- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Objects that make the past feel real, from a stone axe head to a piece of John Brown's scaffold—includes photos.

History isn't just about abstract "isms"—it's the story of real events that happened to real people. In Touching America's History, Meredith Mason Brown uses a collection of such objects, drawing from his own family's heirlooms, to summon up major developments in America's history.

The objects range in date from a Pequot stone axe head, probably made before the Pequot War in 1637, to the western novel Dwight Eisenhower was reading while waiting for the weather to clear so the Normandy Invasion could begin, to a piece of a toilet bowl found in the bombed-out wreckage of Hitler's home in 1945. Among the other historically evocative items are a Kentucky rifle carried by Col. John Floyd, killed by Indians in 1783; a letter from George Washington explaining why he will not be able to attend the Constitutional Convention; shavings from the scaffold on which John Brown was hanged; a pistol belonging to Gen. William Preston, in whose arms Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston bled to death after being shot at the Battle of Shiloh; and the records of a court-martial for the killing by an American officer of a Filipino captive during the Philippine War. Together, these objects call to mind nothing less than the birth, growth, and shaping of what is now America.

"Clearly written, buttressed by maps and portraits, Brown's book regales while showing the objectivity and nuance of a historian."— Library Journal

"A whole new way of doing history…a novel form of story-telling."—Joseph J. Ellis, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation

History isn't just about abstract "isms"—it's the story of real events that happened to real people. In Touching America's History, Meredith Mason Brown uses a collection of such objects, drawing from his own family's heirlooms, to summon up major developments in America's history.

The objects range in date from a Pequot stone axe head, probably made before the Pequot War in 1637, to the western novel Dwight Eisenhower was reading while waiting for the weather to clear so the Normandy Invasion could begin, to a piece of a toilet bowl found in the bombed-out wreckage of Hitler's home in 1945. Among the other historically evocative items are a Kentucky rifle carried by Col. John Floyd, killed by Indians in 1783; a letter from George Washington explaining why he will not be able to attend the Constitutional Convention; shavings from the scaffold on which John Brown was hanged; a pistol belonging to Gen. William Preston, in whose arms Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston bled to death after being shot at the Battle of Shiloh; and the records of a court-martial for the killing by an American officer of a Filipino captive during the Philippine War. Together, these objects call to mind nothing less than the birth, growth, and shaping of what is now America.

"Clearly written, buttressed by maps and portraits, Brown's book regales while showing the objectivity and nuance of a historian."— Library Journal

"A whole new way of doing history…a novel form of story-telling."—Joseph J. Ellis, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Touching America's History by Meredith Mason Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Museum Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Axe Head, Adze Head: The Pequot War

Most of the relics I inherited or were given to me or to my brother. The only ones I bought were a stone axe head and a stone adze head—both bought in Stonington, Connecticut, where I live—the adze head from a local antique dealer, the axe head at an antique fair in the gym of a local school (see figure 1.1). I was told both were found around Stonington—in Groton, Noank, or Mystic, which is entirely likely. They match nicely with pictures of axe heads and adzes from pre-Mayflower New England. Dr. Kevin A. McBride, director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, who directs all archeological excavations and ethnohistorical research for the Pequot, after hefting the axe head and adze head, told me that if they came from Mystic or Noank, it was likely the Pequot made them, because Pequots had been in that area for hundreds of years before the English arrived in the area—although he also said many tribes made similar objects and had been doing so for thousands of years.1

Both of my tool heads were finished by polishing rather than flaking. The adze head is of light gray stone, about seven inches long, a little over two inches wide, less than two inches thick at its thickest. It’s flat on the bottom of its length, where it would have been lashed to the top of a wooden handle, and gently curved on the top. A book of Algonquian tools said such an adze would have been used for stripping bark from trees, and Dr. McBride agreed that this was a likely use, as was hollowing out dugout canoes. My adze head has a good weight and feel for these uses.

Fig. 1.1. Stone axe and adze head. Author’s collection.

The axe head is of a denser, darker gray (almost black) stone than the adze head. I guessed the stone was basalt; Dr. McBride confirmed this, adding that although basalt was not in our immediate neighborhood there was a vein up near Hartford, and basalt from there was traded into Pequot country. The axe head is six inches long, three inches wide, and two inches thick at its thickest. The back of the head is rounded; the front slopes on both faces to an edge. The stone is girdled at its thickest by a groove the width of your forefinger, for hafting. It weighs a little over two pounds. One side is more finely polished than the other. Some chips have been knocked off the front edge. One good-sized chip is missing from the back of the head, which would have been used like a hammerhead.

