- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Hurdy-Gurdy in Eighteenth-Century France

About this book

The hurdy-gurdy, or vielle, has been part of European musical life since the eleventh century. In eighteenth-century France, improvements in its sound and appearance led to its use in chamber ensembles. This new and expanded edition of The Hurdy-Gurdy in Eighteenth-Century France offers the definitive introduction to the classic stringed instrument. Robert A. Green discusses the techniques of playing the hurdy-gurdy and the interpretation of its music, based on existing methods and on his own experience as a performer. The list of extant music includes new pieces discovered within the last decade and provides new historical context for the instrument and its role in eighteenth-century French culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hurdy-Gurdy in Eighteenth-Century France by Robert A. Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

TERMINOLOGY

The English term hurdy-gurdy is used to describe two different instruments. First, there is the mechanical organ with a mechanism much akin to that of a player piano that was played earlier in this century by immigrants who begged for money with monkeys and tin cups on the street corners of American cities. These instruments are still found in European parks and on street corners and are differentiated from the hurdy-gurdy by other names, such as orgue de Barbarie in French. For many, the term hurdy-gurdy first calls to mind this instrument.

Much less familiar is the instrument whose sound is produced by a rosin-coated wheel, turned by a crank, that, like a bow, rubs against several strings. Some of these strings function as melody strings, others as drones, giving the instrument a sound like that of a bagpipe. This instrument is found throughout continental Europe as far east as western Russia and may be the only instrument truly indigenous to that continent. It has a history which goes back to the eleventh century. In different times and in different regions, it has taken many shapes and been given different names. All European languages, however, with the exception of English, differentiate between the mechanical organ and the bowed instrument. No other language or group of people draws parallels between these two instruments.

The following discussion centers around the bowed instrument as it appeared and was used in eighteenth-century France. It is therefore appropriate to refer to it by the name by which it was known in that time and in that place: the vielle.

SOCIAL LIFE IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

No musical instrument has suffered so grievously from changes in social status as the vielle. In eleventh-century Germany the vielle was associated with church music.1 By the twelfth century it was associated with music performed in the courts of the nobility. By the fourteenth century it had become associated with the lower classes and, eventually, by the fifteenth century, it became associated with blind beggars. Blindness was regarded as a physical manifestation of inner or moral blindness, and, therefore, the very appearance of the instrument in a painting suggested sin.2 Although certain painters at the beginning of the seventeenth century, such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) and Georges de la Tour (1593–1652), began to regard blind vielle players as victims of a tragic infirmity, the instrument retained a repellent reputation.

The views toward blind beggars and their instruments are reflected in the introduction to Marin Mersenne’s oft-quoted description of the vielle in Harmonie universelle of 1636.

If men of rank played the vielle as a rule, it would not be regarded with such contempt. But because it is played only by the poor, and particularly by blind men who earn their living from this instrument, it is held in less esteem than others, but then it is not as pleasing. This does not stand in the way of what I will explain here, since science belongs to both rich and poor, and there is nothing so low and vile in nature that it not be worthy of discussion.3

Social attitudes toward the instrument in the early part of the seventeenth century based on Mersenne and other writers have been discussed in detail.4 A number of civil documents surviving from the seventeenth century and published in secondary sources indicate that however poor players of the vielle in the first part of the seventeenth century may have been, they often had families and a place to live and legalized the events of their lives, such as births, deaths, and marriages, as did every other citizen.5 Documents indicate that at least some players took musician-apprentices, as did other musicians of the period. Some were members of the Corporation St. Julien-des-Ménétriers so viciously satirized by François Couperin (1668–1733) in his piece Les Fastes de la grande et anciénne Mxnxstrxndxsx from Book II (1716–1717). The “Seconde Acte” of this piece, titled “Les Viéleux et les gueux” (The vielle players and the beggars), consists of two “airs de viéle.” The piece accurately reflects the sound of the vielle with its c-g drones; however, the satirical element must be taken with a grain of salt. The music limps along, evoking the decrepit condition of those who played the instrument. Couperin devoted much effort to gaining a noble title, and his desire to separate himself from the lowly status associated with professional musicians during this era must be borne in mind.

