![]()

Part I

Schumann and the Piano Virtuosity of the 1830s

During Robert Schumann’s years as an aspiring piano virtuoso, one of the core showpieces in his repertoire was Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 85. Schumann publicly performed the first movement at least once—while a university student in Leipzig, he returned to his home city of Zwickau to play it at an “Evening Concert” on April 28, 1829. The young pianist seems to have delighted in the work and played it masterfully. After Schumann moved to Heidelberg for his law studies, he played the Hummel for his friend Theodore Töpken, who recalled, “I was struck by the aplomb of his playing, by this consciously artistic rendering.” In a letter to Hummel himself, Schumann boasted that he could perform “the A-minor concerto (there is only one) calmly, securely, and without technical mistakes.”1

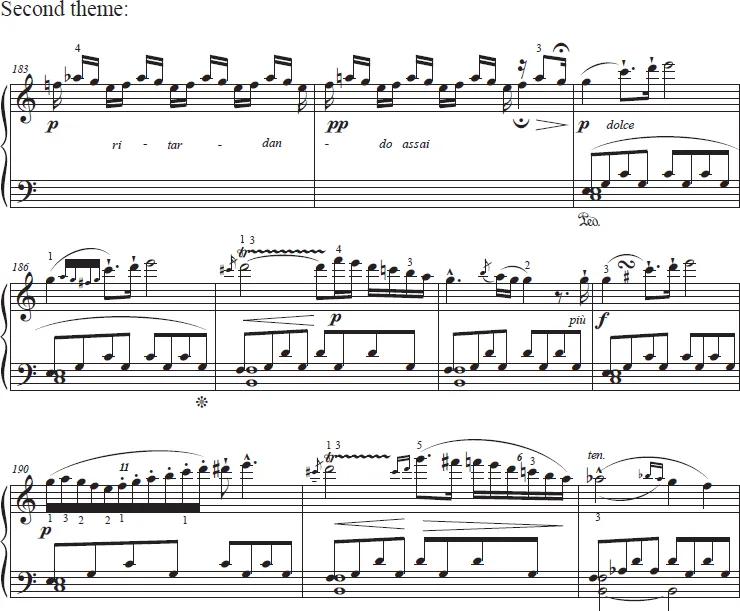

Hummel’s concerto displays the pianist’s skill in a kaleidoscopic range of virtuosic and consistently transparent textures. Example 1.1 provides two excerpts from the first movement’s exposition. Flickering, single-line runs embellish the second theme, varying melodic contours as they recur and enlivening sustained notes. At the end of the exposition, the soloist showers listeners with double notes, arpeggios, and scalar figures. Over the regular stride of the accompaniment, right-hand patterns change every two to four measures. Several times the piano figuration works its way into the uppermost register, climbing toward increasingly bright sounds, only to descend and begin another ascent. Hummel uses stark contrasts to highlight these sections. In its last measures, the transition to the second theme slows and dwindles to a pianissimo. At measure 217 of the expositional close, two measures of alternating neighbor tones momentarily create a dense, closely voiced flurry of chords that the transparent passagework suddenly dispels.

Schumann’s youthful performance vehicle exemplifies a style of piano music that contemporary writers often described as “brilliant” and that present-day scholars term “postclassical.”2 Soon after Hummel published the concerto in 1821, for example, a reviewer singled out both junctures as delightful and compelling. In the close of the exposition, he wrote, “fast parallel thirds create a highly brilliant image and plunge from the highest height of the soprano into the bass register with ecstatic speed.” When the solo embellishes the second theme, it “appears to the ear in an entirely new, interesting form.”3

Example 1.1. Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 85. Movement 1. Second theme and expositional close.

Schumann engaged with postclassical virtuosity throughout his compositions and reviews: in various cases, such virtuosity adopted, transformed, or pointedly diverged from postclassical idioms. One important thread in chapters 1 through 4 will track this engagement during the late 1820s and 1830s, when Schumann was mostly composing solo piano music. Schumann’s engagement with this style, moreover, extended across his career: the concertos we will encounter in chapters 5 and 6 also employ postclassical conventions.