The Algonquian tribes who lived near or not far from Stonington before the English came were the Pequot, the Nehantic, and the Narragansett. The Nehantic and, to the east of them, the Narragansett may have been in the Stonington area before the Pequot. There is some support for the idea that perhaps around about the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Pequot and their kinsmen the Mohegan pushed into southeastern Connecticut from the center of Connecticut. Some believe they came from the Hudson River Valley and that they were possibly related to the similar-sounding Mahican. Others doubt this, pointing out that Mohegan or Mahican simply means “People of the River” in Algonquian languages, and that the Mohegan and Mahican languages are not very closely related.2 Dr. McBride believes the idea of a fairly recent Pequot intrusion into the area is a baseless nineteenth-century hypothesis, which may have been put forward to help justify the white settlers’ fights against the Pequot. In any event, the Mohegans and Pequot settled along the Thames and Mystic rivers. In the 1620s, the Pequot defeated other tribes and gained control of trade on the lower Connecticut River. By 1630, they were also receiving wampum as tribute from eastern Long Island.3 The wampum was important in buying pelts from the Indians of the interior, and the pelts in turn could be used to buy European trade goods.

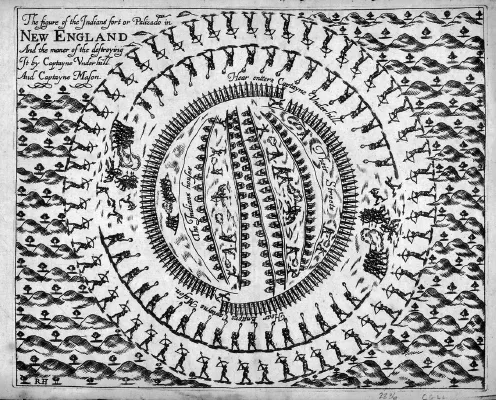

The Pequot fought their neighbors—the Mohegan, the Nehantic, the Narragansett—who fought them back. And in May 1637, five miles from what is now Stonington, where I am writing this, English settlers from the Hartford area and from Massachusetts, together with Mohegan, Narragansett, and Nehantic, killed close to 500 Pequot early one morning after torching their stockaded village on a hill in what is now Mystic, Connecticut. That killing—and the pursuit and scattering and enslavement of the remnant—ended the Pequot as a threat to the white settlers in Connecticut. Not until the opening of Foxwoods Casino in Ledyard in 1992 did the Pequot again become a regional power.

The English had begun to move into Connecticut in the 1630s, settling around Hartford and New Haven and at Saybrook at the mouth of the Connecticut River, although they traded elsewhere. One of the first results of the contacts between the Indians and the Dutch and English traders was a smallpox epidemic in 1633–1634 that probably killed more than half—one estimate is of an 80 percent mortality—of the Pequot. Before European contact, there may have been 13,000 Pequot; just before the Pequot War, that number was about 3,000, a drop of 77 percent.4

Relations between English and Pequot were not always peaceful. In 1633, a trader named John Stone let some Indians come aboard his boat, moored on the Connecticut River. It may be that the trader got drunk. In any event, Stone went to his cabin, fell asleep, and was killed in his bunk, possibly by Western Niantics, a tribe that paid tribute to the Pequot, possibly by Sassacus, a leading Pequot sachem. The Pequot may have killed Stone in reprisal for the Dutch killing in Connecticut of a Pequot sachem named Tatobem, the father of Sassacus.5

In 1635, settlers from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, led by John Winthrop, Jr., son of the colony’s governor, built Fort Saybrook at the mouth of the Connecticut River, challenging both Pequot trade and Dutch efforts to establish a trading post near Hartford. In 1636, John Oldham, a coastal trader from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was killed on Block Island, which had been in the Pequot’s sphere of influence but had come under the sway of the Narragansetts. His death may have been particularly galling to the English settlers because crop failure caused by a huge hurricane in 1635, followed by bitter cold, had left the growing colonies short of food, and Oldham, through his trading, had been an important supplier.6 In August 1636, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in response to the Oldham killing and to the Pequot’s failure to deliver Captain Stone’s killers and the quantity of wampum the Pequot had promised in a 1634 trade treaty, sent soldiers under Captain John Endicott to punish the Indians on Block Island and to raid the Pequot. Endicott burned some villages on Block Island and sailed up the Pequot River (now called the Thames River), destroyed villages and cornfields on both sides of the river, and sailed back to Massachusetts—not having broken the Pequot power but having riled the Pequot mightily.

