eBook - ePub

Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera

Osvaldo Golijov, Kaija Saariaho, John Adams, and Tan Dun

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera

Osvaldo Golijov, Kaija Saariaho, John Adams, and Tan Dun

About this book

Yayoi Uno Everett focuses on four operas that helped shape the careers of the composers Osvaldo Golijov, Kaija Saariaho, John Adams, and Tan Dun, which represent a unique encounter of music and production through what Everett calls "multimodal narrative." Aspects of production design, the mechanics of stagecraft, and their interaction with music and sung texts contribute significantly to the semiotics of operatic storytelling. Everett's study draws on Northrop Frye's theories of myth, Lacanian psychoanalysis via Slavoj Žižek, Linda and Michael Hutcheon's notion of production, and musical semiotics found in Robert Hatten's concept of troping in order to provide original interpretive models for conceptualizing new operatic narratives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera by Yayoi Uno Everett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Musik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Toward a Multimodal Discourse on Opera

“We see shredded strips of blood-red ribbon hanging on his face. Groping, with a blank stare, [Oedipus] stumbles under the scaffolding and ramps that compose the somber stage set, until he is walking knee-deep in a pool of dark water, surrounded by ghostly figures. The chanting of the chorus has come to an end. We watch the water dripping from above, then hear the sound of cleansing pouring rain. The king’s almost primitive self-sacrifice has made him human; Thebes’s plague is brought to an end” (Rothstein 1993). Edward Rothstein’s review of Julie Taymor’s filmic production of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex (1993) vividly describes the theatrical excesses of the concluding scene. This narrative production is a retelling of a myth twice removed; without distorting the essence of Sophocles’ tragedy, Taymor expands the mythical stature of Oedipus by adding new layers to the Ciceronian Latin of Jean Cocteau’s libretto and the neo-classical formality of Stravinsky’s score. Taymor’s mise-en-scène infuses the opera-oratorio with extraordinary power through her deployment of masks and puppets, Oedipus’s dancing double, and extraneous narration in the style of Japanese classical drama. The life-size puppet uncannily mirrors Oedipus’s every gesture, dramatizing the tragic fate of the Theban king.

Taymor’s production of Oedipus Rex is multilayered in the sense that her concept of staging builds additional interpretive layers onto Cocteau’s libretto and Stravinsky’s music from different cultural perspectives. Rothstein argues that the additional cultural layers (e.g., the Butoh dancer, puppets, and clay-covered chorus) transform the mythic elements of the tale by reconfiguring the “primitive energy” of Parisian avant-garde aesthetics into a globalized myth remade for a twenty-first-century audience. I would go further, as does Taymor by claiming that the Japanese narrator’s framing of the opera transforms the oratorio into a hybrid cultural production. Her staging successfully defamiliarizes Cocteau’s avant-garde aesthetics and infuses the ancient myth with rituals taken from Noh drama, Butoh dance, and Indonesian wayang kulit (puppet theater).1 The retelling of the myth in this production is provocative precisely because the cultural references interact without one overpowering the others.

The multiplicity of cultural meanings generated from Taymor’s production of Oedipus Rex has fast become the norm for operatic production rather than the exception. Productions of operas, both old and new, are continually shaped and transformed by new media and aesthetic trends; this view accords with David Levin’s claim that opera has emerged as “an unsettled site of signification,” requiring the audience to attend to a surfeit of competing systems (2007: 3). Each operatic production is unique in the sense that the multimedial elements – music, libretto, film, objects, lighting, mime, and/or dance – operate as interdependent structural and semantic components that shape the narrative production of the whole. Taymor’s Oedipus Rex also calls into question how the production components actively reconfigure the narrative of the initial source material – the libretto and music. So how do we begin to theorize the narrative strategies we bring as viewers and analysts to our holistic engagement with opera? How does our engagement with the production figure into the operatic discourse?