Though postclassical piano showpieces displayed composers’ individual styles, they shared an approach to piano texture. In Jim Samson’s description:

Its basic ingredients included a bravura right-hand figuration that took its impetus from the light-actioned Viennese and German pianos of the late eighteenth century and a melodic idiom … that was rooted either in Italian opera, in folk music, or in popular genres.4

Showpieces like Hummel’s feature transparent, glittering textures that highlight the attack of each individual tone. They often embellish simple melodies or harmonic schemes with ornate detail. In sections of constant passagework—virtuosic variations, for example, or the closes of concerto expositions and recapitulations—figuration unfolds in rhythmically foursquare, consistent patterns. The “brilliant” sound emerges when strings of pristinely audible notes and patterns fly by at high velocity and in regular succession, especially when they course through the piano’s clarion upper octaves.5

Conventions other than texture shaped the way listeners encountered these sounds. The structures of postclassical concertos, for example, differed from those of Mozart and Beethoven, and the variation set and opera fantasy genres featured their own norms. Composers of postclassical showpieces also drew upon a conventional vocabulary of figurational patterns, musical topoi, and genre markers, some of which Samson has mapped: ideas based on scales, turns, double notes, and broken octaves, for example, and styles such as the march, prelude, pastoral, or bel canto aria.6

Postclassical virtuosity pervaded early and mid-nineteenth-century musical life. Compositions ranged from large-scale fantasies and concertos to compact etudes and rondos, and they graced the drawing rooms of amateur pianists as well as the concerts of professional virtuosos. The variation sets of Henri Herz, for example, consumed a large share of the Parisian sheet-music market and also appeared on Clara Wieck’s concerts from the late 1820s through the mid-1830s.7 Besides Herz and Hummel, composer-pianists who wrote in this tradition included Carl Czerny, Frédéric Kalkbrenner, Carl Maria von Weber, Franz Hünten, Theodore Döhler, and Henri Bertini. Postclassical virtuosity also informed early works by Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt, Sigismond Thalberg, and Ignaz Moscheles. Most of these composer-pianists had their heydays between the late 1810s and the 1830s (though some careers, like Herz’s, continued well beyond): Schumann himself wrote that Moscheles’s 1815 “Alexander” Variations evoked “a time when the word ‘brilliant’ gained momentum and legions of girls fell in love with Czerny.”8 Many composers of postclassical piano music were based in Vienna or Paris. The latter city, especially, offered a booming concert scene, a vibrant salon culture, and advantageous publishing opportunities. Star pianist-composers also trained in these cities, particularly at the Paris Conservatoire or in Carl Czerny’s Vienna studio. These virtuosos and their music also enjoyed international dissemination and popularity. Like the Franco-Italian operas whose themes they borrowed for fantasies and variations, their showpieces sold well and influenced composers throughout Europe and North America. Many virtuosos completed training or established credentials outside Vienna or Paris and only later went to these cities, some for the rest of their careers (Chopin, for example), some for extended stays (Schumann’s friend, the lesser-known virtuoso Ludwig Schuncke), and others for significant concert tours (Clara Wieck).

Schumann, who spent his career in Germany, was part of this cosmopolitan current. At the same time, he joined a generation of composers and performers who absorbed postclassical pianism but also developed strikingly original, idiosyncratic approaches to virtuosity that set them apart from their postclassical models and colleagues. For example, Liszt’s 1826 Étude en douze exercices—composed shortly after he completed studies with Czerny—features figuration typical of postclassical etude collections. In his 1837 Grandes études, he extensively reworked these early exercises to create less transparent effects: massive sonorities that push the piano to its limit, figuration that demands vertical, aggressive gestures, and climaxes that arise from accumulating layers of texture. Chopin complicated postclassical figuration with intricate counterpoint possibly influenced by his study of Bach.9 Though Thalberg’s early opera fantasies burst with brilliant passagework, his signature “three-handed technique” embeds melodies within wide-ranging arpeggios, blending individual notes into resonant waves of texture that sustain a sweeping melody. In his writings and compositions, Schumann also reimagined the sound of piano virtuosity and the kinds of listening experience it could offer.