In 1636, the Pequot attacked stragglers outside the English fort at Saybrook. Two were tortured to death as their companions, huddled for safety in a strong house, heard their screams. A third was roasted alive.7 On April 23, 1637, Pequot raided Wethersfield, a little English settlement, just three years old, south of Hartford. The Pequot burned many of the houses in the settlement. Six men, three women, and twenty cows were killed. Two young women were taken captive. As the raiding Pequot went back down the Connecticut River in three large dugouts, they waved English shirts and smocks they had taken from those they had killed at Wethersfield and shouted at the English garrison at Saybrook, saying that Englishmen were all squaws and their God no more than an insect.8

That did it. On May 1, 1637, the Connecticut General Court commissioned Captain John Mason to lead a force against the Pequot. Mason had been a soldier much of his adult life: with English troops in Flanders before he came to Massachusetts in 1632 and in Massachusetts as a captain of militia, fighting pirates who preyed on commerce in and out of Boston harbor.9 The Connecticut settlers sent 42 men from Hartford, 30 from Windsor, and 18 from Wethersfield. Uncas, the sachem of the Mohegans, added another 60 men to the force. After the death of the Pequot sachem Tatobem, Uncas had tried to become sachem of the Pequot, asserting a claim through his wife’s family. That did not endear Uncas to Tatobem’s son Sassacus, who became the new Pequot sachem and who had driven Uncas and his followers to seek the whites’ protection in the Hartford area.

The force under Captain Mason proceeded down the Connecticut River to Saybrook, where they were joined by nineteen men sent from Massachusetts under the leadership of Captain John Underhill. It was not a large force to send against the several hundred warriors of Sassacus in their hill fort overlooking the Thames River.

Mason and Underhill decided to sail east to Rhode Island to seek support from the Narragansetts. As they sailed along the coast, Pequot on the shore in what is now Groton Long Point spotted them and shouted jeers at them. Seeing that the English had sailed by the mouth of the Thames River, the heart of Pequot power, the Pequot may have concluded that the English and their Mohegan allies had decided not to try their strength against the Pequot.

The Narragansetts, under their sachem Canonicus, furnished about two hundred warriors to the force. More troops were said to be coming from Massachusetts, but Mason was worried about the possibility that the Pequot would hear of the force building on their eastern border and that all element of surprise would be lost. Rather than wait for the Massachusetts reinforcements, Mason and Underhill decided to attack the Pequot—not frontally, up the Thames River to the main Pequot fort in what is now Groton, but by coming on them from behind, by land.

They marched west to the Pawcatuck River, crossed at the ford, and followed the Pequot trail to the Northwest, to Taugwonk Hill, and then down the west bank of the Mystic River, from what is now Old Mystic toward what is now Mystic. But let Captain John Mason tell the story of the attack on the Pequot fort on May 26, 1637, in his own way, speaking of himself in the third person:

And after we had refreshed our Selves with our mean Commons, we Marched about three Miles, and came to a field which had lately been planted with Indian Corn: There we made another Alt, and called our Council, supposing we drew near to the Enemy: and being informed by the Indians that the Enemy had two Forts almost impregnable; but we were not at all Discouraged, but rather Animated, in so much that we were resolved to Assault both their Forts at once. But understanding that one of them was so remote that we could not come up with it before Midnight, though we Marched hard; whereat we were much grieved, chiefly because the greatest and bloodiest Sachem there resided, whose name was Sassacous: We were then constrained, being exceedingly spent in our March with extream Heat and want of necessaries, to accept of the nearest [that is, the fortified village in Mystic, rather than Sassacus’s main fortified village in Groton.]. . . .

We continued our March until about one Hour in the Night: and coming to a little Swamp between two Hills, there we pitched our little Camp. . . . The Night proved Comfortable, being clear and Moon Light: We appointed our Guards and placed our Sentinels at some distance; who hearing the Enemy Singing at the Fort, who continued that Strain until Midnight, with great Insulting and Rejoycing, as we were afterwards informed: They seeing our Pinnaces sail by them some Days before, concluded that we were afraid of them and durst not come near them; the Burthen of their Song tending to that Purpose.