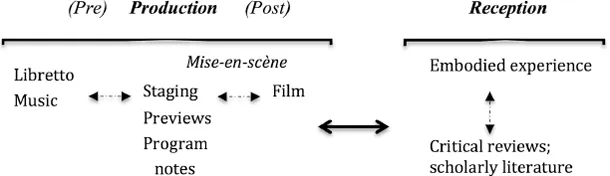

Geoffrey Leech and Michael Short define discourse as “linguistic communication seen as a transaction between speaker and hearer, as an interpersonal activity whose form is determined by its social purpose. Text is linguistic communication seen simply as a message coded in its auditory or visual medium” (Mills 1997: 4). Their definition emphasizes the dialogical aspect of the communication involved; if we assume that both parties share a common knowledge base and interpretive framework (the code, in semiotic terms) for carrying on a dialogue about a particular subject, then discourse is a transaction between the sender and the receiver defined by a particular form (Eco 1976: 49). Operatic discourse is further complicated by multiple and variable factors that shape the communication process between production and reception. Production, in itself, can be divided into pre-production (librettist and composer), production (director, set and lighting designer, and/or choreographer), and post-production (editorial work for filmic version, if relevant). Under reception, we can include the audience’s embodied experience of the performance as well as reviews and scholastic literature that shape our critical response to the work.2 As a music theorist, my investigation typically begins with a close study of the score, libretto, critical commentary, and previews, followed by attending a live production (theatrical or high-definition broadcast) to study the director’s interpretive aims as communicated through the work’s production modes (staging, singing, acting, costumes, props, lighting, etc.). This may be further enriched by interview(s) with the composer, librettist, director, and/or dramaturge. More often than not, the process involves reconciling colliding perspectives; the postmodern staging of a particular work may add new cultural and ideological layers to those of the libretto and music, as exemplified by Taymor’s staging of Stravinsky and Cocteau’s Oedipus Rex.

Taking these variable factors into account, we can construct a dynamic model of musical discourse for the analysis of contemporary operas, as illustrated in figure 1.1. Music and libretto constitute the initial source material at the pre-production stage. With newly commissioned operas, the source material often undergoes change once it enters into the production stage – a portion of the libretto may be omitted or modified and the music may be substantially revised. Under production, mise-en-scène literally means to “put in the scene”; Patrice Pavis defines it as the “concretization of the dramatic text, using actors and the stage space, into a duration that is experienced by the spectators” (1998: 364). In theater, it includes props, scenery, acting, lighting, costumes, and/or music – as shaped by the stage direction. Previews and program notes also fall under production in that their primary function is to communicate the collaborators’ aesthetic intentions to the audience. When a particular production is made available in high-definition broadcast, then released into a film, it belongs to the post-production stage. Mise-en-scène, in this context, includes everything that defines the composition of the shot – rhythm, framing, movement of the camera, lighting, sound, and set design. In lieu of the holistic visual perspective that theater affords the viewer, film shapes the content and form of storytelling through a prescribed sequence of shots and camera angles.

Figure 1.1. A Model for Operatic Discourse

As is frequently the case with new operas, the reception of their premiere informs future production in a circular fashion, as indicated by the bi-directional arrows. In the case of Golijov’s Ainadamar, its 2003 premiere at Tanglewood prompted an extensive revision by Peter Sellars for the Santa Fe production in 2005; its immense popularity led to new productions of the opera by various directors and opera companies between 2007 and 2012. In the case of Tan Dun’s The First Emperor, the critical reception of its Metropolitan Opera premiere in 2006 led to an extensively revised version a year later. Its reception was also marked by a collision of ideologies surrounding the perception of Qin Shi Huang, as will be discussed.

Building onto this audience/analyst-centered model of discourse, I argue that multimodality presents an important basis from which to examine operatic production in its totality. As a starting point, Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen distinguish multimodality from multimedia in the following terms: Multimedia refers to how different physical media (e.g., print, airwaves, radio) are brought together to convey information; multimodality has to do with how we utilize different sensory modes – indexing verbal, visual, and aural resources that are evoked by the media – and the system of choices we use to construct meaning (2001: 67). For my purposes, multimediality will refer to the encoding of media elements from the perspective of production, while multimodality will refer to decoding these elements from an interpreter’s standpoint. Ruth Page, in relating multimodality to the viewer’s construction of narrative, categorizes the multimodal dimensions schematically into textual resources (words, images, sound, movement), platform of delivery (digital screen, printed page, cinema, face-to-face), physical environment (private, public, inside/outside, light/dark), and sensory modalities (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste) (2010: 7). She claims that narratives delivered in different physical environments generate different meanings and bring to light the comprehensive way in which narratives need to be examined in relationship to different modal contexts.

In fact, current research in neuroscience demonstrates that sensory modalities are not processed separately, but in an interactive and integrated manner.3 Alison Gibbons, in her study of the multimodal reading of graphic novels, contends that even if verbal and pictorial recognition occurs in different regions of the brain or neocortex, we construct textual meaning through the co-occurrence of modalities (2010: 100–101). She then explains how the reading of a graphic novel is in itself an embodied activity that relies on a plurality of semiotic modes. For example, she provides a graphic text accompanied by a visual frame from the beginning of Steve Tomasula’s graphic novel VAS: An Opera in Flatland. It contains a boxed and italicized text that reads “first pain,” accompanied by a large starburst shape underneath. Gibbons argues that the reader’s embodied experience is significantly enhanced through the physical sensation of pain evoked by the starburst shape; even in the absence of an agent at the onset of reading, “the visual immediacy of the representation of the paper cut thus induces the reader to envisage the event in relation to the self” (104).

Film composers generate soundtracks to evoke embodied response in viewers through the coordination of sound and moving image. Exaggerated sound effects often accompany action sequences and affect the viewer’s response through a co-occurrence of visual and aural modalities. Think of filmic shots that depict physical violence, where non-diegetic or amplified diegetic sounds are designed to elicit an embodied experience of fright or suspense more vividly in the viewer than if it were evoked by the visual dimension alone.4 Interestingly enough, turning off the soundtrack significantly diminishes the impact. Later in this chapter, I will bring up the concept of intermediality as a framework for illustrating how different media elements depend on and refer to each other in co-articulating the structure of narrative.

