on an intimate level." — South Bend Tribune

"[T]hose who enjoy a good romp through some of our country's most pivotal times in the company of an astute observer who is unafraid to offer a penetrating, and sometimes scathing, critique of the state of the nation, will find themselves well matched." — ForeWord Reviews

"O'Rourke's descriptions of the writing life have the ring of absolute truth." — Review of Contemporary Fiction

William O'Rourke's singular view of American life over the past 40 years shines forth in these short essays on subjects personal, political, and literary, which reveal a man of keen intellect and wide-ranging interests. They embrace everything from the state of the nation after 9/11 to the author's encounter with rap, from the masterminds of political makeovers to the rich variety of contemporary American writing. His reviews illuminate both the books themselves and the times in which we live, and his personal reflections engage even the most fearful events with a special humor and gentle pathos. Readers will find this richly rewarding volume difficult to put down.

"O'Rourke has always had his finger on the pulse of the contemporary American literary scene." —Corinne Demas, author of The Writing Circle

"With sparkling wit that never takes a vacation, [O'Rourke] is our unpaid public intellectual number one." —Jaimy Gordon, author of Lord of Misrule, winner of the 2010 National Book Award for Fiction

"O'Rourke's . . . writing is literary, without a doubt, but his style is conversational, rhythmic and leavened by a dry sense of humor that engage the reader on an intimate level." — South Bend Tribune

"[T]hose who enjoy a good romp through some of our country's most pivotal times in the company of an astute observer who is unafraid to offer a penetrating, and sometimes scathing, critique of the state of the nation, will find themselves well matched." — ForeWord Reviews

"O'Rourke's descriptions of the writing life have the ring of absolute truth." — Review of Contemporary Fiction

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Confessions of a Guilty Freelancer by William O'Rourke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

confessions of a guilty freelancer

part one

the personal

Here’s Mine

I was home in South Bend, Indiana, in my attic office, working on a novel involving coal miners, set against the backdrop of the 1984–85 National Union of Miners strike in England. The phone rang and it was Eric Sandeen, the oldest child of my friends, Eileen and Ernie Sandeen. Eric, a professor of American Studies at the University of Wyoming, was in town to go to the Notre Dame-University of Southern California football game. His father was an emeritus professor of English at the university and Eric was using his tickets. And he had an extra one for the game that was to start in about an hour, which he offered to me. I had donated my tickets to some good cause. It was October 26th, 1991, and the fall weather was only fair: but the gray, overcast sky wasn’t supposed to turn into rain.

My day’s work writing was about over, in any case: the cold, wet atmosphere of the novel’s English pit towns had seeped into me and the idea of getting outside was appealing. My novel, for a number of reasons, had been hard going. I decided to abandon it and attend the game.

I went downstairs and told my wife I was leaving. She was working at her computer, preparing testimony for an appearance as an expert witness (she is an economist) and looked at me skeptically, but bid me adieu. She said, “I’m so worried about Monday my heart hurts.”

Our fifteen-month-old, Joe, was downstairs with a babysitter, whom we had retained for three hours, so both my wife and I could get some work done. Eric was impatient to get into the stadium (he was an alum and wanted to bask in the pre-game show), so I was rushing to get there so as not to delay him any further.

The coal miners of Great Britain would have to wait. I said goodbye to everyone in the house and took off. What going to the game meant was that Teresa would have to take care of Joe by herself after Maria, the babysitter, left. I had planned to watch the game on television, which would have left me able to look after Joe. We were attempting to divide looking after our boy fifty-fifty, which amounted in these modern arrangements to doing it seventy-five-seventy-five. Teresa’s father had been an all-American football player at Berkeley, but she was not a fan. Football was the bane of fall weekends for her as a new mother, just as it was when she was a young girl.

We lived near the campus, but on a football weekend the university becomes a sports franchise and for me get to the closest parking available required a circuitous route, through South Bend’s downtown and then approaching the campus obliquely from the south, parking in a poor neighborhood adjacent to the campus.