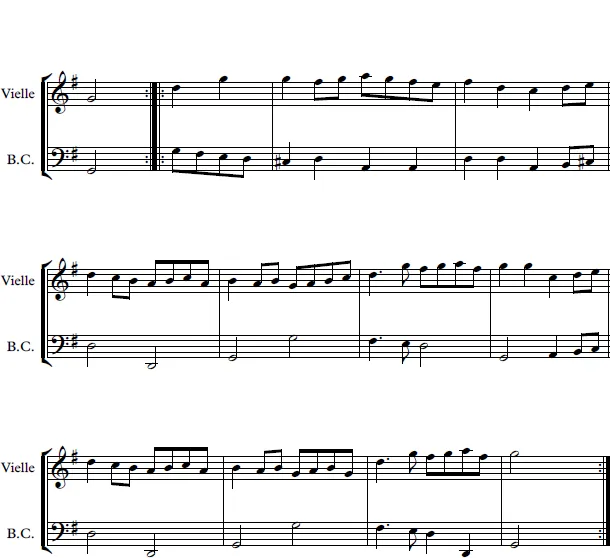

The first documented appearance of the vielle at the French court is in Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Ballet de l’impatience, presented at the Louvre on February 19, 1661. The “Third Entrée” of Part IV (LWV 14/47–50) begins with an instrumental introduction for the entrance of blind beggars. This is followed by an instrumental section labeled “ten blind men impatient of losing time for earning a living.” A récit follows, which in mock solemnity compares the unfortunate situation of the blind men with love that can be as blind as they are. The blind men then play an air on the vielle. The music contrasts with what precedes and follows in its diatonic and harmonically static nature: it is clearly composed with drones in mind. This piece would have been performed with the vielles doubling the violins on the top line of the five-part string ensemble (see example 1.1).

Example 1.1. Jean-Baptiste Lully, Ballet de l’impatience (LWV 14/50), “Second air pour les aveugles jouant de la vielle.” In this example the middle parts have been removed.

The vielle was further used in Lully’s Ballet des sept planètes, composed of ten entrées, a work that concluded the performance of Hercule amoureux (Ercole amante) by Francesco Cavalli on February 7, 1662. In Lully’s ballet a group of pilgrims are given a piece for vielles and ensemble (LWV 17/21). The use of the vielle in this work following so closely on the Ballet de l’impatience suggests that the instrument was regarded as a novelty, but using it twice seems to have been enough for Lully: he never composed music for it again.

Due to the paucity of sources dealing with the vielle in seventeenth-century France and its increasing use among the aristocracy, most writers have come to depend on the history of the vielle published by Antoine de Terrasson (1705–1782) in 1741.6 Terrasson republished his account in 1768, revealing his lifelong enthusiasm for the instrument.7 Terrasson was a musical amateur who played the musette, flute, and vielle, as well as a jurist and man of letters who was well equipped to argue a case. His purpose was to demonstrate that the vielle deserved respectability due to its antiquity. Tracing the origins of the instrument, he links it with ancient Greece and the lyre of Orpheus. While it is all too easy to attack the obvious inaccuracies in his discussion of Greek myths and music history, as other writers have done, it is well to remember that many instrumental treatises make a case for the importance of their subject by arguing that great age confers respectability.8 When Terrasson arrives at the period within living memory of the people around him, he demonstrates a profound understanding of the evolution of his instrument. Terrasson describes the arrival at court of two vielle players named “La Roze” and “Janot,” perhaps at the invitation of an enthusiastic courtier, sometime after the first operas of Lully had stimulated an interest in the instrument among the aristocracy.9 His discussion of the appearance of the vielle at court after 1671, possibly about 1680, appears to be based on testimony which can to some degree be corroborated from other sources.10

Throughout the seventeenth century the vielle shared its existence with the musette, a small bagpipe played by bellows pumped by the left elbow and requiring no breath from the player. This instrument had become fashionable with the upper classes in the early seventeenth century and continued to be popular until the end of the reign of Louis XV (about 1770), after which time it became extinct as a result of changing taste. This contrasts with the vielle, which has been played continuously until the present. The musette was cultivated by two families of professional players attached to the court musical establishment: the Hotteterres and the Chédevilles. It became an accepted orchestral instrument and has frequent, and sometimes extensive, parts in the great French operas of the early eighteenth century. Much of the music for the vielle can also be played on the musette and vice versa.