![]()

1 Florestan among the Revelers: Postclassical Virtuosity and Schumann’s Critique of Pleasure

This chapter explores a debate that consumed Schumann as a critic during the 1830s and centered on popular, postclassical showpieces.1 Though the discussion raised issues of compositional style, its fundamental concerns were affect and listening experience: the pleasures these pieces offered the listener (or listening player). Schumann and many other commentators agreed that these showpieces were designed to stimulate unflagging delectation and engagement. Whether they were commending or critiquing, they usually described this pleasure as sensuous in effect, and they stressed that it was effortlessly accessible to perceive, produced no strain on the listener, and appealed regardless of one’s musical learnedness. “Accessible” here did not necessarily mean “easy to play”—the music required an advanced technique and, though writers did note when pieces were comfortable for the pianist, they emphasized the auditory experience. Throughout his reviews for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Schumann waged an elaborate critique of this pleasure. Particularly in writings on Herz, Kalkbrenner, Döhler, and Thalberg, Schumann painted the delights they generated as frivolous and superficial, as shallow pleasures lamentably unredeemed by transcendent, inner qualities.

On the other hand, some largely unexplored sources from two powerful writers on virtuosity delivered a spirited defense of this aesthetic of pleasure. Both provide an important context for Schumann’s critique: ideals and in some cases specific reviews to which he was responding. One was Gottfried Wilhelm Fink, editor of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung—the archrival of Schumann’s Neue Zeitschrift.2 Though the Zeitung was one of the most significant German-language music journals of its time, Fink’s work has attracted little scholarly attention, and studies that do exist emphasize his tolerant tone and pleas for artistic pluralism.3 Specifically exploring his discussions of pleasurable virtuosity, though, reveals his basic assumptions about virtuosity’s aesthetic and social significance. The other writer was Carl Czerny, who produced a massive oeuvre of showpieces and wrote several pedagogical treatises. Scholars have already mined Czerny’s writings for insight into compositional conventions and improvisation practices. My discussion here newly considers the effects that Czerny believed virtuosic improvisations and compositions should produce for the listener. It would be reductionist to treat Czerny’s treatises as a key to all postclassical pianism. However, he was an influential teacher whose students included Liszt, Thalberg, and Döhler. He also wrote about genres and composers Schumann knew and reviewed, offering analyses and viewpoints that clarify those we find in the Zeitschrift.

Schumann’s critique of pleasure became a central point of contention in the skirmishes between the Neue Zeitschrift and the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung. Until Fink retired in 1841, one could read writers for the two papers sniping at one another in their essays. There were several causes for the rivalry. It started with personal enmity: when the Zeitung published Schumann’s “Ein Opus II” essay on Chopin in 1831, Schumann believed Fink had mishandled his review (see chapter 2). The rivalry also hinged on larger issues, including Fink’s relatively conservative perspective versus Schumann’s belief that his Davidsbund was rebelling against an ossified older order, Fink’s pragmatic, tolerant outlook versus Schumann’s belief that contemporary music journals were not exacting enough, and Fink’s critical stance toward what he called “Romanticism” versus Schumann’s embrace of it.4 In essays that described actual showpieces, though, both writers returned again and again to the issue of pleasure. Schumann or one of his reviewers would criticize a piece for primarily offering sensuous, pleasant experiences, and the Zeitung would retort that there was nothing wrong with that. In some cases, Fink argued that providing such experiences was in fact a laudable goal.

Schumann’s role in this debate reveals several new dimensions of his engagement with virtuosity. At the simplest level, it helps us revise the canonized view of his criticism. Even when scholars have refrained from explicitly endorsing Schumann’s judgments, they have often interpreted his writings as a quest for sheer musical quality. Leon Plantinga reveals the sophistication and nuance of Schumann’s writings, for example, but still characterizes the Zeitung–Zeitschrift rivalry as “a case of high standards versus no standards.” Similarly, Joachim Draheim has mapped Schumann’s wide-ranging responses to Herz but contends that his more exasperated reviews were attacking “dull musical substance that is in no way commensurate with the technical demands.”5 Schumann did pan music that he considered badly written or hackneyed. In fact, however, many of his writings on popular showpieces were responding to an aesthetic that other critics presented as wholesome, philosophically and practically justified, and a sign of good compositional craftsmanship. Schumann applied his critique even to music he considered effective and original.

These sources also help us ground our discussion of postclassical virtuosity and Schumann’s critique in the listening experience. Recent scholarship has often viewed the postclassical repertoire through an economic lens. Jim Samson notes, “This was music designed to be popular and happy to accept its commodity status,” Laure Schnapper has revealed the symbiotic relationship between the...