![]()

Gabrielle A. Berlinger

1 Searching for Home in the Ephemeral Architecture of the Sukkah

WHAT IS THE relationship between materiality and spirituality in Jewish life? When and how do material things and Jewish religious experience meet and affect one another? And to what end? These questions crystallized for me during a sixteen-month research project that combined my two fields of interest: ritual practice and vernacular architecture—the study of common structures and everyday landscapes. For a period of eight years that culminated in this project, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork around the ancient Jewish festival of Sukkot, an annual commemoration of the Israelites’ forty-year journey through the Sinai Desert after the exodus from Egypt. I chose to study this holiday because of the temporary constructions that characterize its religious observance—ritual shelters called sukkot (Hebrew: tabernacle; booth) (Fig. 1.1). For seven festival days each fall, observant Jews around the world design and build these outdoor ritual architectures that evoke a multiplicity of memories and meanings, primary among them the impermanent shelters that the ancient Israelites used during their search for the Promised Land.1 My study explored the role of material culture in the contexts of migration and religious expression.

What follows are four scenarios in which contemporary sukkah (singular of sukkot) builders and users express distinct and intentional notions of “home” through the material architecture of their sukkot. Because the sukkah is a structure symbolic of the domestic space, its material manifestation often communicates the builder’s notion of “home.” My documentation of current-day Sukkot observance in Bloomington, Indiana; Jerusalem, Israel; Brooklyn, New York; and Tel Aviv, Israel illustrates how Jews construct ritual structures that convey personal and collective histories, conditions, values, and beliefs. Significantly, however, each individual locates meaning in a different material element of the sukkah’s construction: the frame of the sukkah, the interior decoration, the roof covering, or the totality of the architecture. This diversity of interpretation of the ritual structure demonstrates the range of meaning attached to the materials of Jewish ritual practice. Such variation drives the theoretical and methodological approach to what Leonard Primiano calls “vernacular religion,” or “religion as it is lived: as human beings encounter, understand, interpret, and practice it” (Primiano 1995, 51). Rather than rely on the often hierarchical and reductive categories of “folk,” “popular,” “unofficial,” and “official” to describe religious practice, Primiano identifies “vernacular” as a term that effectively draws on the perspectives of religious and folklore studies to emphasize the personal and private, and the artistry and agency that characterize individual belief systems. Primiano’s theory and approach to “vernacular religion” inform my study of Sukkot observance as I examine the diverse contexts and expressions of Jewish belief.

FIGURE 1.1.

The sukkah (Hebrew: tabernacle; booth) is the ritual structure that observers of the annual Jewish festival of Sukkot build and use for the weeklong holiday. This typical sukkah was constructed using green plastic tarps as walls and palm tree branches as roof covering (South Tel Aviv, Israel, 2010).

As such, the following four interpretations of the sukkah’s material form communicate four notions of “home”: home as nation, home as ethnicity, home as the Divine, and home as a just society. As French philosopher Gaston Bachelard has observed, “the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace” (Bachelard 1994 [1958], 6). In the context of Sukkot, the dream to which Bachelard refers is the notion of “home” that each sukkah builder nurtures through her or his practice—an ideal state of consciousness in which thoughts, memories, and hopes come together.

The written origins of Sukkot observance appear in Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible, where in verse 23:42–43, God commands Moses, “You shall dwell in booths for seven days. All native Israelites shall dwell in booths, that your generations may know that I made the people of Israel dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt” (ESV). Throughout history, religious, academic, and legal authorities have produced lengthy interpretations of this brief commandment that prescribes the observance of Sukkot. The essential requirements of sukkah construction, however, are few. According to halakha (Hebrew: Jewish religious law), first, the sukkah must have at least two full walls that are connected to each other, and a third wall at least one tefach (Hebrew: handbreadth) wide; and, second, the schach (Hebrew: roof covering) must be made of organic matter gathered from the earth (Fig. 1.2). No prescriptions about decoration of the sukkah exist in the original commandment (Fig. 1.3). Observant Jews pray, eat, socialize, and even sleep inside these structures for the week of the holiday, recalling the Israelites’ historic search for home and homeland, and raising consciousness about such concepts as human survival, connection to nature, homelessness and home, exclusion and belonging, and materiality and spirituality.

In this study of sukkah construction as an expression of “home,” the notion of belonging resonates with particular significance. First, one must know that the practice of hospitality lies at the heart of Sukkot observance, performed in the custom of welcoming outsiders into one’s sukkah for food, drink, and rest for the duration of the festival. Observers of this custom frequently recall the biblical story of Abraham welcoming three strangers into his tent (Genesis 18) as the model for their generosity. In return for his kind gesture, Abraham’s unexpected guests reveal to him that he and his wife will soon expect a child. Hospitality to strangers, it is believed, opens a door to unknown fortune. As one sukkah builder explained to me, “God loves hospitality. Abraham our Father searched for guests to host, for God said first you will respect hospitality, then you will respect me. God loves a person who welcomes guests into his home.” Hospitality grounds social behavior for the week of Sukkot, both affirming and challenging presumed positions of “insider” and “outsider.” As a temporary ritual structure defined by its “moment in and out of time,” the sukkah creates a space of inclusivity, a liminality that suspends ordinary boundaries and beliefs about belonging until the holiday ends (Turner 1969, 96). In this way, the commandment to welcome the stranger erases the division between outsider and insider and affirms the fact of belonging.

FIGURE 1.2.

Two biblical prescriptions determine the construction of a sukkah: it must have at least two full walls that are connected to each other and a third wall at least one handbreadth wide; the roof covering must be made of organic matter gathered from the earth (South Tel Aviv, Israel, 2010).