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

What is often overlooked in Mersenne’s discussion of the vielle in the Harmonie universelle is his speculation on how the vielle could be improved. This flexibility—the ability of makers to alter it to conform to changing musical styles and social function—has characterized the instrument since its origin and would be the basis for its growth in popularity throughout the eighteenth century.

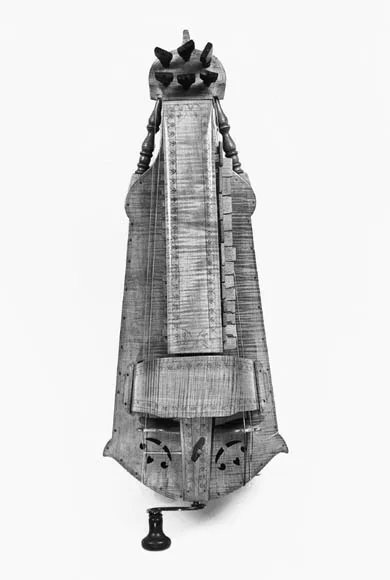

It seems likely that the vielle began its rise in society in the late seventeenth century with the development of a slightly more refined instrument that Terrasson refers to as a “vielle carrée”: a vielle with a characteristic shape generally described today as trapezoidal (see figure 1.1). This trapezoidal instrument was an attempt to reduce the size of the body while keeping the same string length.11 The three melody strings were tuned in D; one was an octave lower than the other two, with drones in D and A. Thus it was slightly larger than the vielle that later became standard in the eighteenth century (the melody strings of the latter were tuned to G). In spite of later innovations, this basic shape for the vielle continued to be used throughout the eighteenth century.12 It is pictured by Watteau in the second decade of the eighteenth century in the hands of gentlemen or idealized peasants in rustic settings.13 The instrument was most likely used at this time to play the bransles and other dances associated with the French countryside.

Figure 1.1. “Vielle carrée” after an instrument dated 1774. Copy by Thomas Norwood.

Example 1.2. Above and facing, Jean-Joseph Mouret, Le Philosophe trompé par la nature, “La Feste de village,” entrée.

Music created specifically for the vielle carrée is found in an opéra comique by Jean-Joseph Mouret (1682–1738), Le Philosophe trompé par la nature, presented at the Comédie de Saint Jory in 1725. In the final scene of this work, a group of grape harvesters (vendangeurs) make their entrance to the accompaniment of a vielle, bass viol, and continuo (example 1.2). They make light of the philosopher’s avoidance of the pleasures of life: their ignorance of Latin does not affect their enjoyment of eating, drinking, dancing, and making love. While the composer is not specific concerning the instrumentation of the following numbers, some would be appropriate for performance with vielle and others must have been performed on other instruments, since they make use of keys incompatible with the drones. This music is in A major and was composed for a vielle in D-A, probably the trapezoidal instrument. Presumably the presence of the vielle in this scene is justified by its rustic setting. However, the use of the vielle in the first number of Mouret’s opera is anything but rustic: it is treated in an expressive fashion not unlike any other melody instrument (example 1.1).

According to Terrasson, the seventeenth-century vielle was flawed by its unrefined melody strings, especially the heavy string at the lower octave. Further, the drone s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments for the Second Edition

- Introduction to the Second Edition

- 1 Historical Background

- 2 The Music

- 3 Musical Interpretation and Performance Practice

- 4 The Repertory

- 5 The Vielle in the Literature of Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France

- Appendix: Avertissements in the Works of Jean-Baptiste Dupuits

- Bibliography

- Index