eBook - ePub

New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs

The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium

- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs

The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium

About this book

Easily distinguished by the horns and frills on their skulls, ceratopsians were one of the most successful of all dinosaurs. This volume presents a broad range of cutting-edge research on the functional biology, behavior, systematics, paleoecology, and paleogeography of the horned dinosaurs, and includes descriptions of newly identified species.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs by Michael J. Ryan,Brenda J. Chinnery-Allgeier,David A. Eberth,Brenda J. Chinnery–Allgeier, Patricia E. Ralrick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Evolution. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

OVERVIEW

1

Forty Years of Ceratophilia

With the death of my beloved and highly esteemed mentor John Ostrom (1928–2005), I seem to have become the dean, or at least the senior citizen, of ceratopsian studies. Of course my interest in dinosaurs came from my childhood in the 1950s, at a time when there was not nearly so much dinosaur “stuff.” A vivid early encounter with dinosaurs came when my mother, a lover of classical music, took me to see Walt Disney’s Fantasia. I was enthralled by the paleontology segment that started with the beginning of unicellular life in the primordial seas and ended with the death march of the dinosaurs to the stirring chords of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps. Growing up in South Bend, Indiana, we also visited the Field Museum in Chicago, where I remember the mummies but not the dinosaurs. I really liked the coal mine at the Museum of Science and Industry! My father, a professor of evolutionary biology, nourished me with Colbert’s (1951) The Dinosaur Book and Roy Chapman Andrews’s (1953) All About Dinosaurs. My early experiences were very important to my formation. In consequence I always consider it a privilege when children (of any age) visit my lab or when I am invited into an elementary school to share some of the excitement of my field with them. Who knows which of them will become one of the next generation of paleontologists? I corresponded briefly with a bright fifth-grader from rural New York State years ago, met him as a freshman at his college a decade later, supervised his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, and now enjoy his collegiality at the Carnegie Museum. Matt Lamanna is certainly living proof for the need to take children seriously!

My family moved to Aylmer, Québec, a suburb of Ottawa, Canada’s capital, when I was 11 years old. I lived at home and attended the University of Ottawa, where my father taught, enjoying the benefits of home cooking and free tuition. I date my own entry into the field of paleontology from 1968, the year of my graduation from university and my entry into graduate school at the University of Alberta. Thus my professional activities span parts of five decades and, God willing (shudder!), soon enough to be six decades. Moreover, my personal acquaintances in paleontology range not only to the beginning of the twentieth century in the persons of such luminaries as George Gaylord Simpson (b. 1902); E. H. Colbert (b. 1905); E. C. Olson (b. 1910), but back into the nineteenth century (A. S. Romer, b. 1894). These historical greats still attended Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual meetings when I began to attend, beginning in 1967. As a ceratophile (I seem to have coined this fairly obvious term, meaning “lover of horns,” and applied it in my book to Darren Tanke and myself [Dodson 1996: 180]), I am proudest of all to have known Charles M. Sternberg (1885–1981). He still came into the paleo labs of the National Museum of Canada once a week during the summer that I worked in the prep lab under the supervision of Dale Russell, my ever-ebullient mentor and friend. One of my great regrets is that I never took C. M.’s photograph. My sense of history was deficient in those days—only as I matured did I gain a proper sense of awe at the human dimension of discovery and scholarship. It is difficult to think of oneself as part of history. However, one can at least accept that each of us is part of a continuum. In an academic sense, I did not spring fresh from the brow of Job, but I am the product of my academic mentors, Dale Russell (National Museum of Canada—now the Canadian Museum of Nature), Richard C. Fox (University of Alberta), and John Ostrom (Yale University)—thanks, Dads! Through John Ostrom I can trace my lineage back through E. H. Colbert, to Henry Fairfield Osborn and W. K. Gregory, from the former to E. D. Cope, and then back to Joseph Leidy (1823–1891), who is revered as the father of American paleontology. Note that through my Yale and Philadelphia sojourns, there is an interesting blending of both the Marsh and Cope legacies!