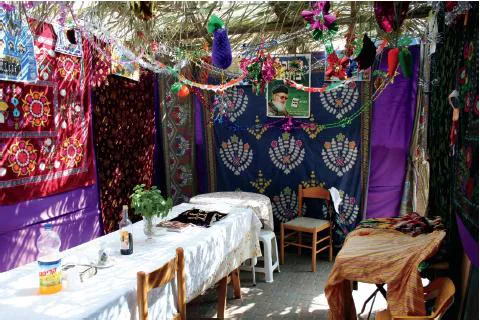

FIGURE 1.3.

Although no prescriptions about decoration of the sukkah exist in the original biblical commandment, many individuals aesthetically customize the sukkah’s interior to reflect personal values and cultural conditions. This sukkah, decorated with tapestries, photographs, and hanging tinsel chains, was built by a Bukharan Jewish family from Uzbekistan (South Tel Aviv, Israel, 2010).

Given this custom of hospitality in the context of Sukkot, the notion of belonging is particularly heightened in the Jewish Diaspora. Historically, the Jewish Diaspora refers to the “global ‘scattering’ of the Jewish people that took place in the years following the Babylonian captivity (sixth century BCE) and especially after the destruction of the temple by the Romans in 70 CE”—a fact that has engendered a “Jewish self-understanding of collective peoplehood in exile” (Jackson 2006, 18–19). The consciousness of this condition was perceptible in my focus on Sukkot ritual performance, whether in a sparse Jewish population of a small, midwestern American city, a dense, multicultural population of Jewish immigrants in an Israeli city, or an insular Orthodox Jewish population in a large East Coast American city. In these contrasting social environments, discussions about builders’ choices regarding sukkah construction and decoration revealed the interlocking local, national, and international networks to which they felt they belonged. American Jews in the Midwest might decorate their sukkah with an Israeli flag to express a relationship with Israel, and beside it, a treasured Wedgwood plate passed down in their family. Bukharan Jews who emigrated from Uzbekistan to Israel might hang a picture of an Uzbeki politician whom they still support alongside fresh pomegranates and dates, two of the “Seven Species” connected to the Land of Israel in the Hebrew Bible. And American Jews in the Northeast might attach laminated drawings of the Western Wall in Jerusalem to the sukkah’s interior while dangling above them are tinsel decorations and strings of light purchased in the “Christmas decoration” aisle at the local craft supply store. For Jews who perceive themselves as part of the Diaspora, such material interventions in the space of the sukkah express distinct senses of belonging—in this case, to American, Bukharan, and Israeli cultures. The diverse materiality in the sukkah tradition thus offers salient examples of “insider”-“outsider” identification, weaving together near and distant societies and landscapes. As Jason Baird Jackson has observed, “the artistic, expressive, and customary practices of globally dispersed populations—which often take on the privileged and self-conscious status of ‘heritage’—are central to the establishment and maintenance of a diasporic identity” (Jackson 2006, 19). The particular material traditions of sukkah construction and decoration illustrate how this expression of Jewish “heritage” helps to define a diasporic identity in which a sense of belonging is achieved through a nuanced, individual orientation of the “Self” to the “Other.”2

This wish for belonging that resonates with Sukkot observance is heightened in a second way in the context of the Jewish Diaspora—this time, through the observers’ reflection on attaining a just society. During the week of Sukkot, observers move out of their permanent homes to dwell outdoors, in impermanent shelters. One sukkah builder interpreted for me the significance of placing the sukkah outside: “The sukkah is a space of meeting. It’s supposed to be a way to be together, in solidarity and partnership, before the arrival,” he said, referring to the journey to the Promised Land in the biblical narrative. For him, the neutral space of the outdoor sukkah was a place to pause and be together, a moment to cross social and physical boundaries. The ritual of hosting and being hosted in the sukkah prompted this builder each year to reconsider his own boundaries, and to open his home and heart to unfamiliarity and difference. “It’s not the idea of v’ahavta l’reaacha camocha (‘Love your neighbor as you love yourself’), which is very important in and of itself,” he continued, “but how do people on a long journey in the desert arrive in a new land and all live together? How do people of different cultures come together to create one society?” The temporary sukkah has the power to bridge differences by allowing for reflection on how to live with each other, in fairness and in peace. Interpreting the space of the sukkah as a biblical moment of potential that preceded the Israelites’ arrival in the Promised Land, this builder reflected deeply on how to create a society of equals today.

Sukkot, a holiday that recalls the shelter provided in the desert during the Israelites’ search for “home,” holds at its core the yearning to belong, and the acceptance of others as equals. The following four case studies illustrate how individuals both in the “Diaspora” and in the “Promised Land” manifest their particular ways of belonging through the construction of “home.”

Contemporary Practice

My fieldwork journey begins in Bloomington, Indiana, a midwestern university town, in 2007. There, we meet Bakol Geller, an actress and teacher who grew up in Canada and lived in Israel before moving to Indiana. Bakol experienced little formal Jewish practice growing up and attended both the Jewish renewal and conservative services at Bloomington’s synagogue, explaining that she moved between categories of denominational affiliation as they fit her practice, which she described as “eclectic Judaism.”

Using the back of her house to support one of the walls of her sukkah, Bakol built her structure, paradoxically, by her clear blue swimming pool (Figs. 1.4, 1.5). The frame of her sukkah is built out of purchased lumber, metal brackets, green tarps, and gathered brush reused each year (except for the brush). In her construction, Bakol adheres to halakhic prescriptions and explains her strict observance as a way of connecting with “something bigger” than her own life experience: “It’s very real to me that even when I’m gone,...