South Bend isn’t a college town and the university always has been separate from it, especially back in the heyday of the town, when the Studebaker car company was the city’s biggest employer. But now Notre Dame is the largest employer and, though the campus is still on its edge, it is central to the business interests here. I parked my old Volvo near Notre Dame Avenue, by the first house I owned when I first moved to the town, about six blocks from campus.

It is a neighborhood of student rentals and African American households, and a few junior faculty, which is what I had been when I lived there. Notre Dame Avenue is a wide street that goes straight into the heart of the campus. It is wide because there are railroad tracks beneath layers of asphalt, tracks of the South Shore Railroad, since in the halcyon days of the midcentury, the era of Ronald Reagan as the Gipper, the South Shore Line used to come into the campus, as well as going straight through the middle of downtown South Bend.

After parking, I walked quickly to the stadium. It was about a half-hour before kickoff. There were stragglers on the periphery of the campus, but most of the 60,000 people were either in or around the stadium, tailgating in the pay parking lots, swarming around the brick edges of the stadium like ants around a morsel. I met Eric beneath the entrance he specified and he gave me a ticket. It was a good seat, better than my own season tickets provided.

Eric rushed in and I told him I’d join him after I got something at the concession stand. I hadn’t eaten lunch, so I wanted a hot dog. I stood in line, put in my order for a Polish kielbasa, the thicker sort of hot dog, and a Diet Coke.

As I walked away with my refreshments I felt something peculiar. It was so strange it stopped me mid-step. I was forty-five years old and I had felt many things, but never before this particular feeling: I felt a click deep inside. The image the sensation produced in my mind was of a BB, a small round piece of copper-colored lead, falling into a socket. It was a very clear image. A BB is tiny, but the one I imagined felt infinitesimal, microscopic. Yet I felt it, a click, metal on metal. Like an expensive, microscopic gear had slipped, some exquisite piece of machinery falling out of alignment. Some medieval example of craftsmanship, a gyroscope, something intricate, needing fine balance. The feeling, the event, was located in my chest, below my left breast. It was thoroughly interior, as if a signal had been sent and registered, what those giant satellite dishes are poised waiting for, a transmission from deep space.

I continued on into the stadium to find my seat and join Eric. They were great seats, practically on the fifty-yard line. And they were real seats, with backs, not just a slab of lumber to sit on as I was used to, and we were only a few rows from the field.

The seat was so good someone was sitting in it. A woman, it turned out, who had misread her ticket’s row number. After she moved I sat down and thought about eating my large hot dog. But I began to feel sick to my stomach. Since I hadn’t eaten for a few hours I couldn’t understand why. But I did feel nauseous. So much so I put my head between my legs to bring myself some comfort, to get some blood to my head, I supposed. Then I felt something electric, part tingle, part buzz, traveling down through my left arm.

I’m not sure how long I was bent over. I heard Eric say something along the lines of, “Are you all right?”

I replied, “I’m not sure.” I began to feel cold and clammy.

I jerked myself up. It seemed that the temperature had dropped thirty degrees. My shoulders were up and my neck compressed down as if I was freezing. The electric feeling in my arm was creeping up my shoulder into my neck. I felt sweaty. I looked at my right hand. It was blazingly white. My left hand still had the hot dog in it. I put the hot dog in the pocket of my coat.

I heard Eric then say, from what sounded like a long way away, “Do you think it has to do with your heart?” I heard that, but I didn’t react to it. It was as if I saw someone I thought I knew, but couldn’t actually remember who it was. The question just hung there.

I am not sure how much time had passed. Three minutes? Five? But it took me at least that long to admit to myself what was going on. I was having a heart attack. I had read and heard the list of symptoms enough times. It seemed a classic case: nausea, tingling in the arm, sweat, the tightness of my neck and shoulders. I considered none of it pain: I had been hurtled forward into another state, one I had never been in, as if I was in outer space without a suit.

I knew there was a first aid station in the stadium. I needed to get there, but I didn’t know where it was located in relation to these unfamiliar seats. I looked about and there seemed to be a mist in the stadium: a fog – one that transmitted color. Some USC players were on the field in front of me. They moved slowly, silently. The gold and red of their uniforms glowed incandescently.

I swung my head back around and looked for an usher. He would know. I told Eric I was going to the first aid station and I heard him get up behind me. There, at the end of the row, was a frail old man with an usher’s cap on. “He must be near ninety,” I thought. I asked him where the first aid station was and he looked at me with concern, took my arm, and led me through a tunnel to the concourse below the stands. This was familiar. I did not resist his help, though I thought it must look strange, a man twice my age helping me along. People parted before us, rubbernecking pedestrians, most staring with curiosity and alarm. Just who looked older or frailer at that moment, me or the usher, I cannot say.

Even in my distress, I thought us a strange sight, though I had seen one dying person walking before. It was 1981 and I was visiting my closest friends, Robert and Inez Kareka in Boston, right before I came out to the Midwest to start teaching at Notre Dame.

Inez had been fighting cancer for two years and her battle was almost over. In the middle of the night noise had awakened me. I saw Robert helping Inez to the bathroom. She had been asleep in the living room and had opened the refrigerator door, thinking it was the bathroom and had backed into it, crashing its contents. He was leading Inez to the actual bathroom and she looked transformed; she was in her late fifties then and had always been a looker, in the style of Marilyn Monroe, from whose generation she was.

But that night her dyed blonde hair was wildly askew. Her hair’s black roots framed her thinned face, her now stick-like limbs were held akimbo, and her expression was fixed in a muted scream, as if she wanted to say something but had lost the language to do so. She looked exactly like an eighteenth-century engraving of death I had seen. And that morning she went into a coma she never came out of until she died a week later.

In the stadium, dragging my legs and waving arms as I walked along with the ancient usher I thought I, too, must look like death.

We got to the door of the first aid station and, upon entering, the silence that had seemed to surround me vanished. There was a TV on tuned to the pre-game show. People were animated, talking. Eric stayed by the door.

“Is there a doctor here?” I asked. A few people in the room came toward me quickly. “Here, get his coat off.” I was wearing an expensive Barbour coat I had bought in England. It had the hot dog in the pocket. I sat down and someone began to unbutton my shirt. Another hand had grabbed my wrist and I heard a voice say, “I can’t find a pulse.”

He said it to a slightly older man, but not that much older than me. “Oh, you’re probably just hyperventilating,” the man, who was addressed, said.

“He must be the doctor,” I thought. “I’m a professor here,” I said, “I’ve taught for over ten years and I’ve never hyperventilated in my life. If I’m hyperventilating, put a bag over my head.”

No one was going to say what was obvious: I was having a heart attack. Not even me. But I did feel better saying something forceful; that I had some force. Eric (who is very tall) was looming by the doorway. The doctor said, “We’ll get you to the hospital just to be safe.” There was more motion around the room.

Eric said something about him going to the hospital and I said, “No, stay, enjoy the game.” He had come a long way to go to the game. I thought I heard him say he would call Teresa.

My shirt hung, unbuttoned, loose around me. My coat was gone. A gurney was produced near the doorway and I was led to it and helped up to lie down on it. Straps were put over me and I was wheeled down the concourse. I was now staring upward and would see the occasional face looking down at me, again with a mixture of alarm, curiosity and concern. I was a spectacle. The game hadn’t yet begun. An ambulance was parked near one of the stadium’s gates. I had seen it there before and took little notice. The gurney’s legs were collapsed and it was picked up by two men wearing similar coats and rolled into the ambulance. One of the men hopped into the ambulance’s narrow cabin and began to attempt to put an intravenous line into the skin above my left hand. They wanted to drip something in. He kept sticking me, trying to get a good purchase on a vein, but seemed not to be having much luck. His attempts didn’t hurt. I seemed to have a surface numbness. I was just unhappy he wasn’t succeeding. It seemed like a lot of time was passing and nothing was going on. Finally, he stopped trying and left the needle inserted in whatever fashion it was and taped it. More minutes seemed to pass and finally the doors of the ambulance closed.

I could picture where the ambulance was going, after it finally started to move. Though I was wearing a watch, I wasn’t looking at it to check how much time had passed. Time was both elongated and slowed. Here was the now; I was in it. The ambulance needed to part the waters; there were still crowds around the stadium and there was no direct way out. It twisted and turned and finally I felt it speed up as it hit city streets. It turned out they were going straight up Notre Dame Avenue. Lying down on the gurney I was a mass of resistance; my shoulders continued to rise as my neck and head attempted to retract into my body, turtle-like. The sensation in my arm and neck was no longer an electrical buzz; it was molecular, an ethereal feeling, as if I was being transported somewhere – and not just my body being ferried in an ambulance. Its siren was on, but it didn’t seem loud. Turning my head, I saw the roof of my former house go by; here, literally, was my life passing by. But what I was feeling was being erased. As if I was a stone on the surface of the water, about to be swallowed over, ripple-less. I felt, as clearly as I have ever felt anything, how everything in the world would go on without me.

Here and gone. Gone gone gone. Then, what I knew surfaced, how this ride up the empty street (because of the game there was no traffic on it) was so much like all the mythology I had ever read: Lethe, the river Styx, the voyage across, death’s boatman, Charon at the wheel, the trip to Elysium. In the eerie quiet of the ambulance I was being taken away. Away. The ferrymen were riding up front. I was alone.

We arrived at the hospital. Doors opened and I was rolled out and in, ending up in an examining room, one of the ambulance attendants carrying the drip that he had attempted to hook up to me. I heard him say to a nurse he didn’t think it was right. I was still on my back. A nurse took my hand and prepared another intravenous line. She left the one he put in in. Another drip was started through the new one.

Someone asked, “Are you from out of town?”

It seemed an odd question. Beyond the drip that had been started, nothing was happening. I was prone, making sounds that were between language and a moan.

I thought then of what they were looking at: a short, overweight, white male, in his mid-forties, with thinning hair, without a prosperous-looking face. I was wearing old work shoes, from Sears Roebuck with “Die Hard”(!) embossed on their soles. My khaki pants were close to twenty years old, as was the old, worn leather belt. The flannel shirt hanging loosely on me, though not twenty years old, was frayed and old enough.

“I’m a professor at Notre Dame,” I said weakly.

I didn’t hear a harrumph, but no one said anything. There continued to be some milling about. I lay there thinking someone should be doing something.

“I’m a professor at Notre Dame,” I repeated more forcefully to no discernible affect.

Time passed. “Too much time,” I thought, and, with some difficulty, I got myself to sit up. With my right arm and hand, the one that wasn’t singing with molecular activity and didn’t have a drip inserted into it, I awkwardly fished for my wallet. I laid it open on my thigh, and slowly thumbed through the contents until I found the thin and shiny Blue Cross card. I waved it above my head.

“Here’s my insurance card,” I proclaimed.

It was snatched from my hand and the room was immediately transformed into a beehive of activity. My shirt was removed, and an oxygen necklace was draped around my face. I was given nitroglycerin to take under my tongue, and someone appeared with a clipboard to take more information. Questions were asked, names, addresses. An EKG machine was wheeled in, and I was hooked up to it. An intravenous line was inserted into my other hand.

I realized that had I been wearing my English Barbour jacket, someone would have recognized it as the costly thing it was, and made some judgment other than that I might be a derelict. I felt whatever had caused the inactivity was my appearance; I did not appear to be a man of substance until I produced my Blue Cross card.

Finally, someone I took to be a doctor came into the room...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Part 1 The Personal

- Part 2 The Personal and the Political

- Part 3 The Personal and the Political and the Literary

- Acknowledgments

- Index