I did not set out to become a student of horned dinosaurs. It just sort of happened. It was a quiet field when I entered it, and remained so for many years, but for the last decade and a half it has been very active. I majored in geology at the University of Ottawa, and although paleontology was part of the curriculum, I enjoyed sedimentology and geomorphology as well, and considered these fields for graduate work. I participated in fieldwork on Somerset Island in the Canadian Arctic in 1965 and 1966. Here I collected Silurian shelly invertebrates and Devonian ostracoderms and placoderms with David Dineley, as my introduction to field paleontology. In 1967, I spent a magical summer before my senior year in the ancient paleo laboratory at the National Museum of Canada. It was in this limestone block building at Sussex and Georgestreets where Lawrence Lambe began to put Canadian dinosaurs on the map in the early 1900s. Here I met C. M. Sternberg, a hoary link to a glorious past. He was old and stooped, but his eyes still sparkled. I also met Wann Langston, Jr., who spent a month there in his study of Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis. There Dale Russell became my mentor and friend. That summer Gilles Danis and Gerry FitzGerald began their careers in paleontology as well. This auspicious alignment of the planets, so to speak, confirmed my desire to become a paleontologist. Initially I planned to go to Austin and do a master’s degree with Wann Langston at the University of Texas, but in 1968, the Vietnam War was raging, and it seemed to make a great deal of sense to remain in Canada for a while. Dale Russell encouraged me to apply to the University of Alberta to study with Richard C. Fox, which I did. Dale provided me with ideas both for my master’s research and my Ph.D. I spent the summer of 1968, 10 weeks of it, living in a tent at Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, with my new bride and field assistant, Dawn. Here I walked over the decaying remains of ceratopsians while collecting taphonomic data for my master’s thesis (Dodson 1971), but did not otherwise latch onto ceratopsians as the objects of my desire.

My first research encounter with ceratopsians arose when I went to Yale for my Ph.D. in 1970. It may be said that in those days dinosaur studies were in a “quiet” phase in the United States. Colbert had retired from the American Museum of Natural History and had moved to Flagstaff. It was only at Yale that dinosaur studies were being pursued with vigor by young John Ostrom, whose studies on hadrosaurs (Ostrom 1961, 1964a) and ceratopsians (1964b, 1966) certainly attracted my attention. John had just completed five years of fieldwork in the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of the Bighorn Basin, and in announcing the exciting discovery of the hot-blooded predator Deinonychus (Ostrom 1969) introduced an entire new dinosaur fauna including the basal iguanodontian, Tenontosaurus, the nodosaurid Sauropelta, and the problematic small theropod Microvenator (Ostrom 1970a). My arrival at Yale coincided with Ostrom’s rediscovery of a specimen of Archaeopteryx, the first new one to be recognized since 1877 (Ostrom 1970b). Unknown to me until my arrival in New Haven was a certain long-haired, bearded, and chromatically attired gentleman named Robert Bakker, who filled the air with colorful descriptions of warm-blooded dinosaurs. Bob was a stimulating friend and an important intellectual influence on me. These were exciting times at Yale. Jim Farlow arrived at Yale two years later, and he looms large in my early ceratopsian studies.

My work at Yale involved biometric studies of growth series of dinosaurs (Dodson 1974). Ostrom wisely counseled me to begin my work with alligators, to establish my knowledge of basic reptilian osteology, to hone my practical techniques of measurement with the tools of the trade, calipers and tape measure, and to get a handle on analytical techniques. Alligators are to paleontologists what Drosophila is to geneticists or Caenorhabditis elegans is to developmental biologists. I hesitate to admit just how primitive my analytical techniques were. I resisted acquiring competence with computers long past the point of reasonableness. This was, of course, long before the advent of desktop computing. The personal computer had not been developed (I acquired my first personal computer only in 1984, and it was unspeakably crude by today’s standards—word processing programs did not yet have spell checkers!).

The alligator study (Dodson 1975a) proved to be a very useful baseline, and it continues to be cited in a variety of contexts by paleontologists whom I admire, even in recent years (e.g., Houck et al. 1990; Clark et al. 2000; Brochu 2001; Erickson et al. 2003; Chinnery 2004; Farlow et al. 2005; Evans et al. 2005). I also published a study of two closely related species of Sceloporus lizards, based on a data set kindly provided by Ernest Lundelius (Dodson 1975b). This study provided a careful analysis of a data set that was complicated by both sex and taxonomy. The sexual difference was real but proved difficult to uncover. At last I was ready to take on dinosaurs in two conceptually related studies. The easier case was that of Protoceratops, the more difficult case that of Canadian lambeosaurine hadrosaurs.