In viewing opera, our multimodal experience is further complicated by the multiplicity of elements that shape our embodied experience: text, music, filmic images, choreography, action, lighting, and other production components. As a way to map these elements onto specific categories, I invoke Lars Elleström’s four modalities: 1) material refers to the corporeal interface of the medium (e.g., human bodies, digital screen); 2) sensorial to the physical and mental acts of perceiving the interface through sensory faculties (seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, smelling); 3) spatiotemporal to the structuring of the sensorial perception of the interface with respect to space and time, and 4) semiotic to the creation of meaning in the medium by way of sign interpretation (2010: 35–36). Building on Elleström, I refer to the viewer’s perceptual grouping of media elements according to one or more of the four modal categories as a semiotic field: as an area of signification, each field contributes to the composite sign system with its (integrative) meaning. Our embodied response to a particular operatic scene is typically shaped by the combination of material, sensory, and spatiotemporal modalities of experience. For example, in Peter Sellars’s mise-en-scène for Adams’s Doctor Atomic, the interlude that begins the third scene in Act I depicts a powerful electric storm that threatens the cancellation of the test explosion (DVD #1: 48'47"). Counterpointing the fast, syncopated music with offbeat accents, the strobe light flickers at odd intervals and obscures the view on stage; the workers frantically run from one end of the stage to the other. In lieu of spoken or sung text, the physical and psychological state of panic is registered through the visual semiotic fields in synchrony with Adams’s agitated “filler” music. Listening to the same interlude in the absence of the visual dimension in the 2008 concert setting failed to induce the embodied sensation of “panic” I experienced in watching the DVD or attending Sellars’s staged productions. These somatic effects we experience are by no means trivial. As Elleström explains, the semiotic modality is in effect all along as an integrative device; “the creation of meaning already starts in the unconscious apprehension and arrangement of sense-data perceived by the receptors and it continues in the conscious act of finding relevant connections within the spatial temporal structure of the medium. . . .” (22).

Focusing further on the semiotics of reception, Linda and Michael Hutcheon introduce the concept of multimodal narrative to refer to the embodied action of viewing opera: “the physical move from what theatre semiotician Keir Elam (1980: 8) calls the ‘dramatic texts’ – or the design – to live performance with actual material bodies in actual physical space is an act of narrative production of both the verbal libretto and the musical score” (2010: 66). They argue that, even if the story of Wagner’s Ring cycle is familiar to us, the way it is told defines our multimodal experience. While acknowledging that vocal music is clearly the defining feature of opera, Hutcheon and Hutcheon also emphasize the importance of language, gesture, visual architectural form, color, and other fields as vital components of the multimodal production. Unlike those who claim that the performative mise-en-scène replaces the authors’ printed texts, Hutcheon and Hutcheon argue that production adds to design to the accumulation of meaning(s) and helps “organize the interpretive strategies of the audience members” (67). That is to say, even if the story is already familiar to the audience, the way it is told holistically defines our multimodal narrative experience. They remind us that while no two audience members respond to an operatic performance in the same manner, it is “the task and responsibility of the mise-en-scène to constrain and direct the variety of possible interpretations and responses” (68). The director’s aesthetic intention, indeed, constrains our narrative experience in a definitive manner. This is especially true if the production is converted into a filmic format. The DVD format or high-definition broadcast of a given production establishes a narrative angle through filmic devices (e.g., camera angle, shot sequence) that shape the viewer’s multimodal experience in an entirely different way from attending a live performance of opera in a theater.

To further complicate the picture, Carolyn Abbate defines the narrating voice as marked by “multiple disjunctions” with the music surrounding it, and she emphasizes the fugitive nature of viewing opera as “a rare and peculiar act, a unique moment of performing narration within a surrounding music” (1991: 10). In “Is Music Drastic or Gnostic,” she views performance in real time as a polysemic experience that is fundamentally disconnected from the kind of hypostasized readings that we construct in hindsight, predicated on the notion that sonic media embody expressive signification or contain cultural/poetic associations (2004: 521). Does this necessarily mean that our perception remains provisional and resists being anchored to a fixed interpretation? Yes, if we refer to experience in the moment when we do not perceive something exactly in the same way twice. But if we attend to a particular recording (visual/auditory) of a performance as an artifact for study, the answer is clearly “no.” We form habituated responses to a given work – and more specifically, orga...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Toward a Multimodal Discourse on Opera

- 2. Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar: A Myth of “Wounded” Freedom

- 3. Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater: A Narrative of Trauma and Ambivalence

- 4. John Adams’s Doctor Atomic: A Faustian Parable for the Modern Age?

- 5. The Anti-hero in Tan Dun’s The First Emperor

- Epilogue: Opera as Myth in the Global Age

- Glossary of Terms

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index