In the Morning, we awaking and seeing it very light, supposing it had been day, and so we might have lost our Opportunity, having purposed to make our assault before Day; rowsed the Men with all expedition, and briefly commended ourselves and our Design to God, thinking immediately to go to the Assault; the Indians shewing us a Path, told us that it led directly to the Fort. We held on our March about two Miles, wondering that we came not to the Fort, and fearing that we might be deluded: But seeing Corn newly planted at the Foot of a great Hill, supposing the Fort was not far off, a Champion Country being round about us; then making a stand, gave the Word for some of the Indians to come up: at length Onkos [Uncas] and one Wequash appeared; We demanded of them, Where was the Fort? They answered On the Top of that Hill: Then we demanded, Where were the Rest of the Indians [i.e., the Mohegans and the Narragansetts]? They answered, Behind, exceedingly afraid: We wished them to tell the rest of their Fellows, That they should by no means Fly, but stand at what distance they pleased, and see whether English Men would now Fight or not. Then Capt. Underhill came up, who Marched in the Rear; and commending ourselves to God, divided our Men: There being two Entrances into the Fort, intending to enter both at once: Captain Mason leading up to that on the North East Side; who approaching within one Rod heard a Dog bark and an Indian crying Owanux! Owanux! which is Englishmen! Englishmen! We called up our Forces with all expedition, gave Fire upon them through the Pallizado; the Indians being in a dead indeed their last Sleep: then we wheeling off fell upon the main Entrance, which was blocked up with Bushes about Breast high, over which the Captain passed, intending to make good the Entrance, encouraging the rest to follow. . . . We had formerly concluded to destroy them by the Sword and save the Plunder.

Whereupon Captain Mason seeing no Indians, entered a wigwam; where he was beset with many Indians, waiting all opportunities to lay Hands on him, but could not prevail. At length William Heydon espying the Breach in the Wigwam, supposing some English might be there, entred; but in his Entrance fell over a dead Indian; but speedily recovering himself, the Indians some fled, others crept under their Beds: The Captain going out of the Wigwam saw many Indians in the Lane or Street, he making towards them, they fled, were pursued to the End of the Lane, where they were met by Edward Pattison, Thomas Barber, with some others; where seven of them were Slain, as they said. The Captain facing about, Marched a slow Pace up the Lane he came down, perceiving himself very much out of Breath; and coming to the other End near the Place where he first entred, saw two Soldiers standing close to the Pallizado with their Swords pointed to the Ground: The Captain told them We should never kill them after that manner: The Captain also said, We must Burn them; and immediately stepping into the Wigwam where he had been before, brought out a Firebrand, and putting it into the Matts with which they were covered, set the Wigwams on Fire . . .; and when it was thoroughly kindled, the Indians ran as Men most dreadfully Amazed.

And indeed such a dreadful Terror did the Almighty let fall upon their Spirits, that they would fly from us and run into the very Flames, where many of them perished. And when the Fort was thoroughly Fired, Command was given that all should fall off and surround the Fort; which was readily attended by all. . . .

The Fire was kindled on the North East Side to windward; which did swiftly over-run the Fort, to the extream amazement of the Enemy, and great Rejoycing of our selves. Some of them climbing to the Top of the Pallizado; others of them running into the very Flames; many of them gathering to windward, lay pelting at us with their Arrows; and we repayed them with our small Shot: Others of the Stoutest issued forth, as we did guess, to the Number of Forty, who perished by the Sword.

Fig. 1.2. Colonists’ attack on the Pequot village, May 1637. From John Underhill, Newes from America (1638). Courtesy of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center.

Captain Underhill, in his account of the burning of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue: History through Things You Can Touch

- 1. Axe Head, Adze Head: The Pequot War

- 2. A Compass, a Rifle, and the Opening of the West

- 3. Yr Most Obt Servt, G. Washington: The Constitutional Convention

- 4. Daguerreotype and Sword: Seminole and Mexican Wars

- 5. Shavings from a Scaffold: The Hanging of John Brown

- 6. Diaries from Indian Country, Civil War Back Home

- 7. Travels of an English Pistol

- 8. A Killing in the Philippines

- 9. An Award from General Pershing

- 10. The Czar of Halfaday Creek and Hitler’s Toilet Bowl

- Afterword: The Shaping of America

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index