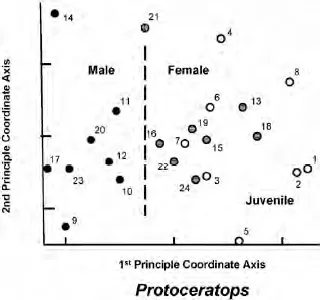

FIGURE 1.1. Principal coordinates analysis of a growth series of Protoceratops andrewsi showing juveniles (open circles), adult males (solid circles), and adult females (horizontal hatching). The identity of specimen 21 (vertical hatching) is ambiguous. Redrawn from Dodson (1976).

Protoceratops andrewsi is one of the great treasures of the American Museum of Natural History’s famed Central Asiatic Expedition of the 1920s, headed by the flamboyant Roy Chapman Andrews. Using the magnificent display skulls, I was ready to tackle growth in size from small specimens (basal length 76 mm) to large (basal length 357 mm). Using both bivariate plots and multivariate statistics (Fig. 1.1), I showed that there is a distinct dimorphism in the large specimens. One group of specimens showed an arch over the nose (site of the presumptive nose horn), broadly flaring jugals, and a broad and elevated frill. The second group consisted of specimens with less arching over the nose and with frills that were slightly lower and narrower (Fig. 1.2). The smaller specimens plotted with the latter group of large specimens. The dimorphism demands explanation, and no one has ever argued for two species for the specimens from Shabarak Usu (Lambert et al. 2001 recently named P. hellenikorhinus from Inner Mongolia). Accordingly, my interpretation is that the dimorphism is sexual in nature, and that males had the taller, wider, showier skulls. The crest of Protoceratops is eggshell thin, and fits well, in my judgment, the paradigm of a display structure rather than a mechanical framework for jaw muscles. Sexual dimorphism had been suggested before for Protoceratops, tentatively by Brown and Schlaikjer (1940), analytically by Kurzanov (1972), who had only seven skulls to work with; but my study (Dodson 1976) was the most rigorous mathematically and had the largest sample size and growth range. The specimens in my study also all came from the same Mongolian locality, the Flaming Cliffs of Bayn Zag.

Claims of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs are properly greeted with skepticism (e.g., Sampson and Ryan 1997; Padian et al. 2005). In order to sustain a strong claim for sexual dimorphism, a significant sample of specimens is required from the same locality (thus ruling out geographic or chronological complications), ideally spanning a significant size range so that ontogenetic variation can be accounted for. Rigorous morphometric analysis is also required. These exacting requirements have rarely been met in dinosaur studies. The case for sexual dimorphism in Protoceratops is arguably the best in all of dinosaur paleontology. My attempt to infer sexes in lambeosaurine hadrosaurs (Dodson 1975c) held up for 30 years, but fell apart two years ago, not because of a faulty morphometric analysis but because new stratigraphic evidence from the Dinosaur Park Formation carefully analyzed by David Evans and colleagues (2006) showed that my putative sexes of Corythosaurus are likely time-successive species. I was wrong (Dodson 2007)!

No study in science, and least of all in paleontology, is definitive, in the sense of constituting the final word on a subject. New methods and fresh minds bring new insights. For example, my use of multivariate statistics brought new insights into Protoceratops three decades ago. Inevitably, other researchers would eventually revisit the topic. Greg Erickson developed along with Tatiyana Tumanova (Erickson and Tumanova 2000) a technique named Developmental Mass Extrapolation (DME) that combines skeletochronology and mass estimates to produce a growth curve. DME was first applied to Psittacosaurus mongoliensis, providing important insight into its life history. Psittacosaurus shows growth rates ranging from 2.6 g to 12.5 g/day to a maximum calculated body size of about 20 kg at age 9 years. Similar statistics will soon be available for Protoceratops. Erickson has joined a consortium led by Peter Makovicky and including Rud Sadleir and Mark Norell, as well as myself (Makovicky et al. 2007). Preliminary reanalysis of my data failed to reveal the dimorphism that I claimed. However, by way of documentation, I still possess the computer printouts that I produced at the Yale Computer Center in 1973 (now I know why I never throw anything out!). It was in fact quite difficult for me to extract the dimorphism I reported in 1976. Even an analysis of series of alligators, crocodiles, and gharials failed to separate three genera of extant reptiles in a principal coordinates analysis until I used ratios rather than raw measurements, which have the effect of swamping out everything else i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- List of Reviewers

- Part One: Overview

- Part Two: Systematics and New Ceratopsians

- Part Three: Anatomy, Functional Biology, and Behavior

- Part Four: Horned Dinosaurs in Time and Space

- Part Five: History of Horned Dinosaur Collection

- Afterword